Yiddish Gauchos???

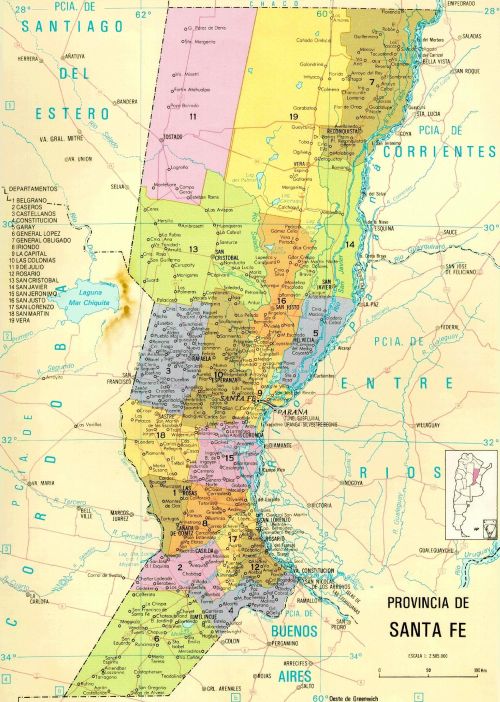

[You've read a lot about the gauchos of Argentina. Read the following documents and essays and comments and ask yourself, “how are these Yiddish or Jewish gauchos similar to and different from those described in Slatta, Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier?” Why might the concept of a “Jewish Gaucho,” which Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges termed an oxymoron, arise? These immigrants settled in Santa Fe Province. See map below.

For a full bibliography on Jews in Latin America, see Judith Laikin Elkin, editor and compiler, Recent Publications in Latin American Jewish Studies Current Bibliography,” published in Latin American Jewish Studies, Vol. 17:1, 17:2, 18:1, 18:2 (1997-1998)]

Document 1: Excerpts from The Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas by Alberto Gerchunoff [1883-1950] [This primary source, first appeared in Spanish in 1908, written by a Russian Jewish agricultural immigrant to Argentina. Part story, part memoir, it reveals the struggle of foreigners to retain their own cultural and religious identities while adapting to farm life in northern Argentina (Entre Ríos and Santa Fe provinces). He remembers his life as a young boy in the farming settlements of the late 1880s and early 1890s. This edition, translated by Prudencio de Pereda, first appeared in 1955. The University of New Mexico Press reissued the translation in paperback in 1998.]

[Rabbi Jehuda Anakroi, in Russia, before leaving for Argentina] “You'll see! You'll see! he said. “All of you! It's a country [Argentina] where everyone works the land where the Christians will not hate us, because there the sky is bright and clear, and under its light only mercy and justice can thrive” [p. 2]

“During the first years in the colonies of Entre Ríos [in the north of Argentina], the Jews knew very little abut the new homeland. Their conception of the Argentine people and customs was a confused one. They admired the Gaucho, and feared him, and they conceived of his life as a thrilling amalgam of heroism and barbarism [not unlike the views of Argentine President Domingo F. Sarmiento.] They had misinterpreted most of the gaucho tales of blood and bravery and, as a result, had formed a unique conception of their Argentine countryman. To the Jews of Poland and Bessarabia, the Gaucho seemed a romantic bandit, as fierce and gallant as any hero of a Schummer novel” [p. 11].

“The colonists did not know a word of Spanish. The young men had quickly taken up the dress and some of the manners of the Gauchos, but they could manage only the most basic Spanish phrases in their talk with the natives” [p. 12].

“We had to mark off a new field for plowing. We've hitched up the most docile oxen and placed the little red signal flag five hundred meters from the spot we start at—the place at which we are all standing now. We'll plow two furrows—one going toward the flag, one returning. Cutting the first furrows in a field is always a solemn occasions. Everybody realizes this [p. 27].

[criticism of a Jewish boy who adopted gaucho dress] “Oh, let that Gaucho be,” Doña Raquel cut in. “He has an answer for everything. Look at him! The complete Gaucho—those awful pants, the belt, the knife and even those little lead things to kill partridges with [bolas]. But, see him in the synagogue and he's quiet as a mouse. He doesn't even know his prayers. Imagine! Educated by my son, the Shochet, and he doesn't know how to pray [p. 38].

“It was still morning when the workers tied up the last sack of wheat. The threshing machine stopped, and the people went and sat in the shade of the unthreshed bundles and had coffee [what did real gauchos drink?]. a fierce sun was burning. It poured its heat over the dried countryside and gave it the gold-brown look of toast” [p. 45—question: is this an activity that a gaucho of Argentina would perform?].

“It's true, he said, “in Russia we lived badly, but there was the fear of God there and we lived according to the Law. Here, the young people are turning into Gauchos” [p. 46—question: what does is mean to turn into a gaucho?].

“His songs [Don Remigio, an old gaucho] were the old familiar décimas of the Gauchos—so called because they consisted of ten-line stanzas—songs that reflected the crude but pensive spirit of the Gaucho, that told of his valiant, barbarous spirit as well as the tenderness of his love. . . . A paladin with brave troops, he was ending his days in the ordinary, monotonous chores of a colony herdsman. Not even the rodeos of today were like the old ones—bursting with life and danger—and a man couldn't even indulge in a little bit of crime. The broad Pampas was divided into neat little farms now, bordered efficiently with wire fences and his spirit that nurtured itself in the communism of the lawless past was oppressed by this new cut-and-dried order and peace” [p. 67].

“The struggle was brief. Their daggers flashed as the two young men crouched, leaped in and then locked arms, jockeying for position. The stamp of their feet and their quick breathing were the only sounds as they broke again and then dodged and plunged with barbaric Gaucho skill” [p. 69—question: did this represent an unusual occurrence?].

“The Gaucho's eyes turned bright with anger, and what happened then happened instantly. Reb Saul [a Jewish farmer] saw him, but the Gaucho [Goyo] already had his knife out, and when the old man lifted the yoke to defend himself, Goyo pushed it aside with this left hand and, jumping forward, drove his knife deep into he old man's chest. Don Goyo walked out of the corral as if nothing had happened” [p. 73].

“They stopped before the gate, and were immediately surrounded by a barking, surging mass of dogs. Without thinking it strange for a Jew, Jacobo shouted out the typical greeting of the Pampas: “Hail Mary! Ave Maria." [p. 95].

Document 2: “A Century of Argentinean Jewry: In Search of a New Model of National Identity” by Efraim Zadoff

SUMMARY

The history of the Argentinean Jewish community dates back more than a century. The first organized group of Jewish immigrants to Argentina, Russian Jews, arrived in 1889 and established agricultural settlements. These were the famous Jewish gauchos. But the great majority of Jews who followed settled in Buenos Aires and in other large cities. Argentina was also a magnet for Jews from many parts of the Ottoman Empire and North Africa. Initially welcomed by government authorities, over time the Jews encountered an atmosphere that became to a certain degree, inhospitable. Still, the Jewish community, sub-divided by communal and even local origin, rapidly grew and built synagogues, schools, and other communal organizations that exist until the present day.

After the Holocaust, Argentina became one of the leading centers of Yiddish culture. However, after the birth of the State of Israel, Hebrew replaced Yiddish as the predominant language in Argentina's burgeoning system of Jewish education - a network of schools that today accounts for more half of all Jewish primary school pupils. In the 1950's the Argentinean Jewish community began to shrink in size. This process, largely caused by emigration, assimilation and a low fertility rate has continued. Over the last 40 years the number of Jews in Argentina has plummeted from over 300,000 to about 200,000.

Most Jews in Argentina, especially those of Ashkenazi origin, have generally sought a strictly secular model of Jewish identity, one that emphasizes a knowledge of Hebrew and Jewish history, as well as solidarity with the State of Israel. Today, with assimilation and inter-marriage on the rise, questions have been raised about the efficacy of this model in ensuring the future of the community.

Anti-Semitism remains a problem, but it has not impeded the Jewish community's overall development. However, in recent years financial criese have eroded the economic base of Argentinean Jews and their communal organizations, notably the celebrated day school network which is seen as the jewel in its crown

Document 3: “Argentina: The Land of the Jewish Gauchos” by Naomi Meyer

Argentina is a large country (3/10 the size of the United States). It borders on Chile, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil. Its total population is 37 million, most of whom are descendants of Spanish and Italian immigrants. The official language is Spanish. It won its independence from Spain in 1816.

The land of Argentina, the great pampas, is very fertile and some say that the best beef in the world comes from there. At one time, landowners were so wealthy that, when they traveled to their chateaux in Paris, they would take their own cows on the boat so that they could have fresh milk every day.

Many years ago, Argentina was home to the largest Jewish population in the Diaspora after the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and Buenos Aires was the fifth largest Jewish city outside of Israel. Today, its Jewish population is approximately 220,000, who live mainly in the capital, but are also spread out among the 23 provinces of the country. They comprise 2% of the total population.

The first Jews came to Argentina in the 1880s from Russia. The Jewish philanthropist Baron de Hirsch was their main sponsor. The Baron believed that, by buying them land there and helping them to form agricultural colonies, they would have a future of freedom from want and from religious persecution. It was not that simple. It took a long time and many hardships to enable them to endure and then later to succeed. They spoke Yiddish, built schools and synagogues and became the Jewish gauchos (cowboys). They formed settlements called “Moisesville,” [see Essay 2 below] “Claraville,” etc. (There's a documentary called “The Jewish Gauchos,” made by the daughter of the famous Argentine Yiddish writer and journalist Alberto Gerchunof.) Today, the colonies are practically empty. Most of the descendants of the original Jewish settlers have moved to the big cities, the large teacher's seminary has closed, and there are few Yiddish signs left in these areas.

Many more Jews joined the first immigrants to Argentina before and after the First World War, both from Europe and North Africa (Sephardic Jews). When Hitler came to power in the 1930's, Jews tried to escape from Germany. It was difficult to get into the U.S. and hard to go to Palestine, so that many Jews landed in the Caribbean countries and Latin America, hoping eventually to find their way to the U.S. But many stayed there, especially in Buenos Aires, the capital city. It is strange to think that a country known for its anti-Semitism and affiliation with Nazis was open for the Jews. Actually, the government saw an opportunity to increase the white, professional middle class population. Nazis were also let into the country during and after World War II.

Some said that the Nazis and the Jews came on the same boat, with the Nazis traveling first class and the Jews in steerage. In 1961, Adolph Eichmann, the infamous Nazi who devised the plan to exterminate Europe's Jews, was hunted down and caught by the Israeli secret police in a suburb of Buenos Aires. (There is also an exciting movie, “The House on Garibaldi Street,” about this story.) He was secretly taken out of the country and brought to Israel, where he was tried for war crimes and condemned to death.

The vast majority of the Jews who came to Argentina are Ashkenazi, that is, they came from central and eastern Europe. Argentinean Jews have held and continue to hold important positions in business, politics, the professions, and the arts.

The educational and cultural life of the Jews in Argentina has been rich. There are about 70 Jewish schools throughout the country. These institutions provided their students with both an outstanding secular and an exceptional Jewish education. Many of the students were able to speak fluent Hebrew (which is now helping those emigrating to Israel) and many studied for a semester or a year in Israel. Until the current financial crisis, many Jewish children studied in these schools. Now, many cannot afford the fees and so can no longer attend these schools.

[Jews, like other Argentines, have suffered political persecution.] The most infamous dictatorship was during the “Dirty War” between 1976 and 1983, when democracy was once again restored. The military government declared that they were cleansing the country to make it a Christian nation, free from corruption and free of dissidents. Their methods were to arrest, and, in most cases, torture, anyone whom they thought might be opposed to their ideas. Many people disappeared (30,000, including some 2000 Jews) and their bodies were never found Jacobo Timerman, a well-known Argentine Jewish journalist was arrested and tortured. After he was released, he wrote about his story in “Prisoner Without a Name and Cell Without a Number.” Rabbi Marshall T. Meyer*, an American-born rabbi who went with his wife to Argentina in 1959 and founded the Seminario Rabinico Latinoamericano for rabbis and teachers, became one of the most outspoken persons on human rights throughout this time, despite the danger to his own life.

After the military government's defeat, some of the perpetrators were put on trial and found guilty, but many were given amnesty by subsequent governments. Today, grandmothers still are searching for their grandchildren, who were born after their mothers were taken away and before they were killed. A few have been found.

In 1992, the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires was bombed and destroyed. Twenty-six people were killed. In 1994, the AMIA (The Central Organization of the Jewish Community) was bombed and destroyed with a death toll of 96 people, both Jews and non-Jews. While it is not clear who the actual perpetrators of these bombings were, a trial is now underway of 10 former Argentine police members thought to be involved in the AMIA attack. There is not much hope of positive results, either in the trial or in finding who was behind the bombings. Those looking into the bombings have focused on Iran, the Lebanese-based Hezbollah (Party of God), and members of the Buenos Aires provincial police as likely perpetrators.

In the last few years, the economic situation in Argentina has been deteriorating. In the past months, the country has totally collapsed financially. People have lost their life savings. Banks have restricted the amount that depositors are allowed to withdraw from their own accounts. Unemployment has risen to almost 30% and the number of people thrown into sudden poverty has been enormous.

This situation has been especially hard for the Jews, since most of the Jews belonged to the middle class (professionals, white-collar office workers, etc.), which has been totally impoverished. They are now called “the new poor.” Many people own their own homes, but can no longer afford to pay the electricity and gas bills. Many cannot even afford to pay for public transportation. Many are lacking food and must turn to the soup kitchens run by synagogues and other groups. This is a very tragic time for a country that once was a breadbasket for the world.

Document 4: Moises Ville, Santa Fe Province, Argentina” by Calvin Sims, New York Times News Service April 30, 1996

There are four synagogues in this remote farming town of 2,000 residents. The bakery sells Sabbath bread and cookies. Many buildings have Hebrew lettering and the Star of David on their facades. And children playing in the street use Yiddish words like "shlep'' and "shlock''. But there are only about 300 Jewish residents left in Moises Ville, an agricultural community founded by European Jews who came to Argentina a century ago, fleeing pogroms and other persecution in their homeland. While Jews once accounted for 90 percent of the population of Moises Ville, they now represent 15 percent and are rapidly declining, as most left the pampas decades ago seeking education and fortune in Argentina's big cities.

"This is one of the few places in the world where Jewish culture has remained dominant despite the fact that we are a small minority of the residents,'' said Ava Rosenthal, director of the town's museum. "No matter where you go in Moises Ville, it is very evident who was here first.''

Moises Ville, in fertile Santa Fe Province, [in the north-central part of Argentina] was the birthplace of a new breed of Argentine cowboy, the Jewish gauchos, who introduced new crops and started the country's first agrarian cooperatives. Jewish immigrants learned to ride, herd cattle, shoot and shelter themselves against the elements. They also maintained their own customs, building synagogues, libraries and cultural centers, including a Yiddish theater where groups from Europe and the United States performed.

Today, few if any Jewish gauchos ride the range, and most of the land surrounding Moises Ville and other Argentine Jewish communities has been sold to non-Jews, and gentiles do the farming on land still owned by Jews. But nowhere is the legacy of the Jewish gaucho so deeply entrenched as it is in Moises Ville, which still shuts down for Jewish holidays even though few residents celebrate them. The library is filled with volumes in Yiddish and Hebrew, and some elderly non-Jewish residents still remember prayers and blessings they learned as youths.

"Years after the last Jewish resident dies, the people of Moises Ville will still be eating gefilte fish and taking Yom Kippur as a holiday,'' said Pablo Trumper, 76, a retired schoolteacher whose grandfather was one of the original Jewish settlers.

Omar del Beno, Moises Ville's first non-Jewish mayor, said that although most residents are Roman Catholic, like the majority of Argentines, the town observes many Jewish cultural traditions because "they are what we grew up with and have become accustomed to.'' "We are such a close-knit community that people here don't even think about what's Jewish and what isn't,'' del Beno said. "We just live''. While Argentina is well known for having opened its doors to Nazis after World War II, at the turn of the century it welcomed large numbers of Jews, who formed colonies like Moises Ville in the interior of Argentina. Moises Ville was founded in 1889 by Russian Jews who were fleeing the pograms. With the help of a French philanthropist, the Jewish colonists bought land in Santa Fe Province and named their new settlement "town of Moses.''

Ana Weinstein, director of the Mark Turkow Center for Information and Documentation of Argentine Judaism, based in Buenos Aires, said that while gauchos taught the Jewish colonists how to survive in the wild and how to work the land, the settlers in turn introduced new crops like rice and sunflowers and Argentina's first farming cooperatives.

"Jews who founded Moises Ville and other agrarian colonies came from Russia and brought with them progressive socialist ideas that led them to establish agrarian cooperatives,'' Mrs. Weinstein said. "These were different from the Israeli kibbutz because here people didn't share the earnings of production in equal parts''. Instead, the colonists pooled their resources to buy seed and tools or to sell grain or cattle. But individuals earned according to their production, Mrs. Weinstein said.

Moises Ville's cooperative caught the attention of neighboring communities. In the Moises Ville museum, there are letters from nearby towns seeking information about the cooperative.

Today, Argentina has some 300,000 Jews, the largest population in Latin America. In recent years, after the bombing of Israeli Embassy and a Jewish cultural center in Buenos Aires, many Argentine Jews have started making annual pilgrimages to Moises Ville to celebrate their roots.

"Coming here is like going to Israel except it's a lot less expensive and much closer to home,'' said Pablo Barenboim, a pharmaceutical salesman, who drove seven hours from Buenos Aires to visit the town's museum and historic buildings. "I feel renewed and will definitely come back''. Martha Levisman de Clusellas, a renowned architect whose grandparents were among the founders of Moises Ville, said the town has always provided her with a sense of relief and comfort from Argentina's big cities, where she said there is anti-Semitism.

"For me Moises Ville is a place where I go to heal myself,'' she said. "It's like a treasure chest that once opened is unending because there is a part of us all in there''. But as Moises Ville's Jewish population dwindles, many worry that the traditions will not be maintained. Dr. Juan Kazneietz, director of the hospital, said that most Jewish residents are over 50 and that there is about one Jewish birth in Moises Ville only every three or four months. "Demographics are not on our side,'' Kazneietz said.

Indeed, only one of the town's four synagogues is open, and it has not had a full-time rabbi for years. Weekly services are often postponed because there is no quorum. The cemetery, which cannot be entered without the head covered in the Jewish tradition, has 5,000 graves. Students at the Jewish seminary say that while they feel pride being from Argentina's first Jewish settlement, they can't wait to graduate so they can go to college in bigger cities. "We've been taught all our lives that education is important and that we have to become professionals, but what opportunities are there here for us,'' said Diego Kanzepolsk, 17. Fanny Trumper, 92, who was born in Moises Ville, said she remembers a town "100 percent free'' of the anti-Semitism that she said exists in major cities of Argentina. "It was a beautiful experience growing up in a community where everyone was Jewish, the doctor, the lawyer, the mayor, and no one looked down on us because we were different,'' Mrs. Trumper said. "This is the most important place for Jews in Argentina, and we need to preserve it because it is the only one made entirely with Jewish hands.''

Document 5: “The Jewish Gaucho [in music]: Osvaldo Golijov makes it all come together” by Alan Rich

They're still talking about it in Stuttgart—about the night in the summer of 2000 when a capacity audience in that normally strait-laced metropolis went berserk for nearly half an hour at the world premiere of a 90-minute choral work from an unknown pen. "Was Madonna in the hall?" wondered one local paper. "Michael Jackson?" asked another. It was neither of the above, however: the music at hand bore the title The Passion According to St. Mark. Its composer was a slender, Argentine-born Jewish-American composer named Osvaldo Golijov (pronounced GO-lee-ov), who, he says, was just as exhilarated and astonished as anyone at the ovation in Stuttgart's spacious Liederhalle that night. So cherish the news that Passion is currently OC-bound—with virtually the same cast—as the not-to-be-missed high-decibel mark of the current Eclectic Orange Festival.

It's interesting enough that a composer raised in the tradition of Yiddishkeit in a backwoods enclave deep in the heart of Catholic Argentina would come to grips with a biblical happening best known among music people as inspiration for generations of German Lutheran composers. (Golijov says that when the commission came in, he had to run out and buy a copy of the New Testament.) For this, you can thank Helmuth Rilling, distinguished conductor of Bach and, more to the point, head of the Stuttgart-based International Bach Society.

It was Rilling who dreamed up the notion to dispatch four composers to create contemporary settings of the Passion narrative from the four Gospels to honor Bach, who himself had gotten around to completing only two, on the 250th anniversary of his death. All four settings—the others are by Tan Dun, Wolfgang Rihm and Sofia Gubaidulina—were performed in the summer of 2000. Three have already been released on the Haenssler label; Tan Dun's reworking of the St. Matthew text, complete with water percussion, is due out in November on Sony. Assume that all four composers took it upon themselves to unite the ancient texts and their awareness of what Bach had accomplished with the words of Matthew and John with their own worlds; by that assumption, the eclecticism of Golijov's own background is the force that kindles his amazing work. On the phone from his home outside Boston, where he teaches composition on several local faculties, he compared his own approach to the task with what Bach himself must have reasoned.

"His way was to take something in music that belonged to everyone—the Lutheran chorales that everybody sang in church—and create something transcendent around it," he says. "If he could take the DNA of his own world and translate it into his music of, say, 1730, I can do the same with the DNA of my own world. The only difference is that Bach's world was very narrow, and mine has been very wide."

And it's that breadth of focus that sends this Pasión Según San Marcos skyward: an extraordinary concoction in which the sublime sensibility of Bach gets stirred into the throb and exuberance of a Latino street festival. It grabs you, it holds you tight, and at the end—as the stricken Jesus filters into our sensibility to the throb of mambo rhythms while the Hebrew Kaddish sweeps over the ensemble as if from another world—you find yourself uplifted and drained. Golijov's score calls for orchestra and chorus, plus a wondrous array of Latino percussion. His chorus, in Stuttgart and on the recording, is the formidable Schola Cantorum of Carácas led by Maria Guinand, astounding in its ability to flip from neo-Baroque complexity to the full-throated outcry of a populace in pain. At Stuttgart and at a later reprise in Boston, a stage-filling dance and mime ensemble added to the wonderment; the whole indigenous ensemble comes together this year for a national tour, with Costa Mesa as the first stop. "Certain works have to define where you come from," Golijov says. "I come from a small Jewish colony surrounded by Catholic Argentina. Almost 100 years ago, a certain Baron Hirsch made it possible for a group of shetl Jews to escape persecution by the tsar and his Cossacks and set up farms in an unsettled region of Argentina. These “Gauchos Judeos,” as they were called—'Jewish gauchos'—never really assimilated. They held onto their Yiddishkeit, but they got along all right. My mother was a pianist, and she took me to Buenos Aires to hear opera and also to hear Astor Piazzolla's tangos. She sang to me in Yiddish, but she also got me to listen to Bach. Somehow, it all came together."

[Slatta note: As you can see, the term “Yiddish Gauchos” is not an accurate term historically or sociologically. Review chapters 10 and 11 of Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier which cover immigration from Europe and the mythologization of the gaucho. Notice that other immigrant groups as well as many writers, intellectuals, and politicians, used the gaucho as a political symbol. Why do you think Jewish immigrant farmers also tried to identify themselves with the gaucho?]