HI 453 Interpretive Lectures

These followup lecture give you a brief "bird's eye view" of the

topic. Compare your interpretation of the documents with the thoughts

presented below. As you progress through the semester, you should be

able to formulate analyses closer to those of foreign policy experts.

US and Latin American Independence, 1810-26

[Flag of Haiti] The latter half of the eighteenth century witnessed an era of political revolutions

on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. First the upstart British colonists

of North America broke away from Great Britain in 1776. In 1789 the bloody French

Revolution broke out in the name of "liberty, equality, fraternity." Latin

America's first independence movement arose in France's Caribbean colony

of Haiti (Saint Domingue). There slaves, led by Toussaint L'Ouverture,

revolted against their masters on August 22, 1791. After more than a decade

of intense fighting, Haiti achieved and declared its independence in 1804. Recognizing the dangerous precedent of freed slaves ruling themselves, southern politicians in the US steadfastly refused to recognize the new black republic. The US government would not officially recognize Haiti as an independent nation until after the US Civil War had settled that divisive issue. Later Haiti's president Petion would play a major role in arming and supporting Simon Bolivar's efforts to liberate Venezuela. Meanwhile the United States, fearful of harming its commercial interests, would remain on the sidelines, turning aside repeated pleas for assistance from the leaders of Spanish American independence. [Flag of Haiti] The latter half of the eighteenth century witnessed an era of political revolutions

on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. First the upstart British colonists

of North America broke away from Great Britain in 1776. In 1789 the bloody French

Revolution broke out in the name of "liberty, equality, fraternity." Latin

America's first independence movement arose in France's Caribbean colony

of Haiti (Saint Domingue). There slaves, led by Toussaint L'Ouverture,

revolted against their masters on August 22, 1791. After more than a decade

of intense fighting, Haiti achieved and declared its independence in 1804. Recognizing the dangerous precedent of freed slaves ruling themselves, southern politicians in the US steadfastly refused to recognize the new black republic. The US government would not officially recognize Haiti as an independent nation until after the US Civil War had settled that divisive issue. Later Haiti's president Petion would play a major role in arming and supporting Simon Bolivar's efforts to liberate Venezuela. Meanwhile the United States, fearful of harming its commercial interests, would remain on the sidelines, turning aside repeated pleas for assistance from the leaders of Spanish American independence.

What gave rise to the push for Spanish American independence? The Spanish colonial system of the Habsburgs had declined sharply

and steadily over the years. In 1700 a new French dynasty, the Bourbons,

took over the Spanish throne and sought to reinvigorate the colonial economy.

They faced a formidable task. Mining revenues had declined as high grade

ores disappeared. Smuggling and piracy cut into royal revenues. Colonial officials often purchased their offices and

worked to recoup their investments as quickly as possible. Abuses of Indian

laborers and of African slaves abounded. Even the native-born white elite,

the criollos or creoles, faced discrimination at the hands of grasping

peninsular Spaniards. What did the empire look like? Here's a map of the political divisions of Spanish American empire in 1797. The sentiment for Latin American independence grew steadily with

the abuses of the colonial system. Trying to centralize colonial governance

and increase colonial revenues, the Bourbons instituted a wide-ranging series

of "Reforms." The Bourbon Kings sent new, powerful officials to Latin America. These intendants tried to increase tax revenues, enhance military defenses, promote trade, and bring improved technology to mining and agriculture. Fearing the power and wealth of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuit religious order), the Bourbons expelled them from the New World. Despite the strenuous efforts

of the Inquisition, books and ideas of the European Enlightenment spread

to Latin America. You should also examine the important impact that these

new ideas exerted on educated creoles in the New World. What gave rise to the push for Spanish American independence? The Spanish colonial system of the Habsburgs had declined sharply

and steadily over the years. In 1700 a new French dynasty, the Bourbons,

took over the Spanish throne and sought to reinvigorate the colonial economy.

They faced a formidable task. Mining revenues had declined as high grade

ores disappeared. Smuggling and piracy cut into royal revenues. Colonial officials often purchased their offices and

worked to recoup their investments as quickly as possible. Abuses of Indian

laborers and of African slaves abounded. Even the native-born white elite,

the criollos or creoles, faced discrimination at the hands of grasping

peninsular Spaniards. What did the empire look like? Here's a map of the political divisions of Spanish American empire in 1797. The sentiment for Latin American independence grew steadily with

the abuses of the colonial system. Trying to centralize colonial governance

and increase colonial revenues, the Bourbons instituted a wide-ranging series

of "Reforms." The Bourbon Kings sent new, powerful officials to Latin America. These intendants tried to increase tax revenues, enhance military defenses, promote trade, and bring improved technology to mining and agriculture. Fearing the power and wealth of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuit religious order), the Bourbons expelled them from the New World. Despite the strenuous efforts

of the Inquisition, books and ideas of the European Enlightenment spread

to Latin America. You should also examine the important impact that these

new ideas exerted on educated creoles in the New World.

[Flag of Venezuela] Creoles (persons of Spanish ancestry born in the New World) took the lead in moving Spanish America toward independence.

From Francisco Miranda and Simon Bolivar in Venzuela to Father Miguel Hidalgo

and Father Jos Maria Morelos (yes, a priest) in Mexico to Jose de San Martin in Argentina, able

leaders arose to lead the independence forces. In a famous "Letter from Jamaica," written in 1815, Simon Bolivar (1783-1830) vehemently expresesed the depth of patriot rejection of Spanish dominion. Spain had reconquered many of the colonies by that year, but Bolivar and other patriots would fight on to victory.

[Flag of Venezuela] Creoles (persons of Spanish ancestry born in the New World) took the lead in moving Spanish America toward independence.

From Francisco Miranda and Simon Bolivar in Venzuela to Father Miguel Hidalgo

and Father Jos Maria Morelos (yes, a priest) in Mexico to Jose de San Martin in Argentina, able

leaders arose to lead the independence forces. In a famous "Letter from Jamaica," written in 1815, Simon Bolivar (1783-1830) vehemently expresesed the depth of patriot rejection of Spanish dominion. Spain had reconquered many of the colonies by that year, but Bolivar and other patriots would fight on to victory.

The hatred that the Peninsula has inspired in us is greater than the ocean between us. It would be easier to have the two continents meet than to reconcile the spirits of the two countries. The habit of obedience, a community of interest, of understanding, of religion; mutual goodwill; a tender regard for the birthplace and good name of our forefathers; in short, all that gave rise to our hopes, came to us from Spain. As a result there was born a principle of affinity that seemed eternal, notwithstanding the misbehavior of our rulers which weakened that sympathy, or rather, that bond enforced by the domination of their rule. At present the contrary attitude persists: we are threatened with the fear of death, dishonor, and every harm; there is nothing we have not suffered at the hands of that unnatural step-mother--Spain. The veil has been torn asunder. We have already seen the light, and it is not our desire to be thrust back into darkness. Then chains have been broken; we have been freed, and now our enemies seek to enslave us anew. For this reason America fights desperately, and seldom has desperation failed to achieve victory.

The savage fighting raged

on from the initial declarations of independence in 1810 until the final battle of Ayacucho

in 1824. Finally freed of the Spanish yoke, the new creole leaders faced an equally difficult problem--how to govern their newly independent republics.

[The following section comes from my forthcoming biography of the Venezuelan independence leader Simon Bolivar.]

The United States, for reasons of self-interest, remained largely aloof from Spanish America's struggle against their Spanish masters. The one bright spot for Venezuelan efforts in the United States came from the skilled propagandist Manuel Torres. In October 1814, William Duane, publisher of the Philadelphia Aurora, provided Torres with letters of introduction to prominent politicians, including Secretary of State James Monroe. Duane described Torres as "a man of practical experience and [of] principles and views perfectly in the Sprit of our Government." Indeed, Torres activities attracted royalist attention to the point that they attempted to assassinate the Venezuelan. With his publications and personal meetings, Torres kept the patriot cause before the American people.

Pushed by propagandists like Torres and its own economic interests, the United States did not ignore events in South America. The State Department dispatched a number of special agents to the region to monitor events. Those serving in Gran Colombia from 1816 to 1818 included Christopher Hughes, Charles Morris, Baptis Irvine, a journalist of considerable experience, Joseph Devereux, and Commodore Oliver H. Perry, hero of the Battle of Lake Erie. Irvine, sent in early 1818 to demand indemnity for two American vessels seized and sold, failed in his mission. Perry made better headway, but he contracted yellow fever while descending the Orinoco River and died at Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, on August 23, 1819. Perhaps owing to George Washington's warning against foreign intrigues, the United States posture ranged from neutral to aloof concerning the travails of its South American neighbors.

The patriot cause also attracted a new champion in the United States, fiery Senator Henry Clay (1777-1852). A Virginia native, Clay entered the Senate in 1806 representing Kentucky. He had publicly expressed support for Spanish American independence as early January 1813, but the War of 1812 hamstrung American policy toward its southern neighbors for several years. Indeed, Bolivar recognized the deleterious impact of the conflict between Great Britain and the United States. The latter, "which, through her commerce, could have supplied us with war materials, did not do so because of her war with Great Britain. Otherwise, Venezuela could have triumphed by herself, and South America would not have been laid waste by Spanish cruelty and ruined by revolutionary anarchy."

In January 1816, Clay asked Congress "how far it may be proper to aid the people of South America in regards to the establishment of their independence." He supported a strong military for the United States, "if necessary, to aid in the cause of liberty in South America." He urged creation of an "American system" of republics to counter threats from Europe's Holy Alliance. He also anticipated the spirit of the Monroe Doctrine (1823) by asserting that "I consider the release of any part of American from the dominion of the Old World as adding to the general security of the New." Like many others, Clay considered expanding American commerce and blunting European influence in the Caribbean as important foreign policy goals. Although he had little concrete knowledge of events in Spanish America, Clay espoused views that would become official policy within a decade.

On March 24, 1818, Henry Clay requested that Congress appropriate $18,000 to send a minister to the provinces of the Rio de la Plata. A month later, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams made clear the conditions under which the United States would recognize a new Spanish American republic: "It is the stage when independence is established as a matter of fact so as to leave the changes of the opposite party to recover their dominion utterly desperate." Obviously, with the series patriot setbacks of the year, Bolivar could not expect recognition from the hemisphere's first republic.

As Bolivar faced serious military challenges in South America, the diplomatic front brightened in North America, where United States President James Monroe cautiously moved his nation beyond its longstanding neutrality. On March 8, 1822, he declared to Congress that five colonies, Colombia, Chile, Peru, Buenos Aires, and Mexico, should be recognized as independent nations. He further asked for money to deploy diplomatic missions to the new countries. After spirited debate Congress agreed, and Monroe signed the resulting legislation on May 4. The same month Adams informed Colombia's charge d'affaires Manuel Torres that Monroe would receive him. Although seriously ill, Torres traveled to Washington, DC, and met with Monroe on June 18. The United States thus became the first country outside of Latin America to recognize a new Spanish American republic. The Portuguese monarch, operating from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, had recognized Buenos Aires as independent in 1821. Despite appearing more overtly sympathetic, Great Britain would not publicly announce recognition any of the new republics until early 1825.

The United States finally appeared to be coming from the aid of the patriot cause when President James Monroe (1758-1831) delivered his seventh annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823. Embedded in his remarks, crafted with assistance from Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, emerged ideas that would have long-lasting impact on relations between the United States and Latin America. Recognizing the imminent end of Spanish colonialism in Latin America, the "Monroe Doctrine" asserted that the newly independent nations should "henceforth not be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers." The American president drew a sharp line between Old World monarchy and New World republicanism. Monroe then linked the destinies of North and South America: "we should consider any attempt on their part [Europe, including Russia] to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety." With a few cogent paragraphs, Monroe seemingly served warning to the Holy Alliance that America, North and South, was and would remain in the control of Americans.

Most European powers dismissed the bluster of the upstart republic, but some American politicians wanted to give the doctrine teeth. On January 20, 1824, the ever energetic Henry Clay asked Congress to go on record "that the people of these United States would not see, without serious inquietude, any forcible interposition by the Allied Powers of Europe in behalf of Spain, to reduce to their former subjection those parts of the continent of America which have proclaimed and established for themselves, respectively, independent Governments, and which have been solemnly recognized by the United States." Clay's resolution died of neglect, tabled and ignored for seven months, a harbinger of the direction of American policy. The Senate never considered the resolution at all.

Many Latin American leaders welcomed the belated expression of support from the north. Vice President Santander termed the message "an act worthy of the classic land of liberty" which "might secure to Colombia a powerful ally in case her independence and liberty should be menaced by the allied powers." Furthermore, on December 12, 1823, American minister Richard C. Anderson had arrived in Bogota. The Gaceta de Colombia warmly greeted his arrival that "cannot fail to inspire the most pleasing sensations in the bosom of every friend of liberty." Adams, however, quickly quashed such optimism. Seven months after Monroe's speech, Colombian Minister to the United States, Jose Maria Salazar, expressed pleasure "that the government of the United States has undertaken to oppose the policy and the ulterior designs of the Holy Alliance." He then asked, rather pointedly, "in what manner the government of the United States intends to resist any interference of the Holy Alliance," and would the United States "enter into a treaty of alliance with her [Colombia] to save America from the calamities of a despotic system."

On August 6, 1824, Monroe dashed Colombia's hopes for such an alliance and revealed the Monroe Doctrine as more rhetorical than substantive. "By the constitution of the United States, the ultimate decision of this question belongs to the Legislative Department of the Government." Adams reaffirmed that the United States would retain its traditional stance of neutrality and that it "could not undertake resistant to them [the Holy Alliance] by force of Arms." So much for help from the sister republic to the north. Writing to Santander on March 8, 1825, Bolivar recognized the disjuncture between words and actions and reflected acidly: "The English and the [North] Americans are only possible future allies, and they have their own selfish interests."

Bereft of meaningful assistance from the United States, the patriot forces pressed on to ultimately defeat Spain's forces and gain independence.

The savage fighting raged

on from the initial declarations of independence in 1810 until the final battle of Ayacucho

in 1824. Finally freed of the Spanish yoke, the new creole leaders faced an equally difficult problem--how to govern their newly independent republics.

[The following section comes from my forthcoming biography of the Venezuelan independence leader Simon Bolivar.]

The United States, for reasons of self-interest, remained largely aloof from Spanish America's struggle against their Spanish masters. The one bright spot for Venezuelan efforts in the United States came from the skilled propagandist Manuel Torres. In October 1814, William Duane, publisher of the Philadelphia Aurora, provided Torres with letters of introduction to prominent politicians, including Secretary of State James Monroe. Duane described Torres as "a man of practical experience and [of] principles and views perfectly in the Sprit of our Government." Indeed, Torres activities attracted royalist attention to the point that they attempted to assassinate the Venezuelan. With his publications and personal meetings, Torres kept the patriot cause before the American people.

Pushed by propagandists like Torres and its own economic interests, the United States did not ignore events in South America. The State Department dispatched a number of special agents to the region to monitor events. Those serving in Gran Colombia from 1816 to 1818 included Christopher Hughes, Charles Morris, Baptis Irvine, a journalist of considerable experience, Joseph Devereux, and Commodore Oliver H. Perry, hero of the Battle of Lake Erie. Irvine, sent in early 1818 to demand indemnity for two American vessels seized and sold, failed in his mission. Perry made better headway, but he contracted yellow fever while descending the Orinoco River and died at Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, on August 23, 1819. Perhaps owing to George Washington's warning against foreign intrigues, the United States posture ranged from neutral to aloof concerning the travails of its South American neighbors.

The patriot cause also attracted a new champion in the United States, fiery Senator Henry Clay (1777-1852). A Virginia native, Clay entered the Senate in 1806 representing Kentucky. He had publicly expressed support for Spanish American independence as early January 1813, but the War of 1812 hamstrung American policy toward its southern neighbors for several years. Indeed, Bolivar recognized the deleterious impact of the conflict between Great Britain and the United States. The latter, "which, through her commerce, could have supplied us with war materials, did not do so because of her war with Great Britain. Otherwise, Venezuela could have triumphed by herself, and South America would not have been laid waste by Spanish cruelty and ruined by revolutionary anarchy."

In January 1816, Clay asked Congress "how far it may be proper to aid the people of South America in regards to the establishment of their independence." He supported a strong military for the United States, "if necessary, to aid in the cause of liberty in South America." He urged creation of an "American system" of republics to counter threats from Europe's Holy Alliance. He also anticipated the spirit of the Monroe Doctrine (1823) by asserting that "I consider the release of any part of American from the dominion of the Old World as adding to the general security of the New." Like many others, Clay considered expanding American commerce and blunting European influence in the Caribbean as important foreign policy goals. Although he had little concrete knowledge of events in Spanish America, Clay espoused views that would become official policy within a decade.

On March 24, 1818, Henry Clay requested that Congress appropriate $18,000 to send a minister to the provinces of the Rio de la Plata. A month later, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams made clear the conditions under which the United States would recognize a new Spanish American republic: "It is the stage when independence is established as a matter of fact so as to leave the changes of the opposite party to recover their dominion utterly desperate." Obviously, with the series patriot setbacks of the year, Bolivar could not expect recognition from the hemisphere's first republic.

As Bolivar faced serious military challenges in South America, the diplomatic front brightened in North America, where United States President James Monroe cautiously moved his nation beyond its longstanding neutrality. On March 8, 1822, he declared to Congress that five colonies, Colombia, Chile, Peru, Buenos Aires, and Mexico, should be recognized as independent nations. He further asked for money to deploy diplomatic missions to the new countries. After spirited debate Congress agreed, and Monroe signed the resulting legislation on May 4. The same month Adams informed Colombia's charge d'affaires Manuel Torres that Monroe would receive him. Although seriously ill, Torres traveled to Washington, DC, and met with Monroe on June 18. The United States thus became the first country outside of Latin America to recognize a new Spanish American republic. The Portuguese monarch, operating from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, had recognized Buenos Aires as independent in 1821. Despite appearing more overtly sympathetic, Great Britain would not publicly announce recognition any of the new republics until early 1825.

The United States finally appeared to be coming from the aid of the patriot cause when President James Monroe (1758-1831) delivered his seventh annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823. Embedded in his remarks, crafted with assistance from Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, emerged ideas that would have long-lasting impact on relations between the United States and Latin America. Recognizing the imminent end of Spanish colonialism in Latin America, the "Monroe Doctrine" asserted that the newly independent nations should "henceforth not be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers." The American president drew a sharp line between Old World monarchy and New World republicanism. Monroe then linked the destinies of North and South America: "we should consider any attempt on their part [Europe, including Russia] to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety." With a few cogent paragraphs, Monroe seemingly served warning to the Holy Alliance that America, North and South, was and would remain in the control of Americans.

Most European powers dismissed the bluster of the upstart republic, but some American politicians wanted to give the doctrine teeth. On January 20, 1824, the ever energetic Henry Clay asked Congress to go on record "that the people of these United States would not see, without serious inquietude, any forcible interposition by the Allied Powers of Europe in behalf of Spain, to reduce to their former subjection those parts of the continent of America which have proclaimed and established for themselves, respectively, independent Governments, and which have been solemnly recognized by the United States." Clay's resolution died of neglect, tabled and ignored for seven months, a harbinger of the direction of American policy. The Senate never considered the resolution at all.

Many Latin American leaders welcomed the belated expression of support from the north. Vice President Santander termed the message "an act worthy of the classic land of liberty" which "might secure to Colombia a powerful ally in case her independence and liberty should be menaced by the allied powers." Furthermore, on December 12, 1823, American minister Richard C. Anderson had arrived in Bogota. The Gaceta de Colombia warmly greeted his arrival that "cannot fail to inspire the most pleasing sensations in the bosom of every friend of liberty." Adams, however, quickly quashed such optimism. Seven months after Monroe's speech, Colombian Minister to the United States, Jose Maria Salazar, expressed pleasure "that the government of the United States has undertaken to oppose the policy and the ulterior designs of the Holy Alliance." He then asked, rather pointedly, "in what manner the government of the United States intends to resist any interference of the Holy Alliance," and would the United States "enter into a treaty of alliance with her [Colombia] to save America from the calamities of a despotic system."

On August 6, 1824, Monroe dashed Colombia's hopes for such an alliance and revealed the Monroe Doctrine as more rhetorical than substantive. "By the constitution of the United States, the ultimate decision of this question belongs to the Legislative Department of the Government." Adams reaffirmed that the United States would retain its traditional stance of neutrality and that it "could not undertake resistant to them [the Holy Alliance] by force of Arms." So much for help from the sister republic to the north. Writing to Santander on March 8, 1825, Bolivar recognized the disjuncture between words and actions and reflected acidly: "The English and the [North] Americans are only possible future allies, and they have their own selfish interests."

Bereft of meaningful assistance from the United States, the patriot forces pressed on to ultimately defeat Spain's forces and gain independence.

19th Century: From Isolation to Expansion, 1820s-1850s

Fighting against the Spanish for independence had been a long, frustrating,

exhausting, and costly effort. Winning independence was difficult, but

creating a new nation proved equally challenging. The creole elite that

had led the independence movement agreed on only one point. THEY, the "gente

decente," (better people) should rule--not the illiterate, colored masses.

But what form of government should replace the old colonial system? How

should the economy function? These and other thorny questions faced the

creole elites during the difficult decade of the 1820s.

Simon Bolivar (1783-1830) labored mightily to resolve the political

dilemmas of Latin America. He called together a Congress in Panama in 1826

to try to get the new republics to cooperate. He failed. Indeed, he would

survive assassination attempts only to be hounded into exile four years

later. He died in Santa Marta, Colombia, too ill to leave the continent

he fought to free.

Bolivar summarized his suggestions for forming new national governments in an important speech to the Congress of Angostura (Colombia), delivered on February 15, 1819.

Although those people [North Americans], so lacking in many respects, are unique in the history of mankind, it is a marvel, I repeat, that so weak and

complicated a government as the federal system has managed to govern them in the difficult and trying circumstances of their past. [Notice the Liberator's obvious distaste for North Americans and their "weak and complicated" government.] But, regardless of the

effectiveness of this form of government with respect to North America, I must say that it has never for a moment entered my mind to compare the

position and character of two states as dissimilar as the English-American and the Spanish-American. Would it not be most difficult to apply to Spain

the English system of political, civil, and religious liberty: Hence, it would be even more difficult to adapt to Venezuela the laws of North America.

Nothing in our fundamental laws would have to be altered were we to adopt a legislative power similar to that held by the British Parliament. Like the

North Americans, we have divided national representation into two chambers: that of Representatives and the Senate. The first is very wisely

constituted. It enjoys all its proper functions, and it requires no essential revision, because the Constitution, in creating it, gave it the form and powers

which the people deemed necessary in order that they might be legally and properly represented. If the Senate were hereditary rather than elective, it

would, in my opinion, be the basis, the tie, the very soul of our republic. [Bolivar's distrust of the rule of the non-white masses comes through clearly here. By making the Senate an inherited position, the creole elite minority could maintain its powerful over time.]

Unfortunately, history would unfold in Latin America much as Bolivar warned in his last paragraph above. Historian E. Bradford Burns details many of the forces that destroyed any chance of democratic, stable governments in the newly independent Latin American nations. Just as not everyone agreed with Bolivar, not everyone agreed with

one another. Broadly speaking the creoles divided between liberal and conservative

elites.

In place of Simon

Bolivar's dream of a powerful "United States of Latin America," we find

a hodgepodge of small, often conflicting nations. Border disputes, such as that between Peru and Ecuador continue between many of these nations today. Of course the most costly border conflict would come at mid-century between the United States and Mexico. The latter country would lose half of its national territory.

Despite the warning by US President James Monroe (shown at left) in 1823, many foreign

nations intervened routinely in Latin America during the 19th century.

The Monroe Doctrine held little weight among the colonial European powers

of the time. Sometimes foreign intervention came about because of liberal-conservative

conflicts. A liberal government might repudiate the foreign loans taken

out by the preceding conservative regime. Bankers in Europe would entice

their governments to send gunboats in to collect on the debt. Mexico suffered

the gravest intervention when Louis Napoleon sent 30,000 French troops

to occupy the country from 1862 to 1867. Mexico defeated the French near Puebla on May 5th, 1862, (giving rise to the still-observed Cinco de Mayo celebrations), but the French eventually prevailed. (Puebla is about 60 miles southeast of Mexico City). Preoccupied with its own great

Civil War, the United States was in no condition to enforce the Monroe

Doctrine. As with internal political divisions, foreign intervention further

disrupted the political evolution of the new Latin American nations. Despite the warning by US President James Monroe (shown at left) in 1823, many foreign

nations intervened routinely in Latin America during the 19th century.

The Monroe Doctrine held little weight among the colonial European powers

of the time. Sometimes foreign intervention came about because of liberal-conservative

conflicts. A liberal government might repudiate the foreign loans taken

out by the preceding conservative regime. Bankers in Europe would entice

their governments to send gunboats in to collect on the debt. Mexico suffered

the gravest intervention when Louis Napoleon sent 30,000 French troops

to occupy the country from 1862 to 1867. Mexico defeated the French near Puebla on May 5th, 1862, (giving rise to the still-observed Cinco de Mayo celebrations), but the French eventually prevailed. (Puebla is about 60 miles southeast of Mexico City). Preoccupied with its own great

Civil War, the United States was in no condition to enforce the Monroe

Doctrine. As with internal political divisions, foreign intervention further

disrupted the political evolution of the new Latin American nations.

Latin American politics became more complex and complicated in the twentieth century. New political contenders, including women, the middle class, labor unions, and the military pressed their demands in the political arena. Another new political contender, and over time the most powerful, was the United States. During the twentieth century, the US must be considered part of the internal political struggles in Latin America. Its economic clout, political leadership, diplomatic wrangling, and propensity to military intervention made the US an integral part of Latin American politics.

=========== Latin Americans have long held ambivalent feelings toward the "Colossus of the North." Some independence leaders of the early nineteenth century looked to the then-new North American republic as a model and as a source of support for their efforts. The US did not assist in Latin American independence, and some leaders, such as Simon Bolivar, feared the materialism and expansionism of the United States. Writing to a friend on August 5, 1829, Bolivar lamented that the US seemed "destined by Province to plague [the rest of] America with torments in the name of freedom." In contrast, in a letter written on November 12, 1847 while visiting the US, Domingo F. Sarmiento, Argentina's future president, expressed admiration for North American democracy. He observed that even in the sparsely populated western frontier, "there is an appearance of perfect equality among the people in dress, manner, and even intelligence. The merchant, the doctor, the sheriff, and the farmer all look alike. . . . Gradations of civilization and wealth are not expressed, as among us, by special types of clothing. . . . They have no kings, nobles, privileged classes, men born to command, or human machines born to obey." With considerable prescience, however, Sarmiento identified the most glaring drawback of US society at the time. "Alas slavery, the deep, incurable sore that threatens gangrene to the robust body of the Union. . . ! A racial war of extermination will come within a century, or else a mean, black, backward nation will be found alongside a white one--the most powerful and cultivated on earth!" Indeed, in 1861, southerners would fire on Fort Sumter, SC, ushering in the bloody Civil War that would break out and tear the nation temporarily apart, just as the Argentine politician had warned.

=========== North Americans traveling to Latin America often expressed a sense of superiority and racism. The high point of American filibustering came with William Walker (1824-60), a Californian who first tried and failed to take Mexican Baja (Lower) California. In 1855, Walker took aim at Nicaragua, taking advantage of a civil war that divided the country. In May 1856

US President Franklin Pierce recognized the Walker regime.

After Walker had disrupted Central American politics and commerce for years, British and US investors tired of his escapades. Walker tried to seize control of the Accessory Transit Company (an American transport company in Nicaragua) from none other than business titan Cornelius

Vanderbilt. In response, Vanderbilt organized a coalition of Central American states to fight Walker. The dictator of Nicaragua surrendered on May 1, 1857, but thereafter tried tried twice more to retake Nicaragua. On his final, fateful attempt in 1860, British forces captured him on the coast of Honduras and then turned him over to officials in Honduras. They executed the freebooter on September 12, 1860. Nicaraguans still remember Walker as the first gringo imperialist to plague their nation.

=========== Walker well exemplified the racist attitudes of the time. He reestablished slavery in Nicaragua and made no apologies for taking power by invasion and force. "That which you ignorantly call 'Filibusterism' is not the offspring of hasty passion or ill-regulated desire; it is the fruit of the sure, unerring instincts which act in accordance with laws as old as the creation. They are but drivellers who speak of establishing fixed relations between the pure white American race, as it exists in the United States, and the mixed Hispano-Indian race, as it exists in Mexico and Central America, without the employment of force. The history of the world presents no such Utopian vision as that of an inferior race yielding meekly and peacefully to the controlling influence of a superior people. Whenever barbarism and civilization, or two distinct forms of civilization, meet face to face, the result must be war. Therefore, the struggle between the old and the new elements in Nicaraguan society was not passing or accidental, but natural and inevitable."

=========== Filibustering expeditions sought new lands. Many leaders of these expeditions desired to conquer new territory to be added to the US as future slave states to the Union. In 1849, for example, Narcisco Lopez initiated the first of three unsuccessful expeditions against Cuba. He convinced many prominent Southerners that the islanders wanted to revolt against Spain. In his final attempt in 1851, Lopez and his band of southern sympathizers landed in Havana. They expected the population would follow their lead and rise up against

Spain. (Ironically, the CIA "experts" who planned the doomed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1916 also assumed that the Cuban people would join the invading exile army and rise up against Fidel Castro. They, too, were wrong.) No popular acclaim greeted Lopez; instead Spanish military authorities executed him and 50 southerner supporters. It made little difference to Latin Americans that such freebooters operated without US government sanction. It seemed that "Yanqui" meddling would plague the region in a variety of forms.

Latin American politics became more complex and complicated in the twentieth century. New political contenders, including women, the middle class, labor unions, and the military pressed their demands in the political arena. Another new political contender, and over time the most powerful, was the United States. During the twentieth century, the US must be considered part of the internal political struggles in Latin America. Its economic clout, political leadership, diplomatic wrangling, and propensity to military intervention made the US an integral part of Latin American politics.

=========== Latin Americans have long held ambivalent feelings toward the "Colossus of the North." Some independence leaders of the early nineteenth century looked to the then-new North American republic as a model and as a source of support for their efforts. The US did not assist in Latin American independence, and some leaders, such as Simon Bolivar, feared the materialism and expansionism of the United States. Writing to a friend on August 5, 1829, Bolivar lamented that the US seemed "destined by Province to plague [the rest of] America with torments in the name of freedom." In contrast, in a letter written on November 12, 1847 while visiting the US, Domingo F. Sarmiento, Argentina's future president, expressed admiration for North American democracy. He observed that even in the sparsely populated western frontier, "there is an appearance of perfect equality among the people in dress, manner, and even intelligence. The merchant, the doctor, the sheriff, and the farmer all look alike. . . . Gradations of civilization and wealth are not expressed, as among us, by special types of clothing. . . . They have no kings, nobles, privileged classes, men born to command, or human machines born to obey." With considerable prescience, however, Sarmiento identified the most glaring drawback of US society at the time. "Alas slavery, the deep, incurable sore that threatens gangrene to the robust body of the Union. . . ! A racial war of extermination will come within a century, or else a mean, black, backward nation will be found alongside a white one--the most powerful and cultivated on earth!" Indeed, in 1861, southerners would fire on Fort Sumter, SC, ushering in the bloody Civil War that would break out and tear the nation temporarily apart, just as the Argentine politician had warned.

=========== North Americans traveling to Latin America often expressed a sense of superiority and racism. The high point of American filibustering came with William Walker (1824-60), a Californian who first tried and failed to take Mexican Baja (Lower) California. In 1855, Walker took aim at Nicaragua, taking advantage of a civil war that divided the country. In May 1856

US President Franklin Pierce recognized the Walker regime.

After Walker had disrupted Central American politics and commerce for years, British and US investors tired of his escapades. Walker tried to seize control of the Accessory Transit Company (an American transport company in Nicaragua) from none other than business titan Cornelius

Vanderbilt. In response, Vanderbilt organized a coalition of Central American states to fight Walker. The dictator of Nicaragua surrendered on May 1, 1857, but thereafter tried tried twice more to retake Nicaragua. On his final, fateful attempt in 1860, British forces captured him on the coast of Honduras and then turned him over to officials in Honduras. They executed the freebooter on September 12, 1860. Nicaraguans still remember Walker as the first gringo imperialist to plague their nation.

=========== Walker well exemplified the racist attitudes of the time. He reestablished slavery in Nicaragua and made no apologies for taking power by invasion and force. "That which you ignorantly call 'Filibusterism' is not the offspring of hasty passion or ill-regulated desire; it is the fruit of the sure, unerring instincts which act in accordance with laws as old as the creation. They are but drivellers who speak of establishing fixed relations between the pure white American race, as it exists in the United States, and the mixed Hispano-Indian race, as it exists in Mexico and Central America, without the employment of force. The history of the world presents no such Utopian vision as that of an inferior race yielding meekly and peacefully to the controlling influence of a superior people. Whenever barbarism and civilization, or two distinct forms of civilization, meet face to face, the result must be war. Therefore, the struggle between the old and the new elements in Nicaraguan society was not passing or accidental, but natural and inevitable."

=========== Filibustering expeditions sought new lands. Many leaders of these expeditions desired to conquer new territory to be added to the US as future slave states to the Union. In 1849, for example, Narcisco Lopez initiated the first of three unsuccessful expeditions against Cuba. He convinced many prominent Southerners that the islanders wanted to revolt against Spain. In his final attempt in 1851, Lopez and his band of southern sympathizers landed in Havana. They expected the population would follow their lead and rise up against

Spain. (Ironically, the CIA "experts" who planned the doomed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1916 also assumed that the Cuban people would join the invading exile army and rise up against Fidel Castro. They, too, were wrong.) No popular acclaim greeted Lopez; instead Spanish military authorities executed him and 50 southerner supporters. It made little difference to Latin Americans that such freebooters operated without US government sanction. It seemed that "Yanqui" meddling would plague the region in a variety of forms.

The Big Stick and Interventionism, 1898-1934

=========== Although US investment and influence had grown through the 19th century, European ties remained of greater importance for most Latin American nations. However, beginning in 1898, a few key events catapulted the US into a much greater role in the Latin American arena. Thanks to the War of 1898 [Spanish-American War], the US gained real estate in the Caribbean. We took over Puerto Rico from Spain. Historians debate the exact mix of causes for the war, but any short list certainly includes the following issues and events: =========== Although US investment and influence had grown through the 19th century, European ties remained of greater importance for most Latin American nations. However, beginning in 1898, a few key events catapulted the US into a much greater role in the Latin American arena. Thanks to the War of 1898 [Spanish-American War], the US gained real estate in the Caribbean. We took over Puerto Rico from Spain. Historians debate the exact mix of causes for the war, but any short list certainly includes the following issues and events:

- Yellow journalism: A century ago, major New York City newspapers behaved like the supermarket tabloids of today. Anything to sell papers--truth be damned. In particular William Randolph Hearst saw the great salability of the conflict in Cuba and played a leading role in fanning anti-Spanish sentiments.

- Black Legend: Reinforcing the lurid (sometimes true) stories coming out of Cuba, stood the centuries-old Black Legend. The origins date to the sixteenth-century conflicts between Roman Catholic Spain and Protestant England. English writers and politicians created a corpus of infamatory anti-Spanish writings and views. These views continued for centuries, providing "historical proof" that Spaniards had always been cruel, domineering, undemocratic, etc. etc. Cartoons showed General Weyler, in charge of Spanish forces in Cuba, as the last of the Spanish conquistadores.

- The De Lome Letter:

[In February of 1898, a Cuban agent in Havana stole a letter that had been written the preceding December by Spain's minister to the United States, Dupuy De Lome. It was printed in William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal, the most ardently pro-war newspaper in the United States. The letter helped to set the stage for the war fever that came with the sinking of the battleship Maine a short time later. The letter read in part. . . ]

Besides the ingrained and inevitable bluntness (groseria) with which is repeated all that the press and public opinion in Spain have said about Weyler, it once more shows what McKinley is, weak and a bidder for the admiration of the crowd, besides being a would-be politician (politicastro) who tries to leave a door open behind himself while keeping on good terms with the jingoes of his party.

Nevertheless, whether the practical results of it [the message] are to be injurious and adverse depends only upon ourselves. I am entirely of your opinions; without a military end of the matter nothing will be accomplished in Cuba, and without a military and political settlement there will always be the danger of encouragement being given to the insurgents by a part of the public opinion if not by the Government.... I do not think sufficient attention has been paid to the part England is playing.

It would be very advantageous to take up, even if only for effect, the question of commercial relations, and to have a man of some prominence sent hither in order that I may make use of him here to carry on a propaganda among the Senators and others in opposition to the junta and to try to win over the refugees.

- Explosion of the battleship Maine: This startling event "proved" the evil and perfidy of Spain. It gave President McKinley the tangible reason he needed to urge war with Spain. You'll find lots of related documents on the Primary Sources Page.

- Anti-colonialism, Monroe Doctrine: Many Americans believed that nations should

not hold colonies, a vestige of the past. Others believed that, according

to the Monroe Doctrine, the US should continue to oppose European meddling

in the Western Hemisphere. Ironically, the US initially insisted in

the that it had no designs on taking over real estate that once belonged

to Spain. With the Teller Amendment, the US

Congress expressly stated that the US had no interest in taking over

Cuba. That sentiment would change quickly, however, and using the Platt

Amendment, the US made Cuba a de facto colony (a point developed in

greater detail below). We also took over other Spanish possessions,

including Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines (after extended, bloody

fighting against Filipino independence forces).

The War of 1898 heightened US interest in the circum-Caribbean and in a canal linking the Caribbean and the Pacific. The battleship Oregon, steamed from the Pacific Ocean around South America, arriving at Cuba after the war had already ended. No medals, no parades. Navy supporters did not like the idea of ships arriving too late to fight.

The creation of the new nation of Panama (encouraged and supported by the US) and the construction of the Panama Canal [1904-14, see map] gives the US another strategic property to defend. The 1903 treaty between the two nations greatly favored the US, at the expense of Panama's sovereignty and economic interests.

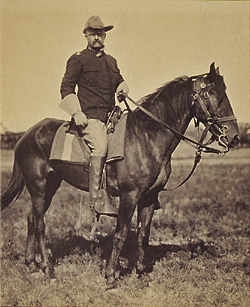

The architect of Panama's independence, US President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919, shown in the photo at right taken in 1898, just after the war in Cuba had ended) also reinterpreted the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 from a statement of non-intervention to an excuse for US interventionism. In 1917, we purchase the Virgin Islands from Denmark to gain bases on this strategic approach to the Panama Canal through the Caribbean Sea. Massive US investments throughout Latin America give US corporations and therefore the US government strong interests to protect. As the cartoon at the right shows, Roosevelt advised America to "speak softly but carry a big stick."

- =========== Along with intervening to create the nation of Panama, the US exhibited other highhanded tactics in Cuba. Thanks to the Platt Amendment to the Cuban Constitution, that nation becomes a virtual US colony just after gaining its independence from Spain. We could manipulate Cuban politics, take over its economy, and repeatedly land troops there--all "constitutional," thanks to this imposed arrangement. Orville Hitchcock Platt, long-time conservative Republican senator from Connecticut (1879-1905), introduced the

amendment that bears his name. Earlier statements on behalf of Cuban independence and autonomy vanished from political memory.

The Platt Amendment, passed by the the U.S. 56th Congress, 1901, signed by both nations May 22, 1903.

That in fulfillment of the declaration contained in the joint resolution approved April twentieth, eighteen hundred and ninety-eight, entitled 'For the recognition of the independence of the people of Cuba, demanding that the Government of Spain relinquish its authority and government in the island of Cuba, and to withdraw its land and naval reserve forces from Cuba and Cuban waters, and directing the President of the United States to use the land and naval forces of the United States to carry these resolutions into effect,' the President is hereby authorized to 'leave the government and control of the island of Cuba to its people' so soon as a government shall have been established in said island under a constitution which, either as a part thereof or in an ordinance appended thereto, shall define the future relations of the United States with Cuba, substantially as follows:

- That the government of Cuba shall never enter into any treaty or other compact with any foreign power or powers which will impair or tend to impair the independence of Cuba, or in any manner authorize or permit any foreign power or powers to obtain by colonization or, for military or naval purposes or otherwise, lodgment in or control over any portion of said island.

- That said government shall not assume or contract any public debt, to pay the interest upon which, and to make reasonable sinking fund provision for the ultimate discharge of which, the ordinary revenues of the island, after defraying the current expenses of government shall be inadequate.

- That the government of Cuba consents that the United States may exercise the right to intervene for the preservation of Cuban independence, the maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property, and individual liberty, and for discharging the obligations with respect to Cuba imposed by the Treaty of Paris on the United States, now to be assumed and undertaken by the government of Cuba.

- That all Acts of the United States in Cuba during its military occupancy thereof are ratified and validated, and all lawful rights acquired thereunder shall be maintained and protected.

- That the government of Cuba will execute and as far as necessary extend, the plans already devised or other plans to be mutually agreed upon, for the sanitation of the cities of the island, to the end that a recurrence of epidemic and infectious diseases may be prevented, thereby assuring protection to the people and commerce of Cuba, as well as to the commerce of the southern ports of the United States and of the people residing therein.

- That the Isle of Pines shall be omitted from the proposed constitutional boundaries of Cuba, the title thereto being left to future adjustment by treaty.

- That to enable the United States to maintain the independence of Cuba, and to protect the people thereof, as well as for its own defence, the government of Cuba will sell or lease to the United States land necessary for coaling or naval stations at certain specified points, to be agreed upon with the President of the United States.

- That by way of further assurance the government of Cuba will embody the foregoing provisions in a permanent treaty with the United States.

- =========== Indeed, Latin American leaders fought long and hard against European and US claims that they had a right to intervene in and invade other nations. Carlos Calvo (1822-1906), a jurist and diplomat from Argentina, pushed unsuccessfully for acceptance of a non-intervention doctrine. Writing in 1896, he asserted that "aside from political motives these interventions have nearly always had as apparent pretexts, injuries to private interests, claims and demands for pecuniary indemnities in behalf of subjects. . . . According to strict international law, the recovery of debts and the pursuit of private claims does not justify de plano the armed intervention of government, and , since European states invariably follow this rule in their reciprocal relations, there is no reason why they should not also impose it upon themselves in their relations with the nations of the new world. . . . The rule that in more than one has it has been attempted to impose on American states is that foreigners merit more regard and privileges more marked and extended than those accorded even to the nationals of the country where they reside. This principle is intrinsically contrary to the law of equality of nations." In 1902, Argentina's minister to Washington, Luis M. Drago (1859-1921), asserted that debt collection did not give a nation the right to intervene: "there can be no territorial expansion in America on the part of Europe, nor any oppression of the peoples of this continent, because an unfortunate financial situation may compel some one of them to the fulfillment of its promises. In a word, the principle which she would like to see recognized is: that the public debt can not occasion armed intervention nor even the actual occupation of the territory of American nations by a European power."

- =========== Writing in 1926, Peruvian intellectual and politician Victor Haya de la Torre (1895-1979) offered a leftist interpretation of hemispheric relations. He also organized APRA (Popular Revolutionary American Alliance), a populist political party to fight the problems he diagnosed.

The history of the political and economic relations between Latin America and the United States, especially the experience of the Mexican Revolution, lead to the following conclusions:

- The governing classes of the Latin American countries--landowners, middle class or merchants--are allies of North American Imperialism.

- These classes have the political power in our countries, in exchange for a policy of concessions, of loans, of great operations which they--the capitalists, landowners or merchants and politicians of the Latin American dominant classes---share with Imperialism.

- As a result of this alliance the natural resources which form the riches of our countries are mortgaged or sold, and the working and agricultural classes are subjected to the most brutal servitude. Again, this alliance produces political events which result in the loss of national sovereignty: Panama, Nicaragua, Cuba, Santo Domingo [Dominican Republic], are really protectorates of the United States.

You'll find more writing by de la Torre on the Primary Sources Page.

- ===========

Faced with such criticism from many in Latin America, in 1928, Charles Evans Hughes (1862-1948), at the behest of the Republican Hoover administration, presented the US rationale for its interventions. Hughes has served as secretary of state under Harding and in 1930 became a very conservative voice as chief justice of the Supreme Court.

What are we to do when government breaks down and American citizens are in danger of their lives? Are we to stand by and see them killed because a government, in circumstances which it cannot control and for which it may not be responsible, can no longer afford reasonable protection? I am not speaking of sporadic acts of violence, or of the rising of mobs, or of those distressing incidents which may occur in any country, however well administered. I am speaking of the occasion where government itself is unable to function for a time. . . . Now it is a principle of international law that in such a case a government is fully justified in taking action--I would call it interposition of a temporary character--for the purpose of protecting the lives and property of its nationals. . . . Of course, the United States cannot forego the right to protect its citizens. No country should forego its right to protect its citizens.

- =========== Faced with such forceful, rising anti-imperialist sentiment, and slammed by the Great Depression of 1929, Hoover began moving the US away from interventionism. His successor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945), went even further with his "Good Neighbor Policy." The US finally and officially dropped its imperious insistence on its right of interventions. At the Seventh International Conference of American States, held in Montevideo, Uruguay, in December 1933, the US signed an agreement supporting nonintervention, albeit with reservations.

Article 4: States are juridically equal, enjoy the same rights, and have equal capacity in their exercise. The rights of each one do not depend upon the power which it possesses to assure its exercise, but upon the simple fact of its existence as a person under international law.

Article 8: No state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.

Article 9: The jurisdiction of states within the limits of national territory applies to all the inhabitants. Nationals and foreigners are under the same protection of the law and the national authorities, and the foreigners do not claim rights over or more extensive than those of the nations.

Article 11: The contracting states definitely establish as the rule of the conduct the precise obligation not to recognize territorial acquisitions or special advantages which have been obtained by force whether this consists in the employment of arms, threatening diplomatic representations, or in any other effective coercive measure. The territory of a state is inviolable and may not be the object of military occupation nor of any other measures of force imposed by another state directly or indirectly or for any motive whatever even temporarily.

Reservations made at signature by the United States of America:

The United States Government in all its international associations and relationships and conduct will follow scrupulously the doctrines and policies which it has pursued since March 4 which are embodied in . . . the law of nations as generally recognized and accepted.

- ============

The Roosevelt administration also abrogated (cancelled) the Platt Amendment on May 29, 1934, thus abandoning its "legal" right of intervention in Cuba. After a lull in military interventions under Roosevelt and Truman, however, the Republican Eisenhower administration would renew intervention with a vengeance during the 1950s. Thus both foreign and domestic affairs for the Latin American nations become more difficult. Internal politics became much more complex as the new political contenders discussed above exerted influence and pursued their often conflicting interests. Not surprisingly, the political systems of many nations cracked under the strain. We'll find military dictatorships, revolutions, and other extreme forms on political organization on the rise in the twentieth century. All of this political conflict proved challenging for the United States, which more than anytime wanted stability and a good, profitable investment climate in its neighbors to the south.

A Nationalist Backlash: Anti-Interventionism in Latin America

- =========== In Mexico, the great destruction and divisions of the Mexican Revolution generated tremendous nationalism, a violent reaction to the long dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz (1830-1915, shown in the portrait at the right). Many revolutionaries fought to end what they viewed as foreign domination of their economy, especially by the US. Pancho Villa [pictured at left] provided the most graphic and violent anti-American actions. In the spring of 1916 Villa's troops shot and killed 17 US miners. Later Villa and perhaps 500 troops invaded Columbus, New Mexico, and shot and killed another 17 US citizens. Nationalism would spur many later outbreaks of anti-Americanism as well. Mexico's new revolutionary constitution written in 1917 would reflect the nation's strong economic nationalism by declaring all subsoil resources to be inalienable (they could not be sold to foreigners). President Lazaro Cardenas would act on this nationalism by nationalizing foreign oil company holdings in 1938.

- Diaz had gained hero status among liberals by fighting against occupying French forces in the 1860s. As a reward, he won election as president in 1880. Following four years of constitutional rule, he developed a personal dictatorship and controlled the nation from 1884 until his ouster in 1911. The Diaz regime illustrates as clearly as any government the failures of 19th-century elite-based policies. Operating under the influence is his Positivist advisors, the "cientificos," Diaz purposely created a Mexico of mostly have-nots, the majority Indian peasants, presided over by a tiny elite of "haves." Historian Peter Bakewell (A History of Latin America, 1997, pp. 421-22) explains the pernicious impact of this racist philosophy in combination with social Darwinism.

The moneyed were happy to assume that a process of natural selection had lifted them to their superior position in society. They found it equally comforting to think of the poor as naturally being so as a result of innate incapacities. And yet more convenient was the notion that governments would be going against principles of Nature if they tried to raise the poor and servile from their inferior state. . . . Positivism and Darwinism thus instructed the wealthy and the aspirants to wealth in Latin America that possession of riches was part of the natural order of things, an outcome of their inherent superiority, and that conscious attempts to improve the conditions of the poor were doomed to failure because they contradicted natural laws.

The violent Mexican Revolution and many others to follow would of course demonstrate the complete bankruptcy of this fallacious doctrine.

-

The dictator and his advisors believed that they should invite foreign capital, expertise, technology, and immigrants to Mexico to help uplift the country. Their racist point of view considered white foreigners superior to the mixed-blood (mestizo) and indigenous Mexicans. They hoped to improve the nation with foreign genetic and monetary infusions. Thus foreigners received great subsidies and opportunities not open to Mexicans. Foreign corporations, many based in the neighboring US, dominated mining, oil, railroads, plantation agriculture, and other key economic areas. "Poor Mexico, so far from God, so near the United States" went the popular lament. The dictator and his advisors believed that they should invite foreign capital, expertise, technology, and immigrants to Mexico to help uplift the country. Their racist point of view considered white foreigners superior to the mixed-blood (mestizo) and indigenous Mexicans. They hoped to improve the nation with foreign genetic and monetary infusions. Thus foreigners received great subsidies and opportunities not open to Mexicans. Foreign corporations, many based in the neighboring US, dominated mining, oil, railroads, plantation agriculture, and other key economic areas. "Poor Mexico, so far from God, so near the United States" went the popular lament.

- =========== After the massive fighting ended, the decade of the 1920s became one of reconstructing the nation. Artists, philosophers, writers, composers all lauded "lo Mexicano"--things Mexican -- in an attempt to draw people together and to heal the wounds of the preceding bloody decade. Murals and music proclaimed the pride Mexicans took in leaving their neofeudal past behind and marching forward together in the twentieth century. Minister of Public Education (1920-24) Jose Vasconcelos wrote optimistically of the "Cosmic Race" of Mexicans who could look to a brighter future thanks to the Revolution.

- =========== Similar cultural nationalism arose in other countries as writers, politicians, and philosophers celebrated their own heritage and roots, now increasingly viewed as superior to not inferior to things European.

Cuba's independence hero, Jose Marti (1853-95), writing the year before his death, sharply criticism the US, which he held as inferior to Latin America. "It is surely appropriate, and even urgent, to put before our America the entire American truth, about the Saxon as well as the Latin, so that too much faith in foreign virtue will not weaken us in our formative years with an unmotivated and baneful distrust of what is ours. From the standpoints of justice and a legitimate social science, it should be recognized that, in relation to the ready compliance of the one and the obstacles of the other, the North American character has gone downhill since the winning of independence, and is today less human and virile; whereas the Spanish American character today is in all ways superior, in spite of its confusion and fatigue. . . . [We must] demonstrate two useful truths to our America: the crude, uneven, and decadent character of the United States, and the continuous existence there of all the violence, discord, immorality, and disorder blamed upon the peoples of Spanish America." On May 18, 1895, the day before his death, Marti (now fighting against the Spaniards) wrote to a friend that he worked to keep "those Imperialists up there [in the US] and the Spaniards from annexing the peoples of our America to the savage and brutal North, which holds them in contempt; with our own blood we are blocking their path. I have lived in the monster [the US] and know its entrails--and my sling is that of David." [Ironically and showing a profound ignorance of Marti's anti-American views, the Reagan administration would later name their propaganda radio beamed at Castro's Cuba "Radio Marti."] Cuba's independence hero, Jose Marti (1853-95), writing the year before his death, sharply criticism the US, which he held as inferior to Latin America. "It is surely appropriate, and even urgent, to put before our America the entire American truth, about the Saxon as well as the Latin, so that too much faith in foreign virtue will not weaken us in our formative years with an unmotivated and baneful distrust of what is ours. From the standpoints of justice and a legitimate social science, it should be recognized that, in relation to the ready compliance of the one and the obstacles of the other, the North American character has gone downhill since the winning of independence, and is today less human and virile; whereas the Spanish American character today is in all ways superior, in spite of its confusion and fatigue. . . . [We must] demonstrate two useful truths to our America: the crude, uneven, and decadent character of the United States, and the continuous existence there of all the violence, discord, immorality, and disorder blamed upon the peoples of Spanish America." On May 18, 1895, the day before his death, Marti (now fighting against the Spaniards) wrote to a friend that he worked to keep "those Imperialists up there [in the US] and the Spaniards from annexing the peoples of our America to the savage and brutal North, which holds them in contempt; with our own blood we are blocking their path. I have lived in the monster [the US] and know its entrails--and my sling is that of David." [Ironically and showing a profound ignorance of Marti's anti-American views, the Reagan administration would later name their propaganda radio beamed at Castro's Cuba "Radio Marti."]

- =========== Perhaps no one voiced rising cultural nationalism better than Uruguayan writer Jose Enrique Rodo ((1872-1917,shown at right in the year of his death) in his book titled Ariel (1900). While acknowledging the considerable economic and technological achievements of the United States, Rodo sternly warned Latin Americans against mindless imitation of "Caliban." He blasted US materialism and cultural shallowness.

<"North American life, in fact, perfectly describes the vicious circle identified by Pascal: the fervent pursuit of well-being that - no object beyond itself. North American prosperity is as great as its inability to satisfy even an average concept of human destiny. In spite of its titanic accomplishments and the great force of will that those accomplishments represent, and in spite of its incomparable triumphs in all spheres of material success, it is nevertheless true that as an entity this civilization creates a singular impression of insufficiency and emptiness. . . They live for the immediate reality, for the present, and thereby subordinate all their activity to the egoism of personal and collective well being. . . . Sensibility, intelligence, customs--everything in that enormous land is characterized by a radical ineptitude for selectivity which, along with the mechanistic nature of its materialism and its politics, nurtures a profound disorder in anything having to do with idealism.. . . The idealism of beauty does not fire the soul of a descendant of austere Puritans. Nor does the idealism of truth. He scorns as vain and unproductive any exercise of thought that does not yield an immediate result.

- In societies, as in literature or in art, blind imitation produces an inferior copy of the original. Respect for one's own independence, judgment, and personality is a matter of pride. . . . We Latin Americans have our own inheritance, a great ethnic tradition to maintain, a sacred bond uniting us to the past, linking us to our history. Our honor bounds us to preserve this tradition for the future. Any external influence which we accept must not preclude our own fidelity to the past. We must apply our own genius to the process of fusing and molding the future. . . .

- [Rodo exhorted Latin Americans to be guided by their spirituality; not by the materialism rampant in North America.]

Picture the Americas of the future. It will be hospitable to the intellect; it will give flight to the spirit; it will cradle the soul. It will be thoughtful, without sacrificing action; it will be serene and strong without abjuring enthusiasm; it will radiate charm while engendering thought. . . . I ask you to give of your spirit and soul for this labor for the future. For that reason I seek inspiration in the gentle and lovely image of Ariel here by my side. This bountiful Spirit selected by the genius of Shakespeare serves as our symbol. The sculptor rendered the statue appropriately spiritual. Ariel is the beacon and the higher truth. Ariel is that sublime sentiment of the perfectibility of the human being. Ariel, the spirit, is the crowning glory of evolution.

- =========== Economic nationalism is the belief that the people of a nation, not foreigners and foreign corporations, should own and control their own economy and resources. In 1939, for example, President Lazaro Cardenas nationalized the foreign oil holdings of Mexico. An early proponent of economic nationalism, the Brazilian intellectual Alberto Torres (1865-1917) wrote influentially between 1909 and 1915. His argument equating economic development and nationalism would strongly influence many officers of the Brazilian military. To exercise "real sovereignty" and express "true nationalism," he said, a nation must control its own industry and trade. This summary of his ideas comes from his 1914 book O Problema Nacional Brasileiro (The National Brazilian Problem).

- OUR NATION has renounced its own heritage. Foreigners seize it. Foreign companies, recently arrived foreign immigrants, foreign businessmen without any headquarters in our country, foreigners in transit or with a residence just long enough for them to enrich themselves take advantage of our vast regions, our soil, our railroads, and our natural sources of wealth. They purchase our property; they take advantage of the credit extended by our banks. They seem to have future projects that would divide our country into spheres of influence. It is impossible to disguise the fear provoked by the contrast between these undeniable facts and the benign, even permissive attitude of our governments toward the growing reality of foreign domination.

The Brazilian people have no idea of the national danger that suddenly confronts them, even threatens them. Foreigners control the national patrimony as well as the exports. Our territorial integrity, our independence, and our sovereignty exist at the mercy of the great economic and military powers. ...

There can be no doubt about the present alarming economic situation of our country with its disequilibrium between production and consumption and the commercial and industrial inflation. Powerful foreign businesses, whose activities conflict with the best interests of our nation, exploit us mercilessly. The economic ideas that come to us from abroad are adverse and always alien to our best interests. Indifferent to our priorities and needs, foreigners view Brazil exclusively as a source of profits.

Their interests do not complement ours. They persuade some Brazilians with their logic to the extent that they have come to favor foreign exploitation to the detriment of their own Brazil.

- Our financial crises further expose us to foreign domination. Absorbed in matters of foreign credit and crushed by the pressure of debts, the governments descend to the lowly status of subordinates, showing real fear of foreign creditors and capitalist pressures. They are unable to give the nation the direction needed to serve its own best interests. They are slaves to foreign interests. They compromise the nation. Above all else, the independence of a people is founded on their economy and their finances....

In order for a nation to remain independent, it is imperative to preserve the vital organs of nationality: the principal sources of wealth, the industries of primary products, the instrumentalities and agents of economic vitality and circulation, transportation and internal commerce. There must be neither monopolies nor privileges, but there must exist ample guarantees and protection for free labor, individual initiative, small-scale production, and the distribution of wealth.

A people cannot be free if they do not control their own sources of wealth, produce their own food, and direct their own industry and commerce.

- =========== Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904-73) voiced poetic opposition to the growing US presence. In his poem "The United Fruit Co.," he criticized US economic domination of Latin America and US support for dictators in the region. Born Neftali Ricardo Reyes Basoalto, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971. A Marxist, he served as Salvador Allende's ambassador to France from 1970 until his death from cancer three years later. A US-backed military coup overthrew and killed Allende (September 11) less than two weeks before Neruda's own death on September 23, 1973.

- The United Fruit Co.

When the trumpets had sounded and all

was in readiness on the face of the earth,

Jehovah divided his universe:

Anaconda, Ford Motors,

Coca-Cola Inc., and similar entities:

the most succulent item of all,

The United Fruit Company Incorporated [note: United Fruit lobbying prompted the CIA to overthrow the government of Guatemala in 1954]

reserved for itself: the heartland reserved for itself: the heartland

and coasts of my country,

the delectable waist of America.

They rechristened their properties:

the "Banana Republics"--

and over the languishing dead,

the uneasy repose of the heroes

who harried that greatness,