Bonaire History

by Richard W. Slatta

Bonaire is a chunk of limestone, coral, and a little sand sitting about 50 miles off Venezuela's northern coast. Smack in the trade wind belt, it enjoys steady winds from the east that temper the otherwise hot and dry climate. Its closest island neighbors are Curacao and Aruba, discovered by the Spanish, but later taken over and settled by the Dutch.

Precolumbian populations, notably the Caiquetios, left their mark on Bonaire. One can view Precolumbians drawings, such as that at the right. These drawings exist on a limestone shelf, now about 200 yards inland. This shelf was once the island's shoreline until falling ocean water levels left it high and dry. The Caiquetios, Arawaks, probably arrived from Venezuela about 1000 CE. These original inhabitants may have been quite tall, as the Spaniards dubbed these leeward islands "the islands of giants." Alonso de Ojeda and Amerigo Vespucci became the first Europeans to visit Bonaire in 1499. They claimed it for Spain, but Bonaire attracted little attention for a long while. Barren, windy, with little productive soil and low rainfall, it held few attractions. Finding little of productive value, Spaniards had largely depopulated the island by 1515. They hunted Indians and transported them to work on sugar plantations on Hispaņola. About a decade later, Spaniards colonized and began raising cattle. Governor Juan de Ampues imported laborers (Caiquetios) and livestock, including cows, shepp, goasts, pigs, doneys, and horses, mostly raised for their hides. In 1634, the Dutch occupied neighboring Curacao and two years later took over Bonaire. The Dutch recognized the strategic importance of the island --and soon found an important resource to exploit-- salt, he key resource for food preservation required technology. In 1639, The Dutch West India Company initiated salt production, along with stock raising and corn growing.

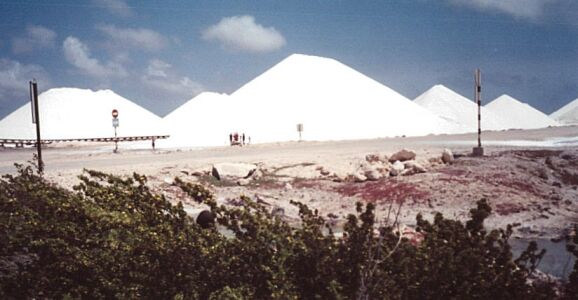

With the help of modern technologies, salt production, mostly for commerical,

not table use, revived during the 1950s. Now large machines do the labor--not

slaves. Bonaire exports large quantities of salt, and much of the southern

portion of the island is devoted to its production. Petroleum storage and

transfer began in 1975. Since 1986, the island has become a major rice producer.

The Antillean Rice Mills produces enought for local consumption aas well

as export, under brand

With the help of modern technologies, salt production, mostly for commerical,

not table use, revived during the 1950s. Now large machines do the labor--not

slaves. Bonaire exports large quantities of salt, and much of the southern

portion of the island is devoted to its production. Petroleum storage and

transfer began in 1975. Since 1986, the island has become a major rice producer.

The Antillean Rice Mills produces enought for local consumption aas well

as export, under brand  names

including "Blue Ribbon," "Comet," "Chop Sticks," and a natural brown rice

called "Wild Flamingo Rice." Since the creation of the Marine Park in 1971,

however, tourism has became by far the most important part of Bonaire's

economy. By banning spear fishing and other destructive practices, island

officials have created an underwater paradise. Diving,

snorkeling (less attractive since the coral destruction of a 1999 storm),

and the rugged, impressive scenery attract visitors from around the world.

Wind surfers enjoy excellent conditions in shallow Lac Bay, on the island's

windy east side. Tourism has also prompted islanders to be multilingual.

Most speak Papiamento, a local dialect, as well as Dutch, Spanish, English,

and sometimes French. Impressive!

names

including "Blue Ribbon," "Comet," "Chop Sticks," and a natural brown rice

called "Wild Flamingo Rice." Since the creation of the Marine Park in 1971,

however, tourism has became by far the most important part of Bonaire's

economy. By banning spear fishing and other destructive practices, island

officials have created an underwater paradise. Diving,

snorkeling (less attractive since the coral destruction of a 1999 storm),

and the rugged, impressive scenery attract visitors from around the world.

Wind surfers enjoy excellent conditions in shallow Lac Bay, on the island's

windy east side. Tourism has also prompted islanders to be multilingual.

Most speak Papiamento, a local dialect, as well as Dutch, Spanish, English,

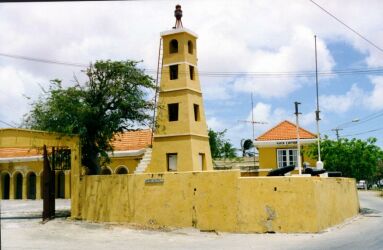

and sometimes French. Impressive!  The Dutch built the small Fort Oranje near the harbor in the capital city

of Kralendijk to protect their possession. The original wood fort, built

in 1639, stood armed with four cannons--never fired in anger. In 1868, officials

added a a wooden tower in the mid-19th, replaced by the present stone lighthouse

in 1932, the date that a disastrous hurricane struck the island. The fort

is painted the mustard color typical of Dutch colonial architecture in the

Caribbean.

The Dutch built the small Fort Oranje near the harbor in the capital city

of Kralendijk to protect their possession. The original wood fort, built

in 1639, stood armed with four cannons--never fired in anger. In 1868, officials

added a a wooden tower in the mid-19th, replaced by the present stone lighthouse

in 1932, the date that a disastrous hurricane struck the island. The fort

is painted the mustard color typical of Dutch colonial architecture in the

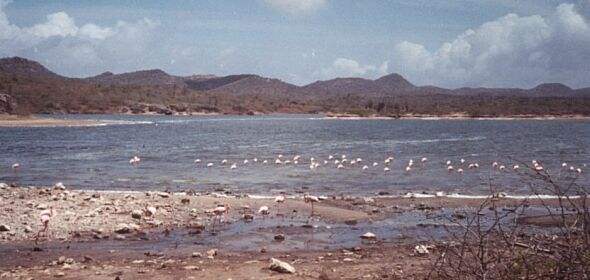

Caribbean.  The island's flamingo population had once dwindled to 1500 birds. Thanks

to aggressive conservation measnures, some 35-40,000 pink Caribbean flamingos

now nest in the salt flats and salinas (salty lakes) around the island.

Another 200 bird species inhabit the island, making it a birder's paradise.

Bring your binoculars! Thus the island's intelligent environmental laws

protect both land and marine life. Other programs protect sea turtles. A

Donkey Sanctuary, located near the airport, offers protection to these hardy

work animals, many of which still roam freely about the island. Much of

the island wild life can be viewed at Washington-Slagbaai National Park,

a 13,500 acre refuge on the island's north end. Created in 1969, the preserve

expanded with the addition of a second planation a decade later. The rough

roads permit a slow, measured driving pace, so that one can view donkeys,

a variety of birds, including the colorful lora or Bonairean parrot, iguanas

and small lizards, divi divi trees, and impressive vistas on all sides.

In many places, the cacti forest is virtually imprenetrable. Originally

two plantations, they produced cattle, goals, aloe, salt, and charcoal.

The latter, produced by burning mesquite and other trees, contributed to

the decline of forest, mostly replaced by thick growths of tall cacti. The

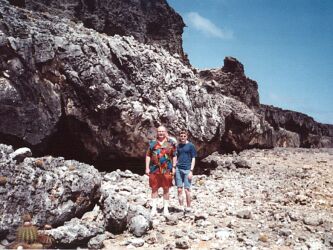

area now awes visitors with its jagged limestone ridge (the original island

shore), blow holes, rugged hills (highest point Brandaris Hill at 790 feet),

azure waters and crashing waves. For more online information, visit

Bonaire.org. On the island, check out the history museum and the visitor's

bureau for more information. Alas, we could not find a single book on the

island's history written in English.

The island's flamingo population had once dwindled to 1500 birds. Thanks

to aggressive conservation measnures, some 35-40,000 pink Caribbean flamingos

now nest in the salt flats and salinas (salty lakes) around the island.

Another 200 bird species inhabit the island, making it a birder's paradise.

Bring your binoculars! Thus the island's intelligent environmental laws

protect both land and marine life. Other programs protect sea turtles. A

Donkey Sanctuary, located near the airport, offers protection to these hardy

work animals, many of which still roam freely about the island. Much of

the island wild life can be viewed at Washington-Slagbaai National Park,

a 13,500 acre refuge on the island's north end. Created in 1969, the preserve

expanded with the addition of a second planation a decade later. The rough

roads permit a slow, measured driving pace, so that one can view donkeys,

a variety of birds, including the colorful lora or Bonairean parrot, iguanas

and small lizards, divi divi trees, and impressive vistas on all sides.

In many places, the cacti forest is virtually imprenetrable. Originally

two plantations, they produced cattle, goals, aloe, salt, and charcoal.

The latter, produced by burning mesquite and other trees, contributed to

the decline of forest, mostly replaced by thick growths of tall cacti. The

area now awes visitors with its jagged limestone ridge (the original island

shore), blow holes, rugged hills (highest point Brandaris Hill at 790 feet),

azure waters and crashing waves. For more online information, visit

Bonaire.org. On the island, check out the history museum and the visitor's

bureau for more information. Alas, we could not find a single book on the

island's history written in English.