Cowboys of Brazil, 1902

Cowboys of Brazil, an excerpt from Rebellion in the Backlandsby Euclides da Cunha(1902)

[Compare these rural types who worked in the "hump" of northeastern Brazil during the late nineteenth-century with the gauchos of Argentina. The author uses some big words and some archaic words"don't worry about it. A positivist, like the "cientificos" of Mexico, note da Cunha's race-based views of the various cowboy types of Brazil.

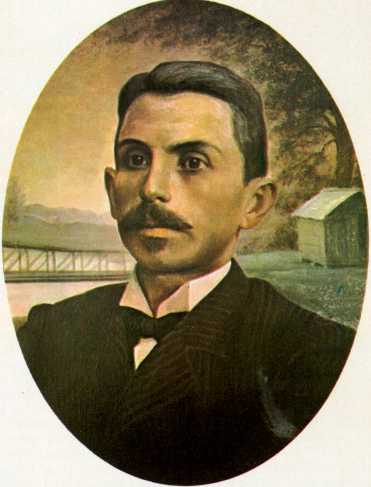

Born January 20, 1866, in Santa Rita do Rio Negro, Brazil, de Cunha died August 15, 1909, in Rio de Janeiro, shot during a personal quarrel. He wrote the classic historical narrative Os Sert§es (1902; Rebellion in the Backlands), in which he protested the treatment of forgotten inhabitants of Brazil's frontier, such as those described in the excerpt below.

Originally a military engineer, da Cunha left the army to become a civil engineer and later a journalist. As a reporter in 1896"97, he accompanied the Brazilian army to Canudos, a village in the backlands of Bahia state, in the northeast of the nation. A messianic leader named Ant˘nio Conselheiro ("the Counselor") and his followers had established their own "empire." After five successive expeditions, the government finally subdued the rebels, who resisted to the last man. His eyewitness account of the drama of rebellion and reprisal has the vividness of a novel. An amateur geographer, geologist, and an astute social observer, da Cunha left keen insights into the particular events and the larger significance of the inhospitable backlands and its rude inhabitants in the national life. In defiance of the common 19th-century pseudoscientific belief in the inferiority of mixed races (a theme that haunts Brazilian literature), da Cunha concludes with a strongly worded plea that the republic commit itself to assimilating its backward countrymen into the mainstream of Brazilian life. Every August Brazilians observe a "Euclides Week" in his honor. [Portrait of Euclides da Cunha]THE SERTANEJO

The sertanejo, or man of the backlands [the dry plains area of northeastern Brazil, the "hump" that sticks out into the Atlantic Ocean], is above all else a strong individual. He does not exhibit the debilitating rachitic tendencies of the neurasthenic mestizos [mixed European and Indian] of the seaboard. His appearance, it is true, at first glance, would lead one to think that this was not the case. He does not have the flawless features, the graceful bearing, the correct build of the athlete. He is ugly, awkward, stooped. Hercules-Quasimodo reflects in his bearing the typical unprepossessing attributes of the weak. His unsteady, slightly swaying, sinuous gait conveys the impression of loose-jointedness. His normally downtrodden mien is aggravated by a dour look which gives him an air of depressing humility. On foot, when not walking, he is invariably to be found leaning against the first doorpost or wall that he encounters. While on horseback, if he reins in his mount to exchange a couple of words with an acquaintance, he braces himself on one stirrup and rests his weight against the saddle. When walking, even at a rapid pace, he does not go forward steadily in a straight line but reels swiftly, as if he were following the geometric outlines of the meandering backland trails. And if in the course of his walk he pauses for the most commonplace of reasons, to roll a cigarro, strike a light, or chat with a friend, he falls""falls" is the word"into a squatting position and will remain for a long time in this unstable state of equilibrium, with the entire weight of his body suspended on his great-toes, as he sits there on his heels with a simplicity that is at once ridiculous and delightful. He is the man who is always tired. He displays this invincible sluggishness, this muscular atony, in everything that he does: in his slowness of speech, his forced gestures, his unsteady gait, the languorous cadence of his ditties"in brief, in his constant tendency to immobility and rest.

Yet all this apparent weariness is an illusion. Nothing is more surprising than to see the sertanejo's listlessness disappear all of a sudden. In this weakened organism complete transformations are effected in a few seconds. All that is needed is some incident that demands the release of slumbering energies. The fellow is transfigured. He straightens up, becomes a new man, with new lines in his posture and bearing; his head held high now, above his massive shoulders; his gaze straightforward and unflinching.

Through an instantaneous discharge of nervous energy, he at once corrects all the faults that come from the habitual relaxation of his organs; and the awkward rustic unexpectedly assumes the dominating aspect of a powerful, copper-hued Titan, an amazingly different being, capable of extraordinary feats of strength and agility.

This contrast becomes evident upon the most superficial examination. It is one that is revealed at every moment, in all the smallest details of back-country life"marked always by an impressive alternation between the extremes of impulse and prolonged periods of apathy.

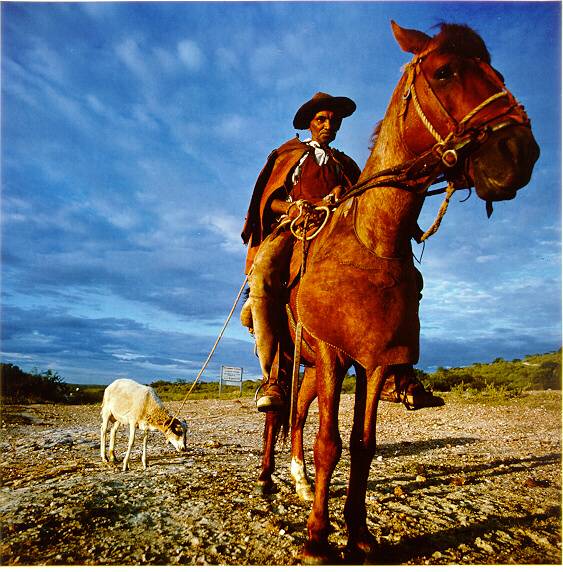

It is impossible to imagine a more inelegant, ungainly horseman: no carriage, legs glued to the belly of his mount, hunched forward and swaying to the gait of the unshod, mistreated backland ponies, which are sturdy animals and remarkably swift. In this gloomy, indolent posture the lazy cowboy will ride along, over the plains, behind his slow-paced herd, almost transforming his "nag" into the lulling hammock in which he spends two-thirds of his existence. But let some giddy steer up ahead stray into the tangled scrub of the caatinga, or let one of the herd at a distance become entrammeled in the foliage, and he is at once a different being and, digging his broad-roweled spurs into the flanks of his mount, he is off like a dart and plunges at top speed into the labyrinth of jurema thickets. Let us watch him at this barbarous steeple chase.Nothing can stop him in his onward rush. Gullies, stone heaps, brush piles, thorny thickets, or riverbanks"nothing can halt his pursuit of the straying steer, for wherever the cow goes, there the cowboy and his horse go too. Glued to his horse's back, with his knees dug into its flanks until horse and rider appear to be one, he gives the bizarre impression of a crude sort of centaur: emerging unexpectedly into a clearing, plunging into the tall weeds, leaping ditches and swamps, taking the small hills in his stride, crashing swiftly through the prickly briar patches, and galloping at full speed over the expanse of tablelands.

His robust constitution shows itself at such a moment to best advantage. It is as if the sturdy rider were lending vigor to the frail pony, sustaining it by his improvised reins of caroa fiber [also carod, a sword-sharp cactus], suspending it by his spurs, hurling it onward"springing quickly into the stirrups, legs drawn up, knees well forward and close to the horse's side""hot on the trail" of the wayward steer; now bending agilely to avoid a bough that threatens to brush him from the saddle; now leaping off quickly like an acrobat, clinging to his horse's mane, to avert collision with a stump sighted at the last moment; then back in the saddle again at a bound"and all the time galloping, galloping, through all obstacles, balancing in his right hand, without ever losing it once, never once dropping it in the liana thickets, the long, iron-pointed, leather-headed goad which in itself, in any other hands, would constitute a serious obstacle to progress. But once the fracas is over and the unruly steer restored to the herd, the cowboy once more lolls back in the saddle, once more an inert and unprepossessing individual, swaying to his pony's slow gait, with all the disheartening appearance of a languishing invalid.Disparate Types: The Jagunšo and the Ga˙cho

The southern ga˙cho [of Rio Grande do Sul, the Brazilian state just north of Uruguay], upon meeting the vaqueiro at this moment, would look him over commiseratingly. The northern cowboy is his very antithesis. In the matter of bearing, gesture, mode of speech, character, and habits there is no comparing the two. The former, denizen of the boundless plains, who spends his days in galloping over the pampas, and who finds his environment friendly and fascinating, has, assuredly, a more chivalrous and attractive mien.

He does not know the horrors of the drought and those cruel combats with the dry-parched earth. His life is not saddened by periodic scenes of devastation and misery, the grievous sight of a calcined and absolutely impoverished soil, drained dry by the burning suns of the Equator. In his hours of peace and happiness he is not preoccupied with a future which is always a threatening one, rendering his happiness short lived and fleeting. He awakes to life amid a glowing, animating wealth of Nature; and he goes through life adventurous, jovial, eloquent of speech, valiant, and swaggering; he looks upon labor as a diversion which affords him the sport of stampedes; lord of the distances is he, as he rides the broad level-lying pasture lands, while at his shoulders, like a gaily fluttering pennant, is the inevitable scarf, or pala.

The clothes that he wears are holiday garb compared to the vaqueiro's rustic garments. His wide breeches are cut to facilitate his movements astride his hard-galloping or wildly rearing bronco [As in Argentina called a bagual, an unbroken horse, one that can be controlled only by the lasso] and are not torn by the ripping thorns of the caatingas. Nor is his jaunty poncho ever lost by being caught on the boughs of the crooked trees. Tearing like an unleashed whirlwind across the trails, clad in large russet-colored boots with glittering silver spurs, a bright-red silk scarf at his neck, on his head his broad sombrero with its napping brim, a gleaming pistol and dagger in the girdle about his waist"so accoutered, he is a conquering hero, merry and bold. His horse, inseparable companion of his romantic life, is a near-luxurious object, with its complicated and spectacular trappings. A ragged ga˙cho on a well-appareled pingo [horse] is a fitting sight, in perfectly good form, and, without feeling the least out of place, may ride through the town in festive mood.

THE GA┌CHO

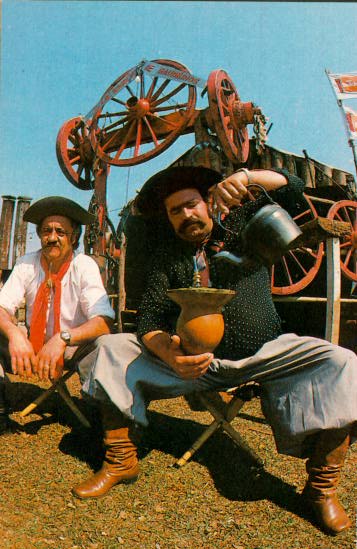

The ga˙cho, valiant "cowpuncher" that he is, is surely without an equal when it comes to any warlike undertaking. To the shrill and vibrant sound of trumpets, he will gallop across the pampas, the butt of his lance firmly couched in his stirrup; like a madman, he will plunge into the thick of the fight; with a shout of triumph, he is swallowed up from sight in the swirl of combat, where nothing is to be seen but the flashing of sword on sword; transforming his horse into a projectile, he will rout squadrons and trample his adversaries, or"he will fall in the struggle which he entered with so supreme a disregard for his life. [Gauúchos of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, enjoying mate -- giant size.]THE JAGUNăO

The jagunšo is less theatrically heroic; he is more tenacious; he holds out better; he is stronger and more dangerous, made of sterner stuff. He rarely assumes this romantic and vainglorious pose. Rather, he seeks out his adversary with the firm purpose of destroying him by whatever means he may. He is accustomed to prolonged and obscure conflicts, without any expansive display of enthusiasm. His life is one long arduously achieved conquest in the course of his daily task. He does not indulge in the slightest muscular contraction, the slightest expenditure of nervous i energy, without being certain of the result. He coldly calculates his enemy. At dagger-play he does no feinting. In aiming the long rifle or the heavy irabuco, [a type of catapult gun] he "sleeps upon the sights."

Should his missile fail to reach its mark and his enemy not fall, the gaucho, beaten or done in, is a very weak individual in the grip of a situation in which he is placed at a disadvantage or of the outcome of which he is uncertain. This is not the case with the jagunco. He bides his time. He is a demon when it comes to leading his enemy on; and the latter has before him, from this hour forth, sighting him down his musket barrel, a man who hates him with an inextinguishable hatred and who lies hidden there in the shade of the thicket.

THE VAQUEIRO

The vaqueiro, on the other hand, grew up under conditions the opposite of these, amid a seldom varying alternation of good times and bad, of abundance and want; and over his head hung the year-round threat of the sun, bringing with it in the course of the seasons repeated periods of devastation and misfortune. It was amid such a succession of catastrophes that his youth was spent. He grew to manhood almost without ever having been a child; what should have been the merry hours of childhood were embittered by the specter of the backland droughts, and soon enough he had to face the tormented existence that awaited him. He was one damned to life. He understood well enough that he was engaged in a conflict that knew no truce, one that imperiously demanded of him the utilization of every last drop of his energies. And so he became strong, expert, resigned, and practical. He was fitting himself for the struggle.

His appearance at first sight makes one think, vaguely, of some ancient warrior weary of the fray. His clothes are a suit of armor. Clad in his tanned leather doublet, made of goatskin or cowhide, in a leather vest, and in skintight leggings of the same material that come up to his crotch and which are fitted with knee pads, and with his hands and feet protected by his calfskin gloves and shinguards, he presents the crude aspect of some medieval knight who has strayed into modem times.

This armor of his, however, reddish-gray in hue, as if it were made of flexible bronze; does not give off any scintillations; it does not gleam when the sun's rays strike it. It is dead and dusty-looking, as befits a warrior who brings back no victories from the fight.

His homemade saddle is an imitation of the one used in the Rio Grande region but is shorter and hollowed out, without the luxurious trappings of the other. Its accessories consist of a weatherproof goatskin blanket covering the animal's haunches, of a breast covering, or pectorals, and of pads attached to the mount's knees. This equipment of man and beast is adapted to the environment. Without it, they would not be able to gallop through the caatingas and over the beds of jagged rock in safety.

Nothing, to tell the truth, is more monotonous and ugly than this highly original garb of one color only, the russet-gray of tanned leather, without the slightest variation, without so much as a strip or band of any other hue. Only at rare intervals, when a "shindig" is held to the strains of the guitar, and the backwoodsman relaxes from his long hours of toil, does he add a touch of novelty to his appearance in the form of a striking vest made of jungle cat or puma skin with the spots turned out"or else he may stick a bright red bromelia in his leather cap. This, however, is no more than a passing incident and occurs but rarely.

Once the hours of merrymaking are over, the sertanejo loses his bold and frolicsome air. Not long before he had been letting himself go in the dance, the sapateado [From sapata, "a shoe"; the dance, as indicated, being marked by the clacking of shoes or sandals], as the sharp clack of sandals on the ground mingled with the jingling of spurs and the tinkling of tambourine bells, to the vibrant rhythms, the "rip-snortings" of the guitars; but now once more he falls back into his old habitual posture, loutish, awkward, gawky, exhibiting at the same time a strange lack of nervous energy and an extraordinary degree of fatigue. Now, nothing is more easily to be explained than this permanent state of contrast between extreme manifestations of strength and agility and prolonged intervals of apathy.

A perfect reflection of the physical forces at work about him, the man of the northern backlands has served an arduous apprenticeship in the school of adversity, and he has quickly learned to face his troubles squarely and to react to them promptly. He goes through life ambushed on all sides by sudden, incomprehensible surprises on the part of Nature, and he never knows a moment's respite. He is a combatant who all the year round is weakened and exhausted, and all the year round is strong and daring, preparing himself always for an encounter in which he will not be the victor, but in which he will not let himself be vanquished; passing from a maximum of repose to a maximum of movement, from his comfortable, slothful hammock to the hard saddle, to dart, like a streak of lightning, along the narrow trails in search of his herds.

His contradictory appearance, accordingly, is a reflection of Nature herself in this region"passive before the play of the elements and passing without perceptible transition from one season to another, from a major exuberance to the penury of the parched desert, beneath the refracted glow of blazing suns. He is as inconstant as Nature. And it is natural that he should be. To live is to adapt one's self. And she has fashioned him in her own likeness: barbarous, impetuous, abrupt.

These contrasting characteristics are prominent in normal times. Thus, every sertanejo is a vaqueiro. Aside from the rudimentary agriculture of the bottom plantations on the edge of the rivers, for the growing of those cereals which are a prime necessity, cattle-breeding is in these parts the kind of labor that is least unsuited to the inhabitants and to the soil. On these backland ranches, however, one does not meet with the festive bustle of the southern estancias [ranches].

"Making the roundup" [hacer rodeo in Spanish] is for the gaucho a daily festival, of which the showy cavalcades on special occasions are little more than an elaboration. Within the narrow confines of the mango groves or out on the open plain, cowpunchers, foremen, and peons may be seen rounding up the herd, through the brooks and gullies, pursuing intractable steers, lassoing the wild pony, or felling the rearing bull with the boleador, as if they were playing a game of rings; their movements are executed with incredible swiftness, and they all gallop after one another, yelling lustily at the top of their lungs and creating a great tumult, as if having the best time in the world. In the course of their less strenuous labors, on the other hand, when they come to brand the cattle, treating their wounds, leading away those destined for the slaughter, separating the tame steers, and picking out the broncos condemned to the horsebreaker's spurs"at times like these, the same fire that heats the branding iron provides the embers with which to prepare the roast, cooked with the skin on, for their rude feasts, or serves to boil the water for their strong and bitter-tasting Paraguayan tea, or mate. And so their days go by, well filled and varied.UNCONSCIOUS SERVITUDE

The same thing does not happen in the north. Unlike the estancieiro [rancher of southern Brazil], the fazendeiro [ranch owner of the northeastern backlands] lives on the seaboard, at a distance from his extensive properties, which he sometimes never sees. He is heir to an old historic vice. Like the landed proprietor of colonial days, he parasitically enjoys the revenues from vast domains without fixed boundaries, and the cowboys are his submissive servants. As the result of a contract in accordance with which they receive a certain percentage of what is produced, the latter remain attached to the same plot of ground; they are born, they live and die, these beings whom no one ever hears of, lost to sight in the backland trails and their poverty-stricken huts; and they spend their entire lives in faithfully caring for herds that do not belong to them. Their real employer, an absentee one, well knows how loyal they are and does not oversee them; at best, he barely knows their names.

Clad, then, in their characteristic leathern garb, the sertanejos throw up their cottages, built of thatch and wooden stakes, on the very edge of the water pits, as rapidly as if they were pitching tents, and enter with resignation upon a servitude that holds out no attractions for them. The first thing that they do is to learn the ABC's, all that there is to be known, of an art in which they end by becoming past masters"that of being able to distinguish the "irons" of their own and neighboring ranches. This is the term applied to all the various signs, markings, letters, capriciously wrought initials, and the like which are branded with fire on the animal's haunches, and which are supplemented by small notches cut in its ears. By this branding the ownership of the steer is established. He may break through boundaries and roam at will, but he bears an indelible imprint which will restore him to the solta to which he belongs. [A solta is an unenclosed pasture, sometimes at quite a distance from the farmhouse. When nearer at hand and situated in pleasant surroundings, they bear the special name of the herd(logrador).]

For the cowboy is not content with knowing by heart the brands of his own ranch; he learns those of other ranches as well; and sometimes, by an extraordinary feat of memory, he comes to know, one by one, not only the animals that are in his charge but those of his neighbors also, along with their genealogy, characteristic habits, their names, ages, etc. Accordingly, should a strange animal, but one whose brand be knows, show up in his logrador, he will restore it promptly. Otherwise, he will keep the intruder and care for it as he does for the others, but he will not take it to the annual fair, nor will he use it for any labor, for it does not belong to him; he will let it die of old age.

When a cow gives birth to a calf, he brands the latter with the same private mark, displaying a perfection of artistry in doing so; and he will repeat the process with all its descendants. One out of every four calves he sets aside as his own; that is his pay. He has the same understanding with his boss, whom he does not know, that he has with his neighbor, and, without judges or witnesses, he adheres strictly to this unusual contract, which no one has worded or drawn up.

It often happens that, after long years, he will succeed in deciphering i the brand on a strayed bullock, and the fortunate owner will then receive, in place of the single animal that had wandered from his herd, and which he has long since forgotten, all the progeny for which it has been responsible. This seems fantastic, but it is nonetheless a well-known fact in the backlands. We mention it as a fascinating illustration of the probity of these backwoodsmen. The great landed proprietors, the owners of the herds, know it well. They all have the same partnership agreement with the vaqueiro, summed up in the single clause which gives him, in exchange for the care that he bestows upon the herd, one-fourth of the products of the ranch; and they are assured that he will never filch on the percentage.

The settlement of accounts is made at the end of winter and ordinarily takes place without the presence of the party who is chiefly interested. That is a formality that may be dispensed with. The vaqueiro will scrupulously separate the large majority of the new cattle (on which he puts the brand of the ranch) as belonging to the boss, while keeping for himself only the one out of every four that falls to him by lot. These he will brand with his own private mark, and will either keep them or sell them. He writes to the boss, giving him a minute account of everything that has happened on the place, going into the most trivial details; and then he will get on with his never interrupted task. That task, although on occasion it can be tiring enough, is an extremely rudimentary one. There does not exist in the north a cattle-raising industry. The herds live and multiply in haphazard fashion. Branded in June, the new steers proceed to lose themselves in the caatingas along with the rest.

Here their ranks are thinned by intense epizootic infections, chief among them rengue, a form of lameness, and the disease known as the mal triste [leperous affliction, a type of hydrophobia]. The cowboys are able to do little to halt the ravages of these affections, their activities being confined to riding the long, endless trails. Should the herd develop an epidemic of worms, they know a better specific than mercury: prayer. The cowboy does not need to see the suffering animal. It is enough for him to turn his face in its direction and say a prayer, tracing on the ground as he does so a maze of cabalistic lines. And, what is more amazing still, he will cure it by some such means as this.