Pre-History and Colonial Problems

Human habitation in Latin America probably goes back at least 12,000 to 15,000

years. Over the millenia creative, adaptive humans found ways to live

and even prosper under a wide range of natural conditions. Tainos (Arawaks)

learned to harvest the natural riches of the Caribbean islands. Caribs

and others  inhabited the the Amazonian rainforests and later, using long canoes,

migrated to many Caribbean Islands--often displacing Tainos. With its

varied climates and soils, Latin America produced an abundance of food.

Squash was probably the first food crop domesticated by Pre-Columbian

Indians. Precursors of the Inca domesticated highly specialized food

crops, including the all-important potato, to grow high in the Andes

Mountains. Researchers have found precursors to maize (corn) along the

Gulf of Mexico in what is now the Mexican state of Tabasco that dates

back 6,000 years (5100 BCE). Later varieties of corn would become the

staff of live for the Maya and other Mesoamericans. Pre-Columbian Mexicans

apparently also cultivated sunflower seeds 4000 years ago and cotton

(about 2500 BCE). Indians also domesticated a variety of beans, cacao

(for chocolate!), peanuts, tobacco, tomatoes, and many other foods indigenous

to the Americas.

The large number of impressive pre-Columbian archaeologial sites attests to the imagination, organization, and energy of these first inhabitants

of the Americas. The central Mexican site of Tenochtitlan, built by the warlike Aztecs, flourished from its founding about 1325 until its conquest and destruction by Henan Cortez and his Spanish soldiers in 1521. Click here to view a map of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in Central Mexico.

Tikal (pictured at the left), reined for centuries as among the most impressive, properous Mayan cities. Located in northeastern Guatemala, the city's inhabitants established extensive trade networks and sophisticated agricultural production. The city's quick, mysterious decline and abandonment about 850 CE continues to confound scholars. Did intercity wars ravage the ares? Did they abuse the environment and thus kill off food production? Did a natural disaster strike? Scholars continue to search for an explanation.

inhabited the the Amazonian rainforests and later, using long canoes,

migrated to many Caribbean Islands--often displacing Tainos. With its

varied climates and soils, Latin America produced an abundance of food.

Squash was probably the first food crop domesticated by Pre-Columbian

Indians. Precursors of the Inca domesticated highly specialized food

crops, including the all-important potato, to grow high in the Andes

Mountains. Researchers have found precursors to maize (corn) along the

Gulf of Mexico in what is now the Mexican state of Tabasco that dates

back 6,000 years (5100 BCE). Later varieties of corn would become the

staff of live for the Maya and other Mesoamericans. Pre-Columbian Mexicans

apparently also cultivated sunflower seeds 4000 years ago and cotton

(about 2500 BCE). Indians also domesticated a variety of beans, cacao

(for chocolate!), peanuts, tobacco, tomatoes, and many other foods indigenous

to the Americas.

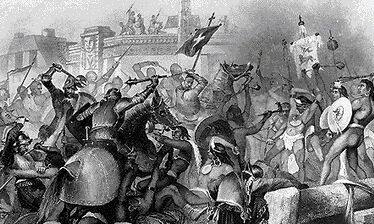

The large number of impressive pre-Columbian archaeologial sites attests to the imagination, organization, and energy of these first inhabitants

of the Americas. The central Mexican site of Tenochtitlan, built by the warlike Aztecs, flourished from its founding about 1325 until its conquest and destruction by Henan Cortez and his Spanish soldiers in 1521. Click here to view a map of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in Central Mexico.

Tikal (pictured at the left), reined for centuries as among the most impressive, properous Mayan cities. Located in northeastern Guatemala, the city's inhabitants established extensive trade networks and sophisticated agricultural production. The city's quick, mysterious decline and abandonment about 850 CE continues to confound scholars. Did intercity wars ravage the ares? Did they abuse the environment and thus kill off food production? Did a natural disaster strike? Scholars continue to search for an explanation.

Pre-Columbian

inhabitants lacked large, sturdy beasts of burden, like oxen or horses.

For that reason, they had not bothered with the wheel, present only

on a child's toy. Andean Indians had domesticated a number of animals,

including the llama. Capable of carrying moderate loads, the llama remains

a useful work animal on the rugged trails of Andean South America. Spanish

introduction of horses, cattle, sheep, and many other plants and animals

would produce tremendous social and economic changes in Latin America.

The epic voyages Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and the subsequent conquest

of this New World by the Spanish and Portuguese and other colonial powers

wrought tremendous change. Columbus recorded in his

diary and in subsequent letters his impressions of that fateful

day-- October 12, 1492-- and after-- the first meeting between Europeans

and those he called "Indians" (thinking that he had reached the East

Indies, the spice islands). Read Columbus's observations, using the

link above, and note his ethnocentric observations about the Caribbean

islands and their people. Pre-Columbian

inhabitants lacked large, sturdy beasts of burden, like oxen or horses.

For that reason, they had not bothered with the wheel, present only

on a child's toy. Andean Indians had domesticated a number of animals,

including the llama. Capable of carrying moderate loads, the llama remains

a useful work animal on the rugged trails of Andean South America. Spanish

introduction of horses, cattle, sheep, and many other plants and animals

would produce tremendous social and economic changes in Latin America.

The epic voyages Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and the subsequent conquest

of this New World by the Spanish and Portuguese and other colonial powers

wrought tremendous change. Columbus recorded in his

diary and in subsequent letters his impressions of that fateful

day-- October 12, 1492-- and after-- the first meeting between Europeans

and those he called "Indians" (thinking that he had reached the East

Indies, the spice islands). Read Columbus's observations, using the

link above, and note his ethnocentric observations about the Caribbean

islands and their people.

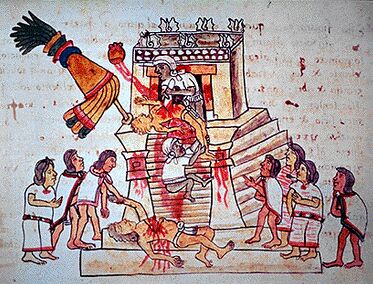

As evidenced in the writings of Columbus and others, Spaniards arrived

in the New World laden with the ethnocentrism and sense of superiority

typical of conquistadors and colonizers. Some native practices, however,

gave the Spaniards ample reason to feel justified in their conquest

of these strange, new lands. Natives in the Caribbean dressed immodestly.

To the Spaniards, their nudity gave proof of depravity. The Aztecs practiced

ritual human sacrifice. Wielding sharp, black obsidian knives, Aztec

priests, atop grand pyramids, cut out the hearts of victims to appease

their gods. The illustration at the right comes from an Aztec codex,

a sacred book kept in the temple. Scribes painted the ritual calendar,

divination, ceremonies, and speculations on the gods and the universe

on these codices. They used a combination of pictography, ideograms,

and phonetic symbols to record their culture on deerskin or agave-fibre

paper. Only a small fraction of these escaped destruction by the zealous

Spaniards. Surviving speciments are given names, such as the Codex Borbonicus,

Codex Borgia, Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, and Codex Cospi.

As evidenced in the writings of Columbus and others, Spaniards arrived

in the New World laden with the ethnocentrism and sense of superiority

typical of conquistadors and colonizers. Some native practices, however,

gave the Spaniards ample reason to feel justified in their conquest

of these strange, new lands. Natives in the Caribbean dressed immodestly.

To the Spaniards, their nudity gave proof of depravity. The Aztecs practiced

ritual human sacrifice. Wielding sharp, black obsidian knives, Aztec

priests, atop grand pyramids, cut out the hearts of victims to appease

their gods. The illustration at the right comes from an Aztec codex,

a sacred book kept in the temple. Scribes painted the ritual calendar,

divination, ceremonies, and speculations on the gods and the universe

on these codices. They used a combination of pictography, ideograms,

and phonetic symbols to record their culture on deerskin or agave-fibre

paper. Only a small fraction of these escaped destruction by the zealous

Spaniards. Surviving speciments are given names, such as the Codex Borbonicus,

Codex Borgia, Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, and Codex Cospi.

More

deadly than sword cuts, epidemic diseases to which American Indians

had no immunities, decimated the population of first the Caribbean and

later continental Latin America. Millions of Indians died of mass epidemics

of smallpox, measles, typhus, influenza, yellow fever, dysentary, malaria,

and other diseases. Promiscuous sailors also touched off a worldwide

epidemic of venereal disease. Spaniards and Portuguese imposed new institutions

to control and extract wealth from their newly established colonies.

Gradually, a distinct Spanish cultural stamp appeared throughout Spanish

America: language, religion, urban geography, political and economic

organization all took on a Spanish flavor.

Take a few minutes to read about the legacies of the Mexican and Peruvian Conquests. Explore the PBS site about the Spanish Conquistadors Specifically, read the twin essays on the following pages about the

Legacy of the Mexican Conquest by Hernan Cortes and the Legacy of the Conquest of Peru by Francisco Pizarro. Consider the terribles costs to native peoples of the Spanish conquest. Can you see any benefits (positives) to Spain's establishing rule over the Aztecs and Incas?

The conquistadors quickly subjugated the indigenous population and forced them into slavery or other forms of forced labor. Spaniards justified Indian slavery using an ingenius legal sophistry called the Requerimiento. Authored in 1514 under the authority of King Charles I of Spain, conquistadors read this document to Indians of the new world. It briefly explains Spain's assertion of its legal and moral right to rule over the inhabitants of Latin America. It also provides a rationale for a "just war." Legalistic Spaniards devised this doctrine so that you could declare a "just war" and thus "legally" enslave Indians who refused to agree with all the statements of the requerimiento [abridged portion below]. Notice the dire warning in the last paragraph to those who do not submit. Of course, not knowing Spanish, most Indians had no idea what the reading meant but found themselves enslaved nonetheless.

On behalf of the king and the queen, subjugators of barbarous peoples, we, their servants, notify and make known to you as best we are able, that God, Our Lord, living and eternal, created the heavens and the earth, and a man and a woman, of whom you and we and all other people of the world were, and are, the descendants. Because of the great numbers of people who have come from the union of these two in the five thousand year, which have run their course since the world was created, it became necessary that some should go in one direction and that others should go in another. Thus they became divided into many kingdoms and many provinces, since they could not all remain or sustain themselves in one place.

Of all these people God, Our Lord, chose one, who was called Saint Peter, to be the lord and the one who was to be superior to all the other people of the world, whom all should obey. He was to be the head of the entire human race, wherever men might exist. God gave him the world for his kingdom and jurisdiction. God also permitted him to be and establish himself in any other part of the world to judge and govern all peoples, whether Christian, Moors, Jew, Gentiles, or those of any other sects and beliefs that there might be. He was called the Pope.

One of the past Popes who succeeded Saint Peter, as Lord of the Earth gave these islands and mainlands of the Ocean Sea [the Atlantic Ocean] to the said King and Queen and to their successors, with everything that there is in them, as is set forth in certain documents which were drawn up regarding this donation in the manner described, which you may see if you so desire.

In consequence, Their Highnesses are Kings and Lords of these islands and mainland by virtue of said donation. Certain other isles and almost all [the native peoples] to whom this summons has been read have accepted Their Highnesses as such Kings and Lords, and have served, and serve, them as their subjects as they should, and must, do, with good will and without offering any resistance. You are constrained and obliged to do the same as they.

Consequently, as we best may, we beseech and demand that you understand fully this that we have said to you and ponder it, so that you may understand and deliberate upon I for a just and fair period and that you accept the Church and Superior Organization of the whole world and recognize the Supreme Pontiff, called the Pope, and that in his name, you acknowledged the King and Queen, as the lords and superior authorities of these islands and mainlands by virtue of the said donation.

If you do not do this, however, or resort maliciously to delay, we warn you that, with the aid of God, we will enter your land against you with force and will make war in every place and by every means we can and are able, and we will then subject you to the yoke and authority of the Church and Their Highnesses. We will take you and your wives and children and make them slaves, and as such we will sell them, and will dispose of you and them as Their Highnesses order. And we will take your property and will do to you all the harm and evil we can, as is done to vassals who will not obey their lord or who do not wish to accept him, or who resist and defy him. We avow that the deaths and harm which you will receive thereby will be your own blame, and not that of Their Highnesses, nor ours, nor of the gentlemen who come with us.

Spanish and Portuguese conquerors quickly enslaved Native Americans but also imported Africans as slaves. Portuguese Pero de Magalahaes, described the goal of Europeans who came to Brazil during the 1500s. He recorded his observations in his "History of the Province of Santa Cruz, which we commonly call Brazil" (1576). His descriptions combine acute social observation and European ethnocentrism, making it difficult to establish what he saw and what he projected and assumed. These excerpts come from an English translation by John B. Stetson, Jr., reprinted in a limited edition of 250 copies by the Cortes Society of New York, 1922. Initially, brazilwood, prized for its briliant red dye, provided a major export from Brazil. Sugar, cotton, and other plantation crops, tended by African slaves, quickly became much more lucrative. And like conquistadors everywhere, the Portuguese expended great energy in search of gold.

The first thing they [Portuguese] try to obtain is slaves to work the farms; and any one who succeeds in obtaining two pairs or a half-dozen of them (although he may not have another earthly possession) has the means to sustain his family in a respectable way; for one [slave] fishes for him, another hunts for him, and the rest cultivate and till his fields, and consequently there is no expense for the maintenance of his slaves or of his household. From this, one may infer how very extensive are the estates of those who own two hundred or three hundred slaves, for there are many colonists who have that number and more (p. 41).

Abuse of Indians by conquistadores and encomenderos prompted some--mainly priests-- to protest their actions. In 1511, Friar Antonio de Montesinos delivered a blistering warning to the encomenderos of Hispañola (now Dominican Republic). Notice his dire warning of damnation in the final paragraph.

In order to make your sins against the Indians known to you I have come up on this pulpit, I who am a voice of Christ crying in the wilderness of this island, and therefore it behooves you to listen, not with careless attention, but with all your heart and senses, so that you may hear it; for this is going to be the strangest voice that ever you heard, the harshest and hardest and most awful and most dangerous that ever you expected to hear.

This voice says that you are in mortal sin, that you live and die in it, for the cruelty and tyranny you use in dealing with these innocent people. Tell me, by what right or justice do you keep this Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged a detestable war against these people, who dwelt quietly and peacefully on their own land?

Why do you keep them so oppressed and weary, not giving them enough to eat nor taking care of them in their illness? For with the excessive work you demand of them they fall ill and die, or rather you kill them with your desire to extract and acquire gold every day. And what care do you take that they should be instructed in religion? Are these not men? Have they not rational souls? Are you not bound to love them as you love yourselves? Be certain that, in such a state as this, you can no more be saved than the Moors or Turks. More

deadly than sword cuts, epidemic diseases to which American Indians

had no immunities, decimated the population of first the Caribbean and

later continental Latin America. Millions of Indians died of mass epidemics

of smallpox, measles, typhus, influenza, yellow fever, dysentary, malaria,

and other diseases. Promiscuous sailors also touched off a worldwide

epidemic of venereal disease. Spaniards and Portuguese imposed new institutions

to control and extract wealth from their newly established colonies.

Gradually, a distinct Spanish cultural stamp appeared throughout Spanish

America: language, religion, urban geography, political and economic

organization all took on a Spanish flavor.

Take a few minutes to read about the legacies of the Mexican and Peruvian Conquests. Explore the PBS site about the Spanish Conquistadors Specifically, read the twin essays on the following pages about the

Legacy of the Mexican Conquest by Hernan Cortes and the Legacy of the Conquest of Peru by Francisco Pizarro. Consider the terribles costs to native peoples of the Spanish conquest. Can you see any benefits (positives) to Spain's establishing rule over the Aztecs and Incas?

The conquistadors quickly subjugated the indigenous population and forced them into slavery or other forms of forced labor. Spaniards justified Indian slavery using an ingenius legal sophistry called the Requerimiento. Authored in 1514 under the authority of King Charles I of Spain, conquistadors read this document to Indians of the new world. It briefly explains Spain's assertion of its legal and moral right to rule over the inhabitants of Latin America. It also provides a rationale for a "just war." Legalistic Spaniards devised this doctrine so that you could declare a "just war" and thus "legally" enslave Indians who refused to agree with all the statements of the requerimiento [abridged portion below]. Notice the dire warning in the last paragraph to those who do not submit. Of course, not knowing Spanish, most Indians had no idea what the reading meant but found themselves enslaved nonetheless.

On behalf of the king and the queen, subjugators of barbarous peoples, we, their servants, notify and make known to you as best we are able, that God, Our Lord, living and eternal, created the heavens and the earth, and a man and a woman, of whom you and we and all other people of the world were, and are, the descendants. Because of the great numbers of people who have come from the union of these two in the five thousand year, which have run their course since the world was created, it became necessary that some should go in one direction and that others should go in another. Thus they became divided into many kingdoms and many provinces, since they could not all remain or sustain themselves in one place.

Of all these people God, Our Lord, chose one, who was called Saint Peter, to be the lord and the one who was to be superior to all the other people of the world, whom all should obey. He was to be the head of the entire human race, wherever men might exist. God gave him the world for his kingdom and jurisdiction. God also permitted him to be and establish himself in any other part of the world to judge and govern all peoples, whether Christian, Moors, Jew, Gentiles, or those of any other sects and beliefs that there might be. He was called the Pope.

One of the past Popes who succeeded Saint Peter, as Lord of the Earth gave these islands and mainlands of the Ocean Sea [the Atlantic Ocean] to the said King and Queen and to their successors, with everything that there is in them, as is set forth in certain documents which were drawn up regarding this donation in the manner described, which you may see if you so desire.

In consequence, Their Highnesses are Kings and Lords of these islands and mainland by virtue of said donation. Certain other isles and almost all [the native peoples] to whom this summons has been read have accepted Their Highnesses as such Kings and Lords, and have served, and serve, them as their subjects as they should, and must, do, with good will and without offering any resistance. You are constrained and obliged to do the same as they.

Consequently, as we best may, we beseech and demand that you understand fully this that we have said to you and ponder it, so that you may understand and deliberate upon I for a just and fair period and that you accept the Church and Superior Organization of the whole world and recognize the Supreme Pontiff, called the Pope, and that in his name, you acknowledged the King and Queen, as the lords and superior authorities of these islands and mainlands by virtue of the said donation.

If you do not do this, however, or resort maliciously to delay, we warn you that, with the aid of God, we will enter your land against you with force and will make war in every place and by every means we can and are able, and we will then subject you to the yoke and authority of the Church and Their Highnesses. We will take you and your wives and children and make them slaves, and as such we will sell them, and will dispose of you and them as Their Highnesses order. And we will take your property and will do to you all the harm and evil we can, as is done to vassals who will not obey their lord or who do not wish to accept him, or who resist and defy him. We avow that the deaths and harm which you will receive thereby will be your own blame, and not that of Their Highnesses, nor ours, nor of the gentlemen who come with us.

Spanish and Portuguese conquerors quickly enslaved Native Americans but also imported Africans as slaves. Portuguese Pero de Magalahaes, described the goal of Europeans who came to Brazil during the 1500s. He recorded his observations in his "History of the Province of Santa Cruz, which we commonly call Brazil" (1576). His descriptions combine acute social observation and European ethnocentrism, making it difficult to establish what he saw and what he projected and assumed. These excerpts come from an English translation by John B. Stetson, Jr., reprinted in a limited edition of 250 copies by the Cortes Society of New York, 1922. Initially, brazilwood, prized for its briliant red dye, provided a major export from Brazil. Sugar, cotton, and other plantation crops, tended by African slaves, quickly became much more lucrative. And like conquistadors everywhere, the Portuguese expended great energy in search of gold.

The first thing they [Portuguese] try to obtain is slaves to work the farms; and any one who succeeds in obtaining two pairs or a half-dozen of them (although he may not have another earthly possession) has the means to sustain his family in a respectable way; for one [slave] fishes for him, another hunts for him, and the rest cultivate and till his fields, and consequently there is no expense for the maintenance of his slaves or of his household. From this, one may infer how very extensive are the estates of those who own two hundred or three hundred slaves, for there are many colonists who have that number and more (p. 41).

Abuse of Indians by conquistadores and encomenderos prompted some--mainly priests-- to protest their actions. In 1511, Friar Antonio de Montesinos delivered a blistering warning to the encomenderos of Hispañola (now Dominican Republic). Notice his dire warning of damnation in the final paragraph.

In order to make your sins against the Indians known to you I have come up on this pulpit, I who am a voice of Christ crying in the wilderness of this island, and therefore it behooves you to listen, not with careless attention, but with all your heart and senses, so that you may hear it; for this is going to be the strangest voice that ever you heard, the harshest and hardest and most awful and most dangerous that ever you expected to hear.

This voice says that you are in mortal sin, that you live and die in it, for the cruelty and tyranny you use in dealing with these innocent people. Tell me, by what right or justice do you keep this Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged a detestable war against these people, who dwelt quietly and peacefully on their own land?

Why do you keep them so oppressed and weary, not giving them enough to eat nor taking care of them in their illness? For with the excessive work you demand of them they fall ill and die, or rather you kill them with your desire to extract and acquire gold every day. And what care do you take that they should be instructed in religion? Are these not men? Have they not rational souls? Are you not bound to love them as you love yourselves? Be certain that, in such a state as this, you can no more be saved than the Moors or Turks.

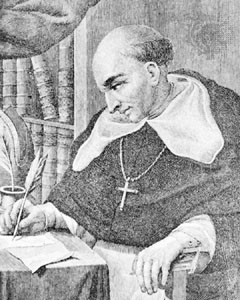

Others, notably Father Bartolomé de las Casas (1474-1566, shown at right) would also defend Indians against Spanish abuses. In one of his many writings, "A Brief Report on the Destruction of

the Indians" (1542) he harshly judged the motives and actions of the Spaniards in the New World. "The reason why the Christians have killed

and destroyed such an infinite number of souls is that they have been

moved by their wish for gold and their desire to enrich themselves in

a very short time." He spent his life working to protect the rights of Indians against abuse, thereby earning his title "Defender of the Indians."

Over time, colonial society became more complex as races mixed and new races

emerged. Spanish and Indian parents yielded the mestizo. Europeans also

mixed with some of the nine million African slaves forcibly brought to Latin America

creating mulattoes. Over time a clear social hierarchy emerged with whites

(peninsular Spaniards and criollos born in the New World) at the top. Mestizos

occupied an inferior position compared with whites and often faced the stigma of illegtimacy. Legally and socially all castas (non-whites) stood at the bottom of the social ladder. Thus racial and social stratification put everyone in his or her assigned place during the colonial era.

Spaniards, acting from ancient Roman practice, quickly established cities throughout Latin America. Lima, Peru became rich and populous owing to its monopoly over trade to the western coast of South America. Much of the wealth passing through Lima originated in the great silver mines of the Andes--the mines that made Potosí, Bolivia, a sixteenth-century boomtown. Historian Lewis Hanke colorfully described social life in Potosí during the mining boom (The Imperial City of Potosí: An Unwritten Chapter in the History of Spanish America, The Hague, Netherlands, 1956).

At one time, in th early part of the seventeenth century, there were some 700 or 800 professional gamblers in the city and 120 prostitutes, among them the redoubtable courtesan Doña Clara, whose wealth and beauty, the chroniclers assure us, were unrivalled. The most extravagant woman in Potosí, she was able to fill her home with the luxuries of Europe and the Orient, for her salon was frequented by the richest miners, who competed enthusiastically for her favors. Vagabonds abounded, and royal officials indignantly reported that there ne'er -do-wells did nothing but dress extravagantly and eat and drink to excess. So high were the stakes that one Juan Fernández dared to start a revoution in 1583, by which he hoped to make himself king of Potosí. He and his brothers planned to seize the city, and "despite the fact that he was a married man, Fernández selected a widow, María Alvarez, to share the throne of his kingdom-to-be." The government learned of this plot and captured Fernández before his revolution could erupt, but this was not the last time that the wealth of Potosí engendered a fever of boundless hope and all-consuming desire among the bold spirits atttracted to that cold and windy city. A thick volume could be compiled on the plots that were hatched. Others, notably Father Bartolomé de las Casas (1474-1566, shown at right) would also defend Indians against Spanish abuses. In one of his many writings, "A Brief Report on the Destruction of

the Indians" (1542) he harshly judged the motives and actions of the Spaniards in the New World. "The reason why the Christians have killed

and destroyed such an infinite number of souls is that they have been

moved by their wish for gold and their desire to enrich themselves in

a very short time." He spent his life working to protect the rights of Indians against abuse, thereby earning his title "Defender of the Indians."

Over time, colonial society became more complex as races mixed and new races

emerged. Spanish and Indian parents yielded the mestizo. Europeans also

mixed with some of the nine million African slaves forcibly brought to Latin America

creating mulattoes. Over time a clear social hierarchy emerged with whites

(peninsular Spaniards and criollos born in the New World) at the top. Mestizos

occupied an inferior position compared with whites and often faced the stigma of illegtimacy. Legally and socially all castas (non-whites) stood at the bottom of the social ladder. Thus racial and social stratification put everyone in his or her assigned place during the colonial era.

Spaniards, acting from ancient Roman practice, quickly established cities throughout Latin America. Lima, Peru became rich and populous owing to its monopoly over trade to the western coast of South America. Much of the wealth passing through Lima originated in the great silver mines of the Andes--the mines that made Potosí, Bolivia, a sixteenth-century boomtown. Historian Lewis Hanke colorfully described social life in Potosí during the mining boom (The Imperial City of Potosí: An Unwritten Chapter in the History of Spanish America, The Hague, Netherlands, 1956).

At one time, in th early part of the seventeenth century, there were some 700 or 800 professional gamblers in the city and 120 prostitutes, among them the redoubtable courtesan Doña Clara, whose wealth and beauty, the chroniclers assure us, were unrivalled. The most extravagant woman in Potosí, she was able to fill her home with the luxuries of Europe and the Orient, for her salon was frequented by the richest miners, who competed enthusiastically for her favors. Vagabonds abounded, and royal officials indignantly reported that there ne'er -do-wells did nothing but dress extravagantly and eat and drink to excess. So high were the stakes that one Juan Fernández dared to start a revoution in 1583, by which he hoped to make himself king of Potosí. He and his brothers planned to seize the city, and "despite the fact that he was a married man, Fernández selected a widow, María Alvarez, to share the throne of his kingdom-to-be." The government learned of this plot and captured Fernández before his revolution could erupt, but this was not the last time that the wealth of Potosí engendered a fever of boundless hope and all-consuming desire among the bold spirits atttracted to that cold and windy city. A thick volume could be compiled on the plots that were hatched.

Ah,

well, urban life has always generated social diversity. Note the varieties

of social class and ethnicity that developed in Lima, Peru, in your online

reading. Finally, other European colonial powers added their cultures,

languages, and bloodlines to the Latin American mix. The French occupied

several Caribbean islands, including the western part of the island of

Hispaniola that would become Haiti after independence. The British likewise

acquired New World real estate, including British Honduras (now Belize),

Jamaica, and some of the Virigin Islands. The Dutch too, whose Caribbean

architecture you see in the photo, occupied three islands off the Venezuelan

coast: Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Even Denmark held some Caribbean colonies

until the United States purchased them in 1917 and made them the US Virgin

Islands. Ah,

well, urban life has always generated social diversity. Note the varieties

of social class and ethnicity that developed in Lima, Peru, in your online

reading. Finally, other European colonial powers added their cultures,

languages, and bloodlines to the Latin American mix. The French occupied

several Caribbean islands, including the western part of the island of

Hispaniola that would become Haiti after independence. The British likewise

acquired New World real estate, including British Honduras (now Belize),

Jamaica, and some of the Virigin Islands. The Dutch too, whose Caribbean

architecture you see in the photo, occupied three islands off the Venezuelan

coast: Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Even Denmark held some Caribbean colonies

until the United States purchased them in 1917 and made them the US Virgin

Islands.

Not everyone gracefully accepted Spanish colonial rule. You will read a protest letter written by

Spanish kings operated under the theory of mercantilism, well explained and criticized by

Adam Smith in "The Wealth of Nations", published in 1776. Smith's forceful call for economic liberalism (free trade, wage labor, private property) would strongly influence independent

Latin American leaders during the nineteenth century.

Some of the best English writers upon commerce set out with observing, that the wealth of a country consists, not in its gold and silver only, but in its

lands, houses, and consumable goods of all different kinds. In the course of their reasoning, however, the lands, houses, and consumable goods seem to

slip out of their memory, and the strain of their argument frequently supposes that all wealth consists in gold and silver, and that to multiply those metals

is the great object of national industry and commerce. The two principles being established, however, that wealth consisted in gold and silver, and that

those metals could be brought into a country which had no mines only by the balance of trade, or by exporting to a greater value than it imported; it

necessarily became the great object of political economy to diminish as much as possible the importation of foreign goods for home consumption, and to

increase as much as possible the exportation of the produce of domestic industry. Its two great engines for enriching the country, therefore, were

restraints upon importation, and encouragements to exportation....

BY restraining, either by high duties, or by absolute prohibitions, the importation of such goods from foreign countries as can be produced at home, the

monopoly of the home market is more or less secured to the domestic industry employed in producing them. Thus the prohibition of importing either live

cattle or salt provisions from foreign countries secures to the grazers of Great Britain the monopoly of the home market for butcher's meat. The high

duties upon the importation of grain, which in times of moderate plenty amount to a prohibition, give a like advantage to the growers of that commodity.

The prohibition of the importation of foreign woollens is equally favorable to the woollen manufacturers. The silk manufacture, though altogether

employed upon foreign materials, has lately obtained the same advantage. The linen manufacture has not yet obtained it, but is making great strides

towards it. Many other sorts of manufacturers have, in the same manner, obtained in Great Britain, either altogether, or very nearly a monopoly against

their countrymen....That this monopoly of the home-market frequently gives great encouragement to that particular species of industry which enjoys it,

and frequently turns towards that employment a greater share of both the labor and stock of the society than would otherwise have gone to it, cannot be

doubted. But whether it tends either to increase the general industry of the society, or to give it the most advantageous direction, is not, perhaps,

altogether so evident....

THOUGH the encouragement of exportation, and the discouragement of importation, are the two great engines by which the mercantile system

proposes to enrich every country, yet with regard to some particular commodities, it seems to follow an opposite plan: to discourage exportation and to

encourage importation. Its ultimate object, however, it pretends, is always the same, to enrich the country by an advantageous balance of trade. It

discourages the exportation of the materials of manufacture, and of the instruments of trade, in order to give our own workmen an advantage, and to

enable them to undersell those of other nations in all foreign markets; and by restraining, in this manner, the exportation of a few commodities, of no

great price, it proposes to occasion a much greater and more valuable exportation of others. It encourages the importation of the materials of

manufacture, in order that our own people may be enabled to work them up more cheaply, and thereby prevent a greater and more valuable

importation of the manufactured commodities....

Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary

for promoting that of the consumer. The maxim is so perfectly self-evident, that it would be absurd to attempt to prove it. But in the mercantile system,

the interest of the consumer is almost constantly sacrificed to that of the producer; and it seems to consider production, and not consumption, as the

ultimate end and object of all industry and commerce. . . .

The importation of gold and silver is not the principal much less

the sole benefit which a nation derives from its foreign trade. Between

whatever places foreign trade is carried on, they all of them derive

two distinct benefits from it. It carries out that surplus part of

the produce of their land and labor for which there is no demand among

them, and brings back in return for it something else for which there

is a demand. It gives a value to their superfluities by exchanging

them for something else, which may satisfy a part of their wants, and

increase their enjoyments. By means of it, the narrowness of the home

market does not hinder the division of labor in any particular branch

of art or manufacture from being carried to the highest perfection.

By opening a more extensive market for whatever part of the produce

of their labor may exceed the home consumption, it encourages them

to improve its productive powers and to augment its annual produce

to the utmost, and thereby to increase the real revenue and wealth

of the society. Clinging to the outmoded practices of mercantilism

contributed to Spain's sharp decline compared with nations such as

Great Britain. Not surprisingly, merchants, planters, and others in

Latin America would also find reason to dislike Spain's mercantilism

and other economic policies. Economic discontent, especially among

creoles, provided one important motive for seeking independence from

Spain.

END Pre-Columbian and Colonial Era

Independence and its Causes

[Flag of Haiti] The latter half of the eighteenth century was an era of revolutions

on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. First the upstart British colonists

of North America broke away from Great Britain. In 1789 the bloody French

Revolution broke out in the name of "liberty, equality, fraternity." Latin

America's first independence movement arose in France's Caribbean colony

of Haiti (Saint Domingue). There slaves, led by Toussaint L'Ouverture,

revolted against their masters on August 22, 1791. After more than a decade

of intense fighting, Haiti declared its independence in 1804.

When revolution broke out in France in 1789, it was almost inevitable that the French overseas colonies would also experience some type of upheaval. In the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), the colony's value to France for its sugar exports further complicated things. In this confused arena François Dominique Toussaint L'Ouverture (1743-1803) took control of the revolution. Born a slave, he was afforded the opportunity by his master to become educated. At first he supported the monarchy, but gradually assumed a more republican stance. Toussaint was unwavering in his pursuit of the abolition of slavery. Here Toussaint warns the Directory (the executive committee which ran the French government) against any attempt to reimpose slavery. Successful in thwarting Paris's desires, he would not be so lucky later. In 1800 Napoleon Bonaparte attempted to reimpose slavery. Toussaint resisted, was captured and brought to France where he died three years later. Napoleon's troops, even though assisted by other European forces, could not subjugate the island. Toussaint's words appear below:

I shall never hesitate between the safety of San Domingo and my personal happiness; but I have nothing to fear. It is to the solicitude of the French Government that I have confided my children.... I would tremble with horror if it was into the hands of the colonists that I had sent them as hostages; but even if it were so, let them know that in punishing them for the fidelity of their father, they would only add one degree more to their barbarism, without any hope of ever making me fail in my duty.... Blind as they are! They cannot see how this odious conduct on their part can become the signal of new disasters and irreparable misfortunes, and that far from making them regain what in their eyes liberty for all has made them lose, they expose themselves to a total ruin and the colony to its inevitable destruction. Do they think that men who have been able to enjoy the blessing of liberty will calmly see it snatched away? They supported their chains only so long as they did not know any condition of life more happy than that of slavery. But to-day when they have left it, if they had a thousand lives they would sacrifice them all rather than be forced into slavery again. But no, the same hand which has broken our chains will not enslave us anew. France will not revoke her principles, she will not withdraw from us the greatest of her benefits. She will protect us against all our enemies; she will not permit her sublime morality to be perverted, those principles which do her most honour to be destroyed, her most beautiful achievement to be degraded. But if, to re-establish slavery in San Domingo, this was done, then I declare to you it would be to attempt the impossible: we have known how to face dangers to obtain our liberty, we shall know how to brave death to maintain it.

I renew the oath that I have made, to cease to live before gratitude dies in my heart, before I cease to be faithful to France and to my duty, before the god of liberty is profaned and sullied by the liberticides, before they can snatch from my hands that sword, those arms, which France confided to me for the defence of its rights and those of humanity, for the triumph of liberty and equality.

The "Declaration Of The Rights Of Man And Citizen" [slightly abridged] authored during the French Revolution well captures some of the essential Enlightenment beliefs that motivated independence leaders in many countries. [Flag of Haiti] The latter half of the eighteenth century was an era of revolutions

on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. First the upstart British colonists

of North America broke away from Great Britain. In 1789 the bloody French

Revolution broke out in the name of "liberty, equality, fraternity." Latin

America's first independence movement arose in France's Caribbean colony

of Haiti (Saint Domingue). There slaves, led by Toussaint L'Ouverture,

revolted against their masters on August 22, 1791. After more than a decade

of intense fighting, Haiti declared its independence in 1804.

When revolution broke out in France in 1789, it was almost inevitable that the French overseas colonies would also experience some type of upheaval. In the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), the colony's value to France for its sugar exports further complicated things. In this confused arena François Dominique Toussaint L'Ouverture (1743-1803) took control of the revolution. Born a slave, he was afforded the opportunity by his master to become educated. At first he supported the monarchy, but gradually assumed a more republican stance. Toussaint was unwavering in his pursuit of the abolition of slavery. Here Toussaint warns the Directory (the executive committee which ran the French government) against any attempt to reimpose slavery. Successful in thwarting Paris's desires, he would not be so lucky later. In 1800 Napoleon Bonaparte attempted to reimpose slavery. Toussaint resisted, was captured and brought to France where he died three years later. Napoleon's troops, even though assisted by other European forces, could not subjugate the island. Toussaint's words appear below:

I shall never hesitate between the safety of San Domingo and my personal happiness; but I have nothing to fear. It is to the solicitude of the French Government that I have confided my children.... I would tremble with horror if it was into the hands of the colonists that I had sent them as hostages; but even if it were so, let them know that in punishing them for the fidelity of their father, they would only add one degree more to their barbarism, without any hope of ever making me fail in my duty.... Blind as they are! They cannot see how this odious conduct on their part can become the signal of new disasters and irreparable misfortunes, and that far from making them regain what in their eyes liberty for all has made them lose, they expose themselves to a total ruin and the colony to its inevitable destruction. Do they think that men who have been able to enjoy the blessing of liberty will calmly see it snatched away? They supported their chains only so long as they did not know any condition of life more happy than that of slavery. But to-day when they have left it, if they had a thousand lives they would sacrifice them all rather than be forced into slavery again. But no, the same hand which has broken our chains will not enslave us anew. France will not revoke her principles, she will not withdraw from us the greatest of her benefits. She will protect us against all our enemies; she will not permit her sublime morality to be perverted, those principles which do her most honour to be destroyed, her most beautiful achievement to be degraded. But if, to re-establish slavery in San Domingo, this was done, then I declare to you it would be to attempt the impossible: we have known how to face dangers to obtain our liberty, we shall know how to brave death to maintain it.

I renew the oath that I have made, to cease to live before gratitude dies in my heart, before I cease to be faithful to France and to my duty, before the god of liberty is profaned and sullied by the liberticides, before they can snatch from my hands that sword, those arms, which France confided to me for the defence of its rights and those of humanity, for the triumph of liberty and equality.

The "Declaration Of The Rights Of Man And Citizen" [slightly abridged] authored during the French Revolution well captures some of the essential Enlightenment beliefs that motivated independence leaders in many countries.

The National Assembly recognizes and declares, in the presence and

under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following rights of man and

citizen.

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions

can be based only upon the common good.

- The aim of every political association is the preservation of the

natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty,

property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- Liberty consists in the power to do anything that does not injure

others; accordingly, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has

no limits except those that assure to the other members of society the

enjoyment of these same rights. These limits can be determined only by

law.

- The law can forbid only such actions as are injurious to society.

Nothing can be forbidden that is not forbidden by the law, and no one

can be constrained to do that which it does not decree.

- Law is the expression of the general will. All citizens have the

right to take part personally, or by their representatives, in its

enactment. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes.

- No man can be accused, arrested, or detained, except in the cases

determined by the law and according to the forms which it has prescribed.

Those who call for, expedite, execute, or cause to be executed arbitrary

orders should be punished; but every citizen summoned or seized by

virtue of the law ought to obey instantly ....

- The law ought to establish only punishments that are strictly and

obviously necessary, and no one should be punished except by virtue of

a law established and promulgated prior to the offence and legally

applied.

- Every man being presumed innocent until he has been declared guilty,

if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, all severity that may not

be necessary to secure his person ought to be severely suppressed by law.

- No one should be disturbed on account of his opinions, even

religious, provided their manifestation does not trouble the public

order as established by law.

- The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most

precious of the rights of man; every citizen can then speak, write, and

print freely, save for the responsibility for the abuse of this liberty

in the cases determined by law.

- The guarantee of the rights of man and citizen necessitates a public

force; this force is then instituted for the advantage of all and not

for the particular use of those to whom it is entrusted.

- For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenses of

administration a general tax is indispensable; it should be equally

apportioned among all the citizens according to their means.

- All citizens have the right to ascertain, by themselves or through

their representatives, the necessary amount of public taxation, to

consent to it freely, to follow the use of it, and to determine the

quota, the assessment, the collection, and the duration of it.

- Any society in which the guarantee of the rights is not assured, or

the separation of powers not determined, has no constitution.

- Property being a sacred and inviolable right, no one can be deprived

of it, unless a legally established public necessity evidently requires

it, under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

The Spanish

colonial system of the Habsburgs had declined sharply and steadily over

the years. In 1700 a new French dynasty, the Bourbons, took over the Spanish

throne and sought to reinvigorate the colonial economy. They faced a formidable

task. Mining revenues had declined as high grade ores disappeared. Smuggling

and piracy cut into royal revenues. Colonial officials often purchased

their offices and worked to recoup their investments as quickly as possible.

Abuses of Indian laborers and of African slaves abounded. Even the native-born

white elite, the criollos or creoles, faced discrimination at the hands

of grasping peninsular Spaniards. What did the empire look like? Here's

a map of the political divisions of

Spanish American empire in 1797. The sentiment for Latin American

independence grew steadily with the abuses of the colonial system. Trying

to centralize colonial governance and increase colonial revenues, the

Bourbons instituted a wide-ranging series of "Reforms." The Bourbon Kings

sent new, powerful officials to Latin America. These intendants tried

to increase tax revenues, enhance military defenses, promote trade, and

bring improved technology to mining and agriculture. Fearing the power

and wealth of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuit religious order), the Bourbons

expelled them from the New World. Note the actual impact of these actions

on Spanish America as you read about them. Despite

the strenuous efforts of the Inquisition, books and ideas of the European

Enlightenment spread to Latin America. You should also examine the important

impact that these new ideas exerted on educated creoles in the New World.

We find ample evidence of discontent among all social classes

during the late eighteenth century. Rural and urban workers faced dismal conditions. The German geographer Alexander von Humboldt left a stark record of conditions in Mexican obrajes or textile factories toward the end of the eighteenth century (Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain, English edition, 1822-23 in 4 volumes).

On visiting these workshops, a traveller is disagreeably struck, not only with the great imperfection of the technical process in the preparation for dyeing, but in the particular manner also with the unhealthiness of the situation, and the bad treatment to which the workmen are explosed. Free men, Indians, and people of colour, are confounded with criminals distributed by justice among the manufactories, in order to be compelled to work. All appear half naked, covered with rags, meagre, and deformed. Every workshop resembles a dark prison. The doors, which are double, remain constantly shut, and the workmen are not permitted to quit the house. Those who are married are only allowed to see their families on Sunday. All are unmercifully flogged, if they commit the smallest trespass on the order established in the manufactory. We have difficulty in conceiving how the proprietors of the obrajes can act in this manner with free man, as well as how the Indian workman can submit to the same treatment with the galley slaves.

In 1781 a multi-class revolt of "Comuneros"

outside Bogotá, Colombia sparked the following demands. Note that the

demands speak to the complaints of many social classes: Indians, mulattoes,

and creoles.

The new tax on tobacco shall be completely abolished.

. . . The total annual tribute of the Indians shall be only four pesos,

and that of mulattoes subject to tribute shall be two pesos. The curates

shall not collect from the Indians any fee for the administration of holy

oils, burials, and weddings, nor shall they complel them to serve as mayordomos

at their saints' festivals. . . . The alcabala [sales tax], henceforth

and forever, shall be two per cent of all fruits, goods, cattle, and articles

of every kind when sold or exchanged. . . . In filling offices of the first,

second, and third classes, natives of America shall be privileged and preferrred

over Europeans, who daily manifest their antipathy toward us. . . . The Spanish

colonial system of the Habsburgs had declined sharply and steadily over

the years. In 1700 a new French dynasty, the Bourbons, took over the Spanish

throne and sought to reinvigorate the colonial economy. They faced a formidable

task. Mining revenues had declined as high grade ores disappeared. Smuggling

and piracy cut into royal revenues. Colonial officials often purchased

their offices and worked to recoup their investments as quickly as possible.

Abuses of Indian laborers and of African slaves abounded. Even the native-born

white elite, the criollos or creoles, faced discrimination at the hands

of grasping peninsular Spaniards. What did the empire look like? Here's

a map of the political divisions of

Spanish American empire in 1797. The sentiment for Latin American

independence grew steadily with the abuses of the colonial system. Trying

to centralize colonial governance and increase colonial revenues, the

Bourbons instituted a wide-ranging series of "Reforms." The Bourbon Kings

sent new, powerful officials to Latin America. These intendants tried

to increase tax revenues, enhance military defenses, promote trade, and

bring improved technology to mining and agriculture. Fearing the power

and wealth of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuit religious order), the Bourbons

expelled them from the New World. Note the actual impact of these actions

on Spanish America as you read about them. Despite

the strenuous efforts of the Inquisition, books and ideas of the European

Enlightenment spread to Latin America. You should also examine the important

impact that these new ideas exerted on educated creoles in the New World.

We find ample evidence of discontent among all social classes

during the late eighteenth century. Rural and urban workers faced dismal conditions. The German geographer Alexander von Humboldt left a stark record of conditions in Mexican obrajes or textile factories toward the end of the eighteenth century (Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain, English edition, 1822-23 in 4 volumes).

On visiting these workshops, a traveller is disagreeably struck, not only with the great imperfection of the technical process in the preparation for dyeing, but in the particular manner also with the unhealthiness of the situation, and the bad treatment to which the workmen are explosed. Free men, Indians, and people of colour, are confounded with criminals distributed by justice among the manufactories, in order to be compelled to work. All appear half naked, covered with rags, meagre, and deformed. Every workshop resembles a dark prison. The doors, which are double, remain constantly shut, and the workmen are not permitted to quit the house. Those who are married are only allowed to see their families on Sunday. All are unmercifully flogged, if they commit the smallest trespass on the order established in the manufactory. We have difficulty in conceiving how the proprietors of the obrajes can act in this manner with free man, as well as how the Indian workman can submit to the same treatment with the galley slaves.

In 1781 a multi-class revolt of "Comuneros"

outside Bogotá, Colombia sparked the following demands. Note that the

demands speak to the complaints of many social classes: Indians, mulattoes,

and creoles.

The new tax on tobacco shall be completely abolished.

. . . The total annual tribute of the Indians shall be only four pesos,

and that of mulattoes subject to tribute shall be two pesos. The curates

shall not collect from the Indians any fee for the administration of holy

oils, burials, and weddings, nor shall they complel them to serve as mayordomos

at their saints' festivals. . . . The alcabala [sales tax], henceforth

and forever, shall be two per cent of all fruits, goods, cattle, and articles

of every kind when sold or exchanged. . . . In filling offices of the first,

second, and third classes, natives of America shall be privileged and preferrred

over Europeans, who daily manifest their antipathy toward us. . . .

[Flag of Venezuela] Creoles took the lead in moving Spanish America toward

independence. From Francisco Miranda and Simón Bolívar in Venzuela to

Father Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morles in Mexico to José de San Martín

in Argentina, able leaders arose to lead the independence forces. In a

famous "Letter from Jamaica," written in 1815, Simón Bolívar (1783-1830)

vehemently expressed the depth of patriot rejection of Spanish dominion.

Spain had reconquered many of the colonies by that year, but Bolívar and

other patriots would fight on to victory.

The hatred that the Peninsula has inspired in us is greater than the ocean between us. It would be easier to have the two continents meet than to reconcile the spirits of the two countries. The habit of obedience, a community of interest, of understanding, of religion; mutual goodwill; a tender regard for the birthplace and good name of our forefathers; in short, all that gave rise to our hopes, came to us from Spain. As a result there was born a principle of affinity that seemed eternal, nothwithstanding the misbehavior of our rulers which weakened that sympathy, or rather, that bond enforced by the domination of their rule. At present the contrarary attitude persists: we are threatend with the fear of death, dishonor, and every harm; there is nothing we have not suffered at the hands of that unnatural step-mother--Spain. The veil has been torn asunder. We have already seen the light, and it is not our desire to be thrust back into darknesss. Then chains have been broken; we have been freed, and now our enemies seek to enslave us anew. For this reason America fights desperately, and seldom has desperation failedl to achieve victory.

[Flag of Venezuela] Creoles took the lead in moving Spanish America toward

independence. From Francisco Miranda and Simón Bolívar in Venzuela to

Father Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morles in Mexico to José de San Martín

in Argentina, able leaders arose to lead the independence forces. In a

famous "Letter from Jamaica," written in 1815, Simón Bolívar (1783-1830)

vehemently expressed the depth of patriot rejection of Spanish dominion.

Spain had reconquered many of the colonies by that year, but Bolívar and

other patriots would fight on to victory.

The hatred that the Peninsula has inspired in us is greater than the ocean between us. It would be easier to have the two continents meet than to reconcile the spirits of the two countries. The habit of obedience, a community of interest, of understanding, of religion; mutual goodwill; a tender regard for the birthplace and good name of our forefathers; in short, all that gave rise to our hopes, came to us from Spain. As a result there was born a principle of affinity that seemed eternal, nothwithstanding the misbehavior of our rulers which weakened that sympathy, or rather, that bond enforced by the domination of their rule. At present the contrarary attitude persists: we are threatend with the fear of death, dishonor, and every harm; there is nothing we have not suffered at the hands of that unnatural step-mother--Spain. The veil has been torn asunder. We have already seen the light, and it is not our desire to be thrust back into darknesss. Then chains have been broken; we have been freed, and now our enemies seek to enslave us anew. For this reason America fights desperately, and seldom has desperation failedl to achieve victory.

The savage fighting raged

on from the initial declarations of independence in 1810 until the final battle of Ayacucho

in 1824. Finally freed of the Spanish yoke, the new creole leaders faced an equally difficult problem--how to govern their newly independent republics.

The savage fighting raged

on from the initial declarations of independence in 1810 until the final battle of Ayacucho

in 1824. Finally freed of the Spanish yoke, the new creole leaders faced an equally difficult problem--how to govern their newly independent republics.

END Independence Era

Political Thought of Simón Bolívar

Fighting against the Spanish for independence had been a long, frustrating,

exhausting, and costly effort. Winning independence was difficult, but

creating a new nation proved equally challenging. The creole elite that

had led the independence movement agreed on only one point. THEY, the "gente

decente," (better people) should rule--not the illiterature, colored masses.

But what form of government should replace the old colonial system? How

should the economy function? These and other thorny questions faced the

creole elites during the difficult decade of the 1820s.

Simón Bolívar (1783-1830, shown at left) labored mightly to resolve the political

dilemmas of Latin America. He called together a Congress in Panama in 1826

to try to get the new republics to cooperate. He failed. Indeed, he would

survive assassination attempts only to be hounded into exile four years

later. He died in Santa Marta, Colombia, too ill to leave the continent

he fought to free. Louis Peru de Lacroix, a French member of Bolivar's staff, described the Liberator in his diary that he kept during their stay at Bucaramanga in 1828, only two years before his death.

The ideas of the Liberator are like his imagination: full of fire, original, and new. They lend considerable sparkle to his conversation, and make it extremely

varied. . . . He knows all the good French writers and evaluates them competently.

He has some general knowledge of Italian and English literature and is

very well versed in that of Spain. . . . He is a lover of truth, heroism,

and honor and of the public interest and morality. He detests and scorns

all that is opposed to these lofty and noble sentiments. . . .

The General-in-Chief, Simón José Antonio Bolívar, will be forty-five years old on July 24 of this year [1828], but he appears older, and many judge him to be fifty. He is slim and of medium height; his arms, thighs, and legs are lean. He has a long head, wide between the temples, and a sharply pointed chin. A large, round, prominent forehead is furrowed with wrinkles that are very noticeable when his face is in repose, or in moments of bad humor and anger. His hair is crisp, bristly, quite abundant,

and partly gray. His eyes have lost the brightness of youth but preserve

the luster of genius. They are deep-set, neither small nor large; the eyebrows

are thick, separated, slightly arched, and are grayer than the hair on his

head. The nose is aquiline and well formed. He has prominent cheekbones,

with hollows beneath. His mouth is rather large, and the lower lip protrudes;

he has white teeth and an agreeable smile. . . . His tanned complexion

darkens when he is in a bad humor, and his whole appearance changes;

the wrinkles on his forehead and temples stand out much more prominently;

the eyes become smaller and narrower; the lower lip protrudes considerably,

and the mouth turns ugly. In fine, one sees a completely different countenance:

a frowning face that reveals sorrows, sad reflections, and sombre ideas. But

when he is happy all this disappears, his face lights up, his mouth smiles,

and the spirit of the Liberator shines over his countenance.

His Excellency

is clean-shaven at present. . . .

The Liberator has energy; he is capable of making a firm decision

and sticking to it. His ideas are never commonplace--always large, lofty,

and original. His manners are affable, having the tone of Europeans of

high society. He displays a republican simplicity and modesty, but he has

the pride of a noble and elevated soul, the dignity of his rank, and the

amour propre that comes from consciousness of worth and leads men to

great actions. Glory is his ambition, and his glory consists in having liberated

ten million persons and founded three republics. He has an enterprising

spirit, combined with great activity, quickness of speech, an infinite fertility

in ideas, and the constancy necessary for the realization of his projects.

Bolívar summarized his suggestions for forming new national governments in an important speech to the Congress of Angostura (Colombia), delivered on February 15, 1819. Notice his call for a strong central government more like the British parliamentary system than the federal approach of the United States. [Slatta comments appear in brackets.]

We have been ruled more by deceit than by force, and we have been degraded more by vice than by superstition. Slavery is the daughter of

darkness: an ignorant people is a blind instrument of its own destruction. Ambition and intrigue abuses the credulity and experience of men lacking all

political, economic, and civic knowledge; they adopt pure illusion as reality; they take license for liberty, treachery for patriotism, and vengeance for

justice. If a people, perverted by their training, succeed in achieving their liberty, they will soon lose it, for it would be of no avail to endeavor to explain

to them that happiness consists in the practice of virtue; that the rule of law is more powerful than the rule of tyrants, because, as the laws are more

inflexible, every one should submit to their beneficent austerity; that proper morals, and not force, are the bases of law; and that to practice justice is to

practice liberty.

Although those people [North Americans], so lacking in many respects, are unique in the history of mankind, it is a marvel, I repeat, that so weak and

complicated a government as the federal system has managed to govern them in the difficult and trying circumstances of their past. [Notice the Liberator's obvious distaste for North Americans and their "weak and complicated" government.] But, regardless of the

effectiveness of this form of government with respect to North America, I must say that it has never for a moment entered my mind to compare the

position and character of two states as dissimilar as the English-American and the Spanish-American. Would it not be most difficult to apply to Spain

the English system of political, civil, and religious liberty: Hence, it would be even more difficult to adapt to Venezuela the laws of North America.

Nothing in our fundamental laws would have to be altered were we to adopt a legislative power similar to that held by the British Parliament. Like the

North Americans, we have divided national representation into two chambers: that of Representatives and the Senate. The first is very wisely

constituted. It enjoys all its proper functions, and it requires no essential revision, because the Constitution, in creating it, gave it the form and powers

which the people deemed necessary in order that they might be legally and properly represented. If the Senate were hereditary rather than elective, it

would, in my opinion, be the basis, the tie, the very soul of our republic. [Bolívar's distrust of the rule of the non-white masses comes through clearly here. By making the Senate an inherited position, the creole elite minority could maintain its powerful over time.] In political storms this body would arrest the thunderbolts of the government

and would repel any violent popular reaction. Devoted to the government because of a natural interest in its own preservation, a hereditary senate would

always oppose any attempt on the part of the people to infringe upon the jurisdiction and authority of their magistrates. . .The creation of a hereditary

senate would in no way be a violation of political equality. I do not solicit the establishment of a nobility, for as a celebrated republican has said, that

would simultaneously destroy equality and liberty. What I propose is an office for which the candidates must prepare themselves, an office that demands

great knowledge and the ability to acquire such knowledge. All should not be left to chance and the outcome of elections. The people are more easily

deceived than is Nature perfected by art; and although these senators, it is true, would not be bred in an environment that is all virtue, it is equally true

that they would be raised in an atmosphere of enlightened education. [The educated creole minority would help tutor and guide the uneducated masses, too easily swayed by emotion or lack of knowledge.] The hereditary senate will also serve as a counterweight to both government and

people; and as a neutral power it will weaken the mutual attacks of these two eternally rival powers.

The British executive power possesses all the authority properly appertaining to a sovereign, but he is surrounded by a triple line of dams, barriers, and

stockades. He is the head of government, but his ministers and subordinates rely more upon law than upon his authority, as they are personally

responsible; and not even decrees of royal authority can exempt them from this responsibility. The executive is commander in chief of the army and

navy; he makes peace and declares war; but Parliament annually determines what sums are to be paid to these military forces. While the courts and

judges are dependent on the executive power, the laws originate in and are made by Parliament. Give Venezuela such an executive power in the person

of a president chosen by the people or their representatives, and you will have taken a great step toward national happiness. No matter what citizen

occupies this office, he will be aided by the Constitution, and therein being authorized to do good, he can do no harm, because his ministers will

cooperate with him only insofar as he abides by the law. If he attempts to infringe upon the law, his own ministers will desert him, thereby isolating him

from the Republic, and they will even bring charges against him in the Senate. The ministers, being responsible for any transgressions committed, will

actually govern, since they must account for their actions. [Notice that, although he suggests a very strong executive, Bolívar does believe in checks and balances.]

A republican magistrate is an individual set apart from society, charged with checking the impulse of the people toward license and the propensity of

judges and administrators toward abuse of the laws. He is directly subject to the legislative body, the senate, and the people: he is the one man who

resists the combined pressure of the opinions, interests, and passions of the social state and who, as Carnot states, does little more than struggle

constantly with the urge to dominate and the desire to escape domination. This weakness can only be corrected by a strongly rooted force. It should be

strongly proportioned to meet the resistance which the executive must expect from the legislature, from the judiciary, and from the people of a republic.

Unless the executive has easy access to all the administrative resources, fixed by a just distribution of powers, he inevitably becomes a nonentity or

abuses his authority. By this I mean that the result will be the death of the government, whose heirs are anarchy, usurpation, and tyranny. . . Therefore,

let the entire system of government be strengthened, and let the balance of power be drawn up in such a manner that it will be permanent and incapable

of decay because of its own tenuity. Precisely because no form of government is so weak as the democratic, its framework must be firmer, and its

institutions must be studied to determine their degree of stability...unless this is done, we will have to reckon with an ungovernable, tumultuous, and

anarchic society, not with a social order where happiness, peace, and justice prevail.

Unfortunately, history would unfold in Latin America much as Bolívar warned in his last paragraph above, as many forces destroyed any chance of democractic, stable governments in the newly independent Latin American nations. Just as not everyone agreed with Bolívar, not everyone agreed with

one another. Broadly speaking the creoles divided between liberal and conservative

elites.

Conservatives wanted only elite self-rule and freedom from Spain.

Beyond that they did not envision major changes from the "rules of the

game" under the colonial system. Conservatives generally believed in a

strong executive-- a monarch or a president for life. They distrusted the

masses and gave no thought to granting the unpropertied and uneducated

political power or legal equalty. Conservatives believed in a natural hierarchy

in which the rich and powerful enjoyed special legal priviledges (fueros)

not given to commoners. Thus military officers, clergy, merchants, and

other wealthy groups would enjoy special priviledges. Conservatives also

believed in the continued power, property, and influence of the Roman Catholic

Church. They tended to believe in monopoly economics, with key sectors

controlled by the few. In sum, conservatives pretty much wanted the old

colonial order to continue but without Spain. Bernardo O'Higgins in Chile

is a good example of a conservative politician.

Gerald E. Fitzgerald [Introduction to The Political Thought of Bolívar: Selected Writings The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1972, pp. 6-9] well summarized some of the Liberator's main political positions.