Persecution by the Chilean Military, Academic Freedom in Chile and the US

[Abridged from interview with Raleigh News and Observer staff Dec. 12, 2003; print verion appeared in the N&O, Sunday December 14, 2003]

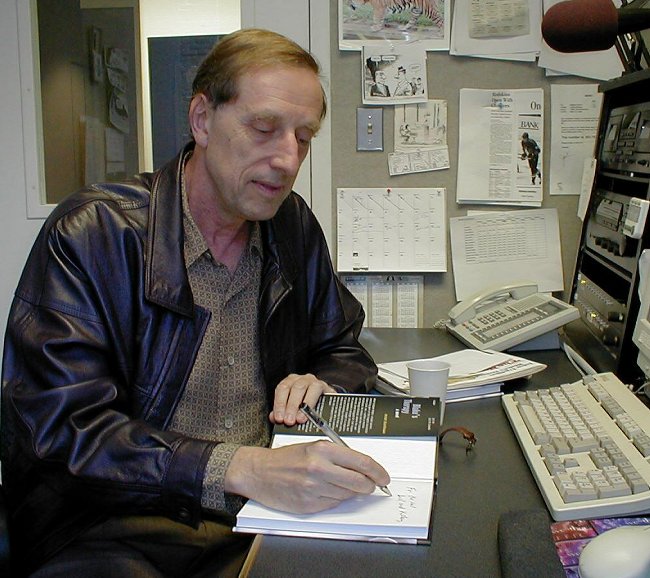

[Interview with Ariel Dorfman, distinguished professor of literature and Latin American studies at Duke University, is a member of the academic freedom committee of the international group Human Rights Watch. You also wish to listen to the audio track from another interview with Dorfman on WUNC radio's "The Connection," that aired in September 2002.The N&O: When you talk about academic freedom, how do you define it? Ariel Dorfman: It's primarily a form of freedom that has taken humanity many centuries to establish as necessary to the well-being of all society, and it means that particularly within the boundaries of the university -- though also outside it -- all members of the community are free of pressure and of persecution for their ideas. I see it as primarily an invitation to be critical and not to pay the consequences for that in any way, shape or form.

I come from an experience where academic freedom has been suppressed very brutally -- I'm speaking of Chile in my case. In Latin America in general, it has been a tradition that persecution is a tradition, and colleagues of mine have been tortured, killed and exiled, and certainly thrown out of the university. I had a tenured chair at 29 at the University of Chile, and after the 1973 coup, I was thrown out of my job for subverting students. But that was nothing compared to the fact that they were looking to kill me for my writings and my political activity. Because I've been through that in Chile, where we had more university autonomy than you have here, I worry. The law said that the police couldn't even come into the campus without permission. It was a way of defending dissidence, given the brutality with which professors, students and intellectuals had been treated habitually in our societies. So we were way ahead of you on the point of academic freedom. Before the 1973 coup, we could say anything we wanted. And I witnessed terrible things happening in a place that was democratic, that had total freedom of research and speech. After the military takeover, thousands of students and professors were removed, many were killed, and in my case they stole my pension and my salary -- punishment, in fact, for speaking exactly the way I am speaking to you now. I said to myself: This can't happen here. But it can, and I would not want this country to have a dictatorship like the one in Chile. To control a society, you must control how they think. To free a society, one must allow people to think on their own. If there are excesses, they should be corrected by the university community itself, not by people foreign to that body. . . . The N&O: What has changed over that time? Dorfman: If you had called before 9/11, 2001, I probably would have said, “No, speak to somebody else.” But the reason I am giving this interview is because I feel that in the United States academic freedom is in danger, and this danger relates directly to the fear that has been created in this country by those acts of terror and by the ways in which people in power today are using those fears to suppress or at least limit the Bill of Rights. This assault on academic freedom is small compared to a place like Iran or China, let's say. But it's increasingly significant compared to places like Germany, England or Sweden. Or democratic Chile today, for that matter.

When a society becomes fearful, terrible things are often done in the name of security. Very often what academics do in their intellectual explorations is to render the mind insecure -- capable of questioning reality, questioning the way in which things are established, to question power. If you look at the history of intellectual thought, that is how humanity meditates about its condition, that's how we progress, that is the way in which we think and feel ourselves out of crisis. We have an inalienable right as academics to make the world feel less secure about its convictions, and that helps us to be more secure in the long-term safety of the republic. There are many signs that are disturbing since 9/11. The N&O: Such as? Dorfman: Let me bring up the most disturbing of all because of its far-reaching consequences and because it is being voted on very soon. Title VI legislation has been providing funding for international programs in higher education since the 1950s. It was created as a way in which, given the alarm caused by Sputnik and the fact that the United States was becoming involved in many foreign lands it knew little about, to fund major research and also aid in the professional development of students who would be able to work in international areas and languages. The United States has been dreadfully provincial in that sense and continues to be, but less so than in the 1950s. So it was seen as a way in which the United States could fund a series of projects dedicated to all different areas of the world that allowed academics to study, and also train students. It comes up for refunding every six years, and one of the things in the original law was a sense that the government was not to interfere in any way in what was being taught in these institutions or offered as courses. House Resolution 3077 has been approved and sent to the Senate, where an amendment proposes to create an International Education Advisory Board -- the members of this board would come from the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Defense and the National Security Agency -- now I'm going to quote, “to increase accountability by providing advice, counsel and recommendations to Congress on international education issues for higher education.” The fundamental problem here is that this is a form of interference and censorship of what can be taught; it is a way in which government will be able to control how these funds are used and penalize those who may disagree with it. What really worries me is the idea that many of these studies, according to those who propose this legislation, have become quote-unquote anti-American, and therefore the idea is that the government should only be funding those things that the advisory board deems to be American. Pluralism or one truth? The N&O: You make it sound like the McCarthy era in the 1950s. Dorfman: Precisely. What is of increasing concern is that we have a situation where one group defines what America is, and everything outside that in academic terms could be understood to be quote-unquote fostering terrorism. And you need to put that sort of definition of who is the enemy of America in the present political context of the Patriot Act, etc. This sort of legislation is very troubling. America has to decide whether it stands for pluralism or it stands for one truth only. Because intellectual dissent as such is essential to intellectual inquiry, it would be imposing very stringent limits on what is legitimate and what is understood as subversive. This turns into a form of control. And that is frightening because it determines ahead of time who is and who is not right, and neither this government nor any other one, of whatever political stripe, has any business deciding this. I'm not naive enough to suppose that the government does not influence what is studied, just like the corporations influence what is studied and what is not. There will always be a tension between what academics, professors, scientists want to research and what the powers outside would prefer. This influence is probably inevitable, but we have to be vigilant and build a buffer against intervention, and legislation of this sort would weaken enormously these buffers, if not abolish them. I would be less worried if this were not part of the assault on the Bill of Rights by the government, the excesses of the Patriot Act. It's really a question of what is anti-American, and I could argue quite cogently, I hope, that those who are proposing this legislation are anti-American, if you define America, as I do, as a place of tolerance that welcomes dissent and understands its security as being enhanced by a critical knowledge of the rest of the world. There's a big discussion about the lack of quote-unquote intelligence regarding Iraq and terrorism. That sort of intelligence is very often determined by what the people who are in power decide they want to hear. That is why we are now in such a dreadful situation in Iraq, which threatens to create problems for many years to come. The question is, [is] this the moment when we should be getting rid of intelligence in the intellectual sense of critical inquiry? In other words, are we basically creating laws to become more stupid? I know this sounds like a joke, but I'm dead serious because this anti-academic atmosphere, where those who think differently are blamed for the weakness of America, will determine in great measure how this country thinks for itself. The United States has been at the forefront in the last 50 years of many of the planet's discoveries and discussions because it has been able to foster a climate of freedom. It's not an unlimited climate of freedom; there are limits, of course. The N&O: Just how free should professors be? Dorfman: We should be totally free as long as we do not engage in any crime. If I go into a classroom and shoot somebody, I can't claim to be expressing myself academically. But I would defend the right of others to say and write whatever they believe, even if it is frowned upon in general society. There are statements I find deplorable, like Nazi propaganda and people denying the Holocaust or callers on a radio show telling me it's great that [Chilean President] Salvador Allende was killed just like Martin Luther King, but I do not want to limit what those persons say. My answer is, “I am sorry you feel that way, but you have the right to say it,” because I don't want anybody telling me that I don't have the right to say that the United States is carrying out a foreign policy, and an ecological plundering policy, which could destroy this planet. . . . There has been a closing down of the American mind, and it worries me. If a pro-Palestinian person comes to speak, you have to have a pro-Israeli person. That's not the way to foster debate. The debate does not always occur in television terms, which is you against me. The debate occurs in people's minds, it's ongoing, and what you learn from one person you apply to question the next one. I often feel that we lack confidence in the capability of our professors and our students to figure out the truth by themselves by dedicating themselves to study. To attain the sovereignty of the intellect has taken our species a long time. Think of why exile has been such a major factor in the development of science and the humanities, especially in the 20th century, and why so many of the great minds of history have written and done their research in exile. Isn't it because they were exiled in some sense in their countries first, leading many of them to migrate to the United States? It could be argued that large numbers of the major wonders of the mind and of science of the second half of the 20th century were produced by those emigres from Europe, especially Germany. Albert Einstein is the best example. You don't want your Einsteins to go somewhere else where there is freedom for them to think whatever they want. Surely, this nation is great enough to accept dissidence not as something to be tolerated, but as something to be encouraged and subsidized. . . . And what I see happening in the last couple of years, after the Sept. 11 attacks, is that the role of the public intellectual has become more primary and contestatory; therefore, you will find more academics engaged in debate, dissension and discussion than before. It was always happening, but it overflows out of the university more than before, turning the university [into] a center of discussion and contention. The boundaries between society and university become more porous. It is in this context that I regard David Horowitz's suggestions disturbing when he asks students to find out the political affiliation of professors, to try to balance this so universities look more like the country. I don't use the word fascist easily, but this is fascist in the sense of corporate fascism. The idea that a university should represent the general population and its trends makes no sense whatsoever. The N&O: Why not? Dorfman: If that had been the case in the Middle Ages, everybody would have voted that the Earth was flat. Critical inquiry, science, cannot be dependent upon electoral politics. If we start witch hunts, it destroys the autonomy of intellectual inquiry. Just as I don't want for my opponents to say that I don't belong in the university because I don't represent the general population, I would not want one of my opponents to be expelled from the university in a sort of Stalinist coup because they disagree with what I think. Especially, you don't want students determining politically who they should study with. I tell my students, “Look, what you get from me, you probably won't get from most other professors, and that's good. I urge you to find those with whom you disagree and then compare and make up your own minds.” We don't have to agree about intellectual matters at all. The gun behind the eye The N&O: Anything to add? Dorfman: I would like to emphasize how important it is for Americans to think about the world because that world has come into American lives with a vengeance, and one would like to ask why there is such a vengeance. The more we know, the better we will be. Isn't that obvious? That knowledge emerges out of conflicting opinions, searches, quests and doubt. Precisely because it's a time when it is proclaimed that to have doubts is to be anti-patriotic, I would say that the most patriotic thing you can do today is to doubt. That doesn't mean you should not be very firm in your fight against criminal violence on a massive scale. I'm not saying that. But we find ourselves at a moment of discussion about what these fundamental values mean, and the fate of the world is in great measure in the hands of the American people, and so much power is very dangerous if it is not accompanied by wisdom. And part of that wisdom does come from people who have spent most of their lives thinking deeply about the world, about history, about literature, about language, about text, about law, about morality. There's an anti-intellectual strain in American history, and this strain could very well get worse. Since Sept. 11, assaults on intellectual autonomy have multiplied, reminding us of the early 1950s and the late 1960s. Again, these were moments of crisis, moments when it was deemed that national security was at stake. There are many examples of intolerance, fear of what is foreign: for instance, the restrictions on foreign student visas or professors who cannot attend conferences in the United States. Cuban professors could not come to our Latin American studies meeting, an Indonesian land-reform activist who was invited to spend a semester at the University of California at Berkeley couldn't come, and I could go on and on with many examples. After Sept. 11, many parents called in to protest when UNC professors organized a forum. It's absurd to protest a university doing what universities should do: make people think differently, open us all up to positions we might otherwise not hear. For more information, visit Ariel Dorfman's Home Page.