Cowboys In Life and Legend

for NCCAT Seminar, June 2005

by Richard W. Slatta

material reprinted from The Cowboy Encyclopedia

1994 by ABC-CLIO ** 1996 W. W. Norton

- Introduction

- Race

- Work Life

- Conflicting Views of the Cowboy

- Dress and Equipment

- Social Realities

- Economic Realities

- Primary Sources and Memoirs about Cowboy Life

- Ride Back to the Cowboys Life and Legend Home Page

Etymologists trace the use of the term cowboy back to 1000

AD in Ireland. Swift used it in 1705, logically enough, to

describe a boy who tends cows. Modern usage, first in hyphenated

form, dates from the 1830s in Texas. Colonel John S. "Rip" Ford

used the word cow-boy to describe the Texan border raider who

drove off Mexican cattle during the 1830s. The term carried a

tinge of wildness, of life at the fringes of law and

"civilization."

Etymologists trace the use of the term cowboy back to 1000

AD in Ireland. Swift used it in 1705, logically enough, to

describe a boy who tends cows. Modern usage, first in hyphenated

form, dates from the 1830s in Texas. Colonel John S. "Rip" Ford

used the word cow-boy to describe the Texan border raider who

drove off Mexican cattle during the 1830s. The term carried a

tinge of wildness, of life at the fringes of law and

"civilization."  RACE: Unlike most movie depictions, not all cowboys were white.

Racial distribution varied from place-to-place. Mostly Anglo

cowboys worked the Montana ranges. Further south, however, in

Texas, for example, perhaps one-third of the hands may have been

African-Americans or Mexican-Americans.

RACE: Unlike most movie depictions, not all cowboys were white.

Racial distribution varied from place-to-place. Mostly Anglo

cowboys worked the Montana ranges. Further south, however, in

Texas, for example, perhaps one-third of the hands may have been

African-Americans or Mexican-Americans.

VIEWS OF THE COWBOY: The cowboy generated conflicting appraisals. When observed

at the end of a long trail drive, "hellin' 'round town," cowboys

attracted little praise. The Topeka Commonwealth (August 15,

1871), painted an unflattering portrait of the cowboy on a tear.

VIEWS OF THE COWBOY: The cowboy generated conflicting appraisals. When observed

at the end of a long trail drive, "hellin' 'round town," cowboys

attracted little praise. The Topeka Commonwealth (August 15,

1871), painted an unflattering portrait of the cowboy on a tear.

The Texas cattle herder is a character, the like of which can be found nowhere else on earth. Of course he is unlearned and illiterate, with but few wants and meager ambition. His diet is principally navy plug and whiskey and the occupation dearest to his heart is gambling. His dress consists of a flannel shirt with a handkerchief encircling his neck, butternut pants and a pair of long boots, in which are always the legs of his pants. His head is covered by a sombrero, which is a Mexican hat with a high crown and a brim of enormous dimensions. He generally wears a revolver on each side of his person, which he will use with as little hesitation on a man as on a wild animal. Such a character is dangerous and desperate and each one has generally killed his man.The unsympathetic writer went on to catalog the cowboy's additional sins of swearing, fighting, and aversion to authority.

It is possible that there is not a wilder or more lawless set of men in any country that pretends to be civilized than the gangs of semi-nomads that live in some of our frontier States and Territories and are referred to in our dispatches as "the cowboy boys." Many of them have emigrated from our States in order to escape the penalty of their crimes, and it is extremely doubtful whether there is one in their number who is not guilty of a penitentiary offense, while most of them merit the gallows. They are supposed to be herdsmen employed to watch vast herds of cattle, but they might more properly be known under any name that means desperate criminal. They roam about in sparsely settled villages with revolvers, pistols and knives in their belts, attacking every peaceable citizen met with. Now and then they take part in a dance, the sound of the music frequently being deadened by the crack of their pistols, and the hoe-down only being interrupted long enough to drag out the dead and wounded.

Out in the Territories there are only two classes--the "cowboys" and the "tenderfeet." Such of the "cowboys" as are not professional thieves, murderers and miscellaneous blacklegs who fled to the frontier for reasons that require no explanation, are men who totally disregard all of the amenities of Eastern civilization, brook no restraint, and--fearing neither God, nor man or the devil--yielding allegiance to no law save their own untamed passions. He is the best man who can draw the quickest and kill the surest. A "cowboy" who has not killed his man--or to put it more correctly his score of "tenderfeet"--is without character standing, or respect. The "tenderfoot" who goes among them should first double his life insurance and then be sure he is "well-heeled."

We deem it hardly necessary to say in the next place that the cowboy is a fearless animal. A man wanting in courage would be as much out of place in a cow-camp, as a fish would be on dry land. Indeed the life he is daily compelled to lead calls for the existence of the highest degree of cool calculating courage. As a natural consequence of this courage, he is not quarrelsome or a bully. As another necessary consequence to possessing true manly courage, the cowboy is as chivalrous as the famed knights of old. Rough he may be, and it may be that he is not a master in ball room etiquette, but no set of men have loftier reverence for women and no set of men would risk more in the defense of their person or their honor. Another and most notable of his characteristics is his entire devotion to the interests of his employer. We are certain no more faithful employee ever breathed than he; and when we assert that he is, par excellence, a model in this respect, we know that we will be sustained by every man who has had experience in this matter.

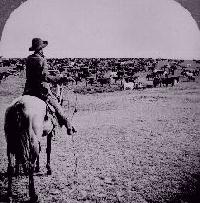

How can we account for such sharply conflicting visions of

cowboy character? First, where the writer observed cowboys is

important. Those who saw hands sweating at work on the range,

riding, roping, and branding, remarked their strength, skill,

courage, and hard work. Likewise, writers who saw cowboys in

town, letting off steam after months on the trail or range, saw

only lawlessness and debauchery in the cowboy's life. The few

journalists who actually spent time on the range with working

cowhands formed a positive view.

How can we account for such sharply conflicting visions of

cowboy character? First, where the writer observed cowboys is

important. Those who saw hands sweating at work on the range,

riding, roping, and branding, remarked their strength, skill,

courage, and hard work. Likewise, writers who saw cowboys in

town, letting off steam after months on the trail or range, saw

only lawlessness and debauchery in the cowboy's life. The few

journalists who actually spent time on the range with working

cowhands formed a positive view.

He lives hard, works hard, has but few comforts and fewer necessities. He has but little, if any, taste for reading. He enjoys a coarse practical joke or a smutty story; loves danger but abhors labor of the common kind; never tires riding, never wants to walk, no matter how short the distance he desires to go. He would rather fight with pistols than pray; loves tobacco, liquor and women better than any other trinity. His life borders nearly upon that of an Indian. If he reads anything, it is in most cases a blood and thunder story of a sensational style. He enjoys his pipe, and relishes a practical joke on his comrades, or a corrupt tale, wherein abounds much vulgarity and animal propensity.

A cowboy undresses upward: boots off, then socks, pants, and shirt. He never goes deeper than that. After he has removed the top layer he takes his hat off and lays his boots on the brim, so the hat won't blow away during the night. Spurs are never taken off boots. In the morning a cowboy begins dressing downward. First he puts on his hat, then his shirt, and takes out of his shirt pocket his Bull Durham and cigarette papers and rolls one to start the day. He finishes dressing by putting on his pants, socks, and boots. This is a habit that usually stays with a cowboy long after his days in the saddle are over.