19th-Century Conflicts Continued

White Masters versus African Slaves

Columbus and other explorers brought African slaves with them on the earliest journeys of exploration in the New World. Black colonists helped Nicolás de Ovando form the first Spanish settlement on Hispaniola [today the Caribbean island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic] in 1502. Between 1502 and 1518, Spain shipped out hundreds of Spanish-born Africans, called Ladinos, to labor in the New World, especially in the mines. Nuflo de Olano, a black slave, accompanied Vasco Núñez de Balboa when he sighted the Pacific Ocean from Panama in 1513. Other blacks served with Hernán Cortés in the 1520s when he conquered Mexico and with Francisco Pizarro when he marched into Peru a decade later. An African named Estebanico survived Pánfilo de Narváez's unfortunate expedition to Florida in 1527. With three companions, he spent eight years traveling overland all the way to Mexico City. He learned several Native American languages in the process. Later, on another expedition in what is now New Mexico, he lost his life in a dispute with the Zuni.

During the slave trade era, circa 1500-1850, some 12 million Africans began the trans-Atlantic voyage, and more than 10 million arrived. The Atlantic slave trade involved the largest intercontinental migration of people in world history prior to the 20th century Roughly 40 percent of the total went to the Caribbean islands; another 38 percent went to Brazil; and Spanish America accounted for 17 percent. Only about 6 percent, 400,000 Africans, entered what would become the United States. Lacking immunities to European diseases, Native Americans died in massive epidemics. Africans came from an environment where those who survived into adolescence acquired some immunity to such "Old World" diseases as smallpox, mumps, and measles, as well as to such tropical maladies as malaria and yellow fever.

On average, 16 percent of the men, women, and children involved perished in transit, although mortality on some voyages could be much higher. “Close-packed” ships crammed Africans together like sardines in a can, accepting a relatively high mortality rate as the price of business. “Loose packing” gave individuals slightly more room, in hopes of getting a higher percentage of them to the New World alive. The typical ocean crossing might last from 25 to 60 days, depending on origin, destination, and winds. Slaves remained below at night on decks four or five feet high. They had less than half the space allotted convicts or soldiers transported by ship at the same time. Captains kept groups of slaves above deck through as much of the day as weather permitted. Men remained shackled; women and children were freer; crews encouraged movement and activity. Two meals included corn and rice from the less-forested regions on the northern and southern extremes; yams from the Niger delta to the Zaire River. Sometimes dried beans from Europe were standard fare. Each person received about a pint or less of water with a meal.

A Portuguese physician, Luiz Antonio de Oliveira Mendes, published his observations of treatment before and during the “Middle Passage” from Africa across the Atlantic. He served aboard a slave ship in 1793. “When they are first traded, they are made to bear the brand mark of the backlander who enslaves them, so that they can be recognized in case they run away. When they reach a port, they are branded on the right breast with the coat of arms of the king and nation. This mark is made with a hot silver instrument. They are made to bear one more brand mark. This one is ordered by their private master, and is either put on the left breast or on the arm, so that they may be recognized if they should run away.”

“Shackled in the holds of ships, the black slaves reveal as never before their robust and powerful qualities, for in these new circumstances they are far more deprived than when on land. First of all, with two or three hundred slaves placed under the deck, there ishardly room enough to draws a breath. No air can reach them, except through the hatch gratings. . . . Twice a week they [officers] order the deck washed, and , using sponges, the hold is scoured down with vinegar. Convinced that they are doing something useful, each day they order a certain number of slaves brought on deck in chains to get some fresh air, not allowing more because of their fear of rebellion. However, very little is accomplished in this way, because the slaves must go down again into the hold to breathe the same pestilent air.

“Second, the slaves are afflicted with a very short ration of water, of poor quality and lukewarm because of the climate—hardly enough to water their mouths. The suffering that this causes is extraordinary, and their dryness and thirst cause epidemics which, beginning with one person, soon spread to many others. Thus, after only a few days at sea, they start to throw the slaves into the ocean. Third, they are kept

“Third, they are kept in a state of constant hunger. Their small ration of food, brought over from Brazil on the outward voyage, is spoiled and damaged, and consists of nothing more than beans, corn, and manioc flour, all badly prepared and unspiced. They add to each ratio a small portion of noxious fish from the African coast, which decays during the voyage.”

Slavery is, of course, much older than the Atlantic slave trade. Sumerians in Mesopotamia relied on slave labor before 3000 BC, as did the ancient Egyptians. China had slavery during the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), and the societies of classical Greece and Rome made heavy use of slave labor from the 6th century BC through the 5th century AD. Most societies in sub-Saharan Africa also used captives and dependents for labor. The Atlantic slave trade, however, greatly jumped the demand for labor as plantations spread throughout the Western Hemisphere. Most plantations produced sugarcane for Europe, but planters eventually grew such other products as coffee, cocoa, rice, indigo, tobacco, and cotton.

The Atlantic slave trade became an integral part of an international trading system. The Atlantic slave trade became part of a prosperous trading cycle known as the triangular trade. In the first leg of the triangle, European merchants purchased African slaves with commodities manufactured in Europe or imported from European colonies in Asia. They then sold the slaves in the Caribbean and purchased such easily transportable commodities as sugar, cotton, and tobacco. Finally the merchants would sell these goods in Europe and North America. They would use the profits from these sales to purchase more goods to trade in Africa, continuing the trading cycle.

However, as the following section indicates, elites found ways other than slavery to control the lives and labor of Latin America's non-white masses. You will explore a case study of how elites did so in Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier.

END Masters and Slaves

Gauchos of Argentina: Elites Oppressing Masses

Let's start with a Gaucho Photo Gallery for a quick look at this fascinating historical figure. Although most of the images are contemporary, you'll see that much gaucho equipment and dress remains largely unchanged since the 19th century. The Spanish conquistadores and their Portuguese counterparts brought many elements of European culture to Latin America. On Columbus's second voyage in 1493-94, for example, he brought horses and cattle to the Caribbean.

Extending out from the Caribbean, livestock raising became a major economic activity in many grasslands regions of North and South America. In northern Mexico and California, Roman Catholic missions played an important role in speading ranching and in teaching Indians to work as cowboys. Horsemen of the Americas originally hunted vast herds of wild cattle and horses for their hides. These horsemen developed unique equestrian subcultures that blended indigenous and European elements.

Let's start with a Gaucho Photo Gallery for a quick look at this fascinating historical figure. Although most of the images are contemporary, you'll see that much gaucho equipment and dress remains largely unchanged since the 19th century. The Spanish conquistadores and their Portuguese counterparts brought many elements of European culture to Latin America. On Columbus's second voyage in 1493-94, for example, he brought horses and cattle to the Caribbean.

Extending out from the Caribbean, livestock raising became a major economic activity in many grasslands regions of North and South America. In northern Mexico and California, Roman Catholic missions played an important role in speading ranching and in teaching Indians to work as cowboys. Horsemen of the Americas originally hunted vast herds of wild cattle and horses for their hides. These horsemen developed unique equestrian subcultures that blended indigenous and European elements.

Research note on Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier I hope that you enjoy learning about gauchos. I had a great time during the year I spent researching the gauchos book in Argentina. When I got off the bus in the small town of Tandil, to research in local archives, I had only walked a block when a man grabbed my elbow. The next day I was front-page news in the local paper. The newspaper editor spotted an obvious gringo in town and sensed that this could be news. The fact that I had arrived from the US to study the gaucho, Argentina's national hero, made me a local hero. Local historians and ranchers sought me out as I worked at the archives. The third day I attended an all-day gaucho fiesta. It's like a pig picking but with beef cooked over an open fire (asado). And yes, you do spent hours drinking a variety of beverages and conversing, as the meat cooks. So, like the gauchos you read about, I worked hard, had some difficuties (Argentina suffered until military dictatorship then), but also enjoyed life. A few years later I returned as an invited lecturer to Tandil and got to see my old friends again (and ate more asado). I also arranged for the publication of a Spanish edition of the book. It made it to Argentina's best seller list for a few weeks and got dozens of reviews (mostly positive). However, most reviews included a sort of "left-handed" compliment. "Even though this guy is a gringo, he still seems to know lots about our gaucho." But cowboys exist elsewhere in Latin America as well.

On the tropical plains of Colombia and Venezuela arose sturdy

riders called llaneros. They worked cattle in a hostile environment

that alternated between flooding monsoon rains and extended periods

of drought. In Mexico, vaqueros worked cattle on ranches and

missions. Brazil developed two major ranching traditions: that of the

vaqueiro in the northeast hump and the gaucho (with an accent over the u) subculture

in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. In Argentina and Uruguay

arose wild-cattle hunters who came to be called gauchos.

[The map to the right shows the pampas, the vast, grassy plain where the gauchos of Argentina and Uruguay, as well as the similar gauchos of southern Brazil, rode. Compare the varieties of Brazilian cowboys

described in 1902 by Brazilian writer Euclides da Cunha.

[The map to the right shows the pampas, the vast, grassy plain where the gauchos of Argentina and Uruguay, as well as the similar gauchos of southern Brazil, rode. Compare the varieties of Brazilian cowboys

described in 1902 by Brazilian writer Euclides da Cunha.

Gauchos, like cowboys everywhere, developed their own peculiar language, equipment,

and dress. From the Indians of pampa (plains) came a fondness for mate, a caffeine-rich herbal tea still enjoyed throughout southern South America. Gauchos also adopted the

bolas or boleadoras, a weapon long used by Indians. The Spanish, of course, contributed the horse, cattle, and a long equestrian tradition that exalted "the man on horseback."

Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier covers only one kind of gaucho, who lived in Buenos Aires province, Argentina. Gaucho culture and dress varied somewhat from province to province. The gauchos of the northern province of Salta, for example, are distinguished by their bright red ponchos. We have have a book from Argentina titled "The Yiddish Gauchos." Did Jewish gauchos really exist? Check this article about Yiddish gauchos to find out.

Gauchos remain an important part of the national cultures of Argentina and Uruguay. See information about an opera based on gaucho life. It's performed in Buenos Aires. The Matadero street fair also provides a look at gaucho life.

Writing in the mid-1860s, Wilfred Latham aptly described the gaucho of the time: "He rarely knows any other food than beef, asado [quick-roasted beef], with or without salt; his luxuries are mate, Paraguay tea, sucked through a tube from a gourd, and cigarettes. Born to the horse, as it were, the gaucho is a splendid horseman, dexterous with the lasso. In full career after a wild bull or cow, he swings the lasso and throws it unerringly over the animal's horns; then on his checking the horse, the lasso, which is fastened to a ring in the broad hide girth of the saddle, is drawn taut, and

the animal swung round or thrown."

The quotation above is what historians call a "primary source." The term means a document or other piece of evidence that orginated at the time and place under study. Primary sources, firsthand accounts, are the lifeblood of history. In your own essays, you should quote from primary sources whenever possible to support your interpretation. Secondary sources, such as the Gauchos book you are reading, are written after-the-fact. Good secondary sources are based mostly on primary sources. Fortunately, we have a rich collection of documents dating back to the 1500s [see your primary documents page.]

During much of the 1600s and 1700s, gauchos rode the plains killing wild cattle

for their hides. With wild livestock in such great abundance, few worried

about exhausting such an enormous resource. By the mid-1700s, however,

estancieros, landowning ranchers, began to lay claim to the land

and its resources. Able to control government policy, the increasingly

rich and powerful ranchers manipulated the law in their favor and against

the rural poor--the gauchos. Gauchos could be drafted into the military

to form blandengue units to fight Indians on the frontier. Lands

gained from the Indians, however, went to the landed elite or the government--not

to gauchos.

[Humorous aside: Argentine artist Florencio Molina Campos painted comical, but apt portraits of gauchos. In the picture below, we see a gaucho using the bolas or boleadoras, stones attached to long leather thongs. Unfortunately, he, like Charles Darwin on his visit to the pampas, has caught his own horse (see Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier).]

Charles Darwin visited the pampa in the early 1830s, a critical period in Argentine political life. Darwin recorded his impressions of gaucho character and appearance in his Journal of Researches (1839):

At night we stopped at a pulperia, or drinking-shop. During the evening a great number of Gauchos came in to drink spirits and smoke cigars: their appearance is very striking; they are generally tall and handsome, but with a proud and dissolute expression of countenance. They frequently wear their mustaches and long black hair curling down their backs. With their brightly-coloured garments, great spurs clanking about their heels, and knives stuck as daggers (and often so used) at their waists, they look a very different race of men from what might be expected from their name of Gauchos, or simple countrymen. Their politeness is excessive: they never drink their spirits without expecting you to taste it; but whilst making their exceedingly graceful bow, they seem quite as ready, if occasion offered, to cut your throat. [from "Gauchos" in The Cowboy Encyclopedia and Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier]

By the early 1800s, ranchers began processing dried meat for export

to Brazil and Cuba. This jerky (charqui) made cattle more valuable and

further increased the rancher desire to control land, water, animals, and

grass on the pampa. Gauchos did not share the rancher's private property

ethic, and conflicts arose. Over time, gauchos had to change their way of life from wild cattle hunting on the open range to branding the cattle of the land owners who oppressed them. Indeed, as the late distinguished historian E. Bradford Burns has written, elite-mass

confict forms a major motif in 19th-century Latin American history. This

conflict resulted in "the victory of the European-oriented ruling elites

over the Latitn American folk with their community values." (Burns, The

Poverty of Progress, Univ. of California Press, 1980, p. 1).

As you read about the values, characteristics, and attitudes of the gaucho, contrast

them with the views of the ranching elite and with the Enlightenment-inspired liberals of the 19th century. You may locate many of the places discussed in the Gauchos book on this map of Buenos Aires Province and surroundings. You can also compare the gaucho's life during the 19th century, as presented in Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier, with firsthand observations made in the early 1940s by Francis Herron, a young student visiting from the US, Letters from the Argentine.

END Gauchos

Men versus Women: Gendered Conflict [A Neverending Story??]

"Women are from Venus, Men are from Mars" goes the pop wisdom mantra

of the 1990s. There is little question that, historically speaking, women

and men have been assigned significantly different roles in most societies.

The trend toward legal and social equality for women are a relatively recent

phenemenon.

To gauge your understanding of gender issues, try to determine whether each of the following items is determined by Sex (S) or Gender (G). Sex differences are biologically based. They stem from biological differences between men and women [review high school anatomy notes]. Gender differences are socially and culturally defined. Societies or groups within a society define what is appropriate, proper, fitting behavior for men and women and thus create different gender roles. Such socially defined differences vary widely in different time periods, cultures, and even regions. As historian Karen Anderson has written, gender describes "those cultural and historical processes that operated to create, represent, and reproduce differences between men and women."

Ask yourself whether each of the following statements or assumptions is based on Sex (biology) or Gender (social definitions).

1. ______ Women bear children.

2. ______ Only men can fight in wars.

3. ______ Men are naturally better at logic and math than women.

4. ______ The husband is the natural head of the household.

5. ______ Women are better at simple, repetitive manual labor.

6. ______ Men are more prone to heart attacks than women.

7. ______ Women are more emotional than men.

8. ______ Men handle money more wisely than women.

9. ______ Women are morally superior to men.

10.______ The maternal instinct makes women better at raising and caring for children.

Men and women do differ biologically (duh). Only women can bear children.

But innate sex differences are far fewer than the fear greater number of gender

differences-- qualities ascribed to men or women within a given culture

and time. In another time and place, these characteristics might vary greatly

or even be the opposite. Inherited from medieval Spanish culture, since

colonial times Latin America has exhibited clear gender roles deemed appropriate

to men and to men. These roles are called machismo for men and marianismo

for women. The former simply means "maleness," while the latter takes as

its inspiration "Maria," Mary, the Mother of Jesus.

One of the foremost qualities of machismo is honor. A man's good

name, his reputation for doing the manly thing, demands firm defense of

one's honor. Even relatively mild challenges and rebukes should not be

tolerated. They besmirch one's honor. Among the most important elements

of upholding one's honor is to protect the women in one's care--be they

sister, mother, wife, or daughter. Women, thought of as physically and

mentally weaker then men, require male protection and guidance.

Machismo also requires domination. Men should dominate other men,

politically for example. Men should also show their machismo by dominating

women. Sexual conquest and progeny enhance a man's reputation. Such a drive

to dominate can pose a barrier to the give-and-take and "horse trading"

sometimes expected in politics. Intrasigence, an unwillingness to compromise,

is a more typically macho response then meeting an opponenet half way.

These models of male and female behavior reflect an "essentialist" assumption that men differ fundamentally from women. Essentialists believe, for example, that men are subject to biological drives, notably sex. Women, more spiritual less physical than men, did not share these basic biological drives. Thus is is understandable and expected if a man engages in extramartial sex or goes on drinking binges, but such behavior is unacceptable for a proper woman.

In sum, the caudillo, the virtual, commanding "man on horseback" is an appropriate role model for machismo. The obedient, highly moral and spiritual Mary, Mother of Jesus, is the guide for female behavior. As you

read in your texts, note how social class, race, economic necessity and other factors challenge and alter these gender role models. These models of male and female behavior reflect an "essentialist" assumption that men differ fundamentally from women. Essentialists believe, for example, that men are subject to biological drives, notably sex. Women, more spiritual less physical than men, did not share these basic biological drives. Thus is is understandable and expected if a man engages in extramartial sex or goes on drinking binges, but such behavior is unacceptable for a proper woman.

In sum, the caudillo, the virtual, commanding "man on horseback" is an appropriate role model for machismo. The obedient, highly moral and spiritual Mary, Mother of Jesus, is the guide for female behavior. As you

read in your texts, note how social class, race, economic necessity and other factors challenge and alter these gender role models.

END Men and Women

Methods of Elite Domination

As E. Bradford Burns showed in another book,

the 19th century brought increasing poverty and misery to the majority

of Latin Americans. In his book The Poverty of Progress (Univ. of

California Press, 1980), Burns vividly demonstrates the process. He concludes

the book by noting that the 19th century

"was not, after all, a century

of random conflicts, meaningless civil wars, and pervasive chaos, but one

in which those who favored modernization struggled with those loyal to

their folk societies and cultures. Finally, it provides one insight into

the constant and major enigma of Latin America: prevalent poverty in a

potentially wealthy region. The triumph of progress as defined by the elites

set the course for twentieth-century history. It bequeathed a legacy of

mass poverty and continued conflict."

As late readings will show, powerful links between past and present remain very strong in Latin America.

How did the elites successfully dominate the "folk," the rural masses?

During the colonial period, Spaniards used a variety of labor control mechanisms

to extract work from non-whites. African slaves worked on the vast sugar

and other tropical plantations. Indians, such as the Yaqui and Apache in

northern Mexico could also be enslaved thanks to the doctrine of the "just

war." Institutions including the mita, repartimiento, and encomienda controlled

native American labor. Landowners also created the condition of debt peonage

among workers by advancing them goods or money against future wages.

After independence most Spanish American nations abolished African

slavery. Brazil would not do so until 1888. Some of the repressive labor

institutions of colonial times disappeared. Debt peonage, however continued

into the twentieth century. In 1923 George McBride noted its continuance

as well as land monopoly by the few even after the Mexican Revolution of

1910-20.

By a system of advance payments, which the peons were totally unable to refund, the hacendados [landowners] were able to keep them permanently under finanaical obligations and hence to oblige them to remain upon the estates to which they belonged. . . . Furthermore, the peons are bound to the haciendas by mere necessity. Were they to leave, there is no no

unoccupied land upon which they might settle; and, if this were to be found,

they have neither tools, seeds, stock, nor savings with which to equip

farms of their own.

The ranching

elite of Argentina likewise used a variety of ingenious legal and political

mechanisms to control the gaucho and his labor. The bountiful herds

of wild cattle, horses, ostriches (rheas) and other game on the pampas

meant that a gaucho could subsist without working for someone else.

The elite steadily and surely eroded the gaucho's independence during

the 19th century. Note the variety of laws passed between 1820 and the

1850s. Note the codification of masses of repressive laws aimed at the

gaucho in the Rural Code of 1865. Other provinces in Argentina passed

similar codes. This welter of legislation effectively channeled the

gaucho in two directions. He had to labor as a peon (ranch worker) to

avoid being jailed as a vagrant, or he had to serve in the frontier

military and fight Indians. Both roles suited the landed elite very

well. The ranching

elite of Argentina likewise used a variety of ingenious legal and political

mechanisms to control the gaucho and his labor. The bountiful herds

of wild cattle, horses, ostriches (rheas) and other game on the pampas

meant that a gaucho could subsist without working for someone else.

The elite steadily and surely eroded the gaucho's independence during

the 19th century. Note the variety of laws passed between 1820 and the

1850s. Note the codification of masses of repressive laws aimed at the

gaucho in the Rural Code of 1865. Other provinces in Argentina passed

similar codes. This welter of legislation effectively channeled the

gaucho in two directions. He had to labor as a peon (ranch worker) to

avoid being jailed as a vagrant, or he had to serve in the frontier

military and fight Indians. Both roles suited the landed elite very

well.

Despite

their strenuous efforts, the elites could not competely control gaucho

behavior and movements. After all, a gaucho on horseback could flee

to the frontier and live beyond the reach of the law. Passing and enforcing

laws are two different things. For example, many Latin American nations

repeatedly outlawed a favorite blood sport, cockfighting. Gauchos would

wager heavily (well, as much as they could) on the outcome. Mexican

corridos (folksongs) celebrate the feats of the best fighting cocks.

Cockfighting is a popular activity in many Latino cultures, particularly

among men. Spectators gather to watch two cocks fight, usually until

one is wounded or dies. Often bets are placed on the birds. This painting

by Puerto Rican painter Rafael Trelles portrays a cockfight with extraordinary

vibrancy. The white cock almost ceases to be an animal and appears more

like a furious, disembodied force trying to annihilate the black cock. Despite

their strenuous efforts, the elites could not competely control gaucho

behavior and movements. After all, a gaucho on horseback could flee

to the frontier and live beyond the reach of the law. Passing and enforcing

laws are two different things. For example, many Latin American nations

repeatedly outlawed a favorite blood sport, cockfighting. Gauchos would

wager heavily (well, as much as they could) on the outcome. Mexican

corridos (folksongs) celebrate the feats of the best fighting cocks.

Cockfighting is a popular activity in many Latino cultures, particularly

among men. Spectators gather to watch two cocks fight, usually until

one is wounded or dies. Often bets are placed on the birds. This painting

by Puerto Rican painter Rafael Trelles portrays a cockfight with extraordinary

vibrancy. The white cock almost ceases to be an animal and appears more

like a furious, disembodied force trying to annihilate the black cock.

However, the elites managed to enforce enough of their laws to condemn gauchos to an increasingly marginalized and difficult existence. It is a truism in any country that not everyone is equal before the law. The poor,

landless, illiterate gaucho had little legal power or protection on his

side. The rich, landed elites--the estancieros--controlled the government

and made the laws to suit their own interests. Little wonder the gaucho's

world deteriorated throughout the century. José Hernández wrote eloquently

of the repression of the gaucho in his epic poem "Martin Fierro," published

in two parts during the 1870s. A few writer and politicians, like Hernández,

defended the masses against exploitation, but most, embued with the social

Darwinism of the time, had little interest in the worsening plight of the

poor.

END Elite Domination

The Poverty of Progress

Latin America

made tremendous material progress during the nineteenth century. In

the second half of the century, tens of thousands of miles of new railroad

lines criss-crossed the continent. Steam power replaced animal and human

labor at sugar mills and in other areas of the economy. Output of raw

materials, mostly agricultural and mineral, soared. Sugar, molasses,

and rum continued to pour forth from the Caribbean islands. After mid-century,

coffee fields spread across hillsides in Colombia, Brazil, El Salvador,

and other nations. Bolivia's mines produced tin while those in neighboring

Chile yielded copper. Argentina's rich pampas yielded cowhides, beef,

wool, mutton, and cereals. Across Europe one heard the phrase "Rich

as an Argentine" in recognition of the noveau riche landowners of that

nation.

Amidst all this progress for the landowning and merchant elites and their foreign counterparts, however, came increasing poverty for the rural masses. Speaking in the mid-1850s, a Mexican liberal named Ponciano Arriaga

pointed up the negative effects of continued land concentration, a problem that persists into the twentieth century. Latin America

made tremendous material progress during the nineteenth century. In

the second half of the century, tens of thousands of miles of new railroad

lines criss-crossed the continent. Steam power replaced animal and human

labor at sugar mills and in other areas of the economy. Output of raw

materials, mostly agricultural and mineral, soared. Sugar, molasses,

and rum continued to pour forth from the Caribbean islands. After mid-century,

coffee fields spread across hillsides in Colombia, Brazil, El Salvador,

and other nations. Bolivia's mines produced tin while those in neighboring

Chile yielded copper. Argentina's rich pampas yielded cowhides, beef,

wool, mutton, and cereals. Across Europe one heard the phrase "Rich

as an Argentine" in recognition of the noveau riche landowners of that

nation.

Amidst all this progress for the landowning and merchant elites and their foreign counterparts, however, came increasing poverty for the rural masses. Speaking in the mid-1850s, a Mexican liberal named Ponciano Arriaga

pointed up the negative effects of continued land concentration, a problem that persists into the twentieth century.

One of the most deeply rooted evils of our country.

. . is the monstrous division of landed property. While a few individuals

possess immense areas of uncultivated land that could support millions

of people, the great majority of Mexicans languish in a terrible poverty

and are denied property, homes, and work. Such a people cannot be free,

democratic, much less happy, no matter how many constitutions and laws

proclaim abstract rights and beautiful but impracticable theories--impracticable

by reason of an absurb economic system. This haunting problem of land concentration would be a major cause of the violent Mexican Revolution.

Technological change often spurs economic growth. As noted above, the application of steam power increased output at sugar mills. But technological change creates winners and losers. Gauchos of Argentina ranked among the losers. Wire fencing, for example, began to appear on the pampas of Argentina and neighboring Uruguay, by the 1850s. Ranchers could enclose pastures and keep cattle in one location. Thanks to fencing, the demand for gaucho herders dropped significantly. Fewer workers could tend the enclosed herds. Likewise railroads cut the demand for gaucho labor. Instead of using a large team of workers to drive herds over the vast pampas, ranchers could simply drive the animals to a nearby rail head. Steam-powered sheep shearing machines replaced hand clippers. One worker could shear many more animals thus reducing demand for sheep shearers. In countless ways, changes in technology displaced rural workers and cut the demand for their labor.

An increasing focus on cash crop exports also worked to the detriment of the rural masses. Landowners devoted increasing amounts of acreage to export crops, such as sugar cane, cereals, coffee, cotton, tobacco, and other agricultural produce. This left less land--and less fertile land--for local food production. Many nations, including Mexico and Bolivia, began to import food they had once raised themselves.

[Flag of Brazil] An editiorial in the Brazilian newspaper, "Diario

de Pernambuco" (Recife, March 24, 1856) discussed a related land

problem--fallow lands held by the elite and not productively employed.

[Flag of Brazil] An editiorial in the Brazilian newspaper, "Diario

de Pernambuco" (Recife, March 24, 1856) discussed a related land

problem--fallow lands held by the elite and not productively employed.

Here, as the growing of sugarcane demands, a certain amount of land, which cannot be found everywhere, is devoted to the cultivation of the cane. Other parts of the plantation are dedicted to the woods that are necessary for sugar production, the pastures for the care of the oxen, and the gardens for the planting of manioc, indispensable for the feeding of the slaves. But still a major part of the plantation possesses vast extensions of uncultivated land that would be especially well suited for the small farmer and which, if cultivated, would be sufficint to furnish abundantly flour, corn, beans, etc., to all the population of the province. . . . The proprieters refuse to sell these lands or even to rent them. The elite's stranglehold on land spelled their continued wealth but left most of the rural poor in adject poverty.

Increased agricultural production spurred the demand for labor in many parts of Latin America, but probably nowhere more dramatically than in Argentina. Beginning in the 1880s, ranchers there moved from the production of native (criollo) cattle, good for hides and jerked meat, to raising hybrid animals for the chilled beef trade. These new cattle breeds would not feed on the native grasses, so ranchers needed to grow alfalfa. Gauchos, however, refused to do lowly foot work. Argentina began advertising for workers in Europe and found them. Hundreds of thousands of migrant farm workers (called golondrinas, swallows) crossed the Atlantic Ocean to plant and harvest crops on the pampas. Most worked only during the busy seasons then returned to Italy, Spain, or another homeland.

Those farm workers who stayed in temporary shacks as tenants. They would grow corn or wheat or another cereal for three to five years, earning a portion of the harvest. Then they would plant alfalfa for the landowner and leave. Cattle would eat the alfalfa, and the migrant farm workers would move to another plot somewhere and begin the process anew. Needless to say, few immigrants escaped this gypsy-like existence. The estancieros would not sell their lands, thereby closing off upward mobility to most immigrants. [For a complete history of these immigrants, read James R. Scobie, Revolution on the Pampas: A Social History of Argentine Wheat, 1860-1910, Univ. of Texas Press, 1964).

Some native-born Latin Americans resented and resisted the influx of foreigners. Nativist literature extolled the virtues of those born in Latin America and attacked immigrants. Some gauchos identified immigrants with unwanted changes-- building fences, farming, running railroads -- and also vented their anti-foreign sentiments. The horrifying attack on immigrants launched from Tandil in 1872 is the most graphic example of the gaucho's anti-foreign sentiments. In Argentina, the term "pampa gringa," the foreign plains, arose to describe the changed landscape of the late nineteenth century. Gauchos and many others of the rural poor had lost most ground, literally and figuratively, during the century.

Alas the region, the naive faith in exporting commodities as a means of developing national economies remains. And as in the 19th century, commodity exports remains a losing proposition for Latin America. Note the recent analysis of "COMMODITY PROBLEMS" by the publication Latin American Economy & Business (April 2002).

Commodity producers are still suffering from depressed prices. Even the surge in oil prices in recent weeks cannot disguise the fact that ,in real terms, the prices of all the major commodities are lower than they were in 1980. Metal prices are a long way shy of the levels they reached in the early 1980s. In nominal terms, gold is at around half the levels recorded in the early 1980s. Copper, tin and silver are also considerably lower.

More worrying for policymakers is the sustained weakness of agricultural prices. This is bad news for two reasons. The first is that weak commodity prices make it much more difficult to wean farmers away from subsistence farming. Cash crops, theoretically at least, contribute to economic development by demanding (and to a large extent paying for) infrastructure. Cash crops also stimulate ancillary industries such as packaging and transport. From a Latin American point of view, the second problem posed by weak commodity prices is that the whole theory of crop substitution as a way of suppressing the drug trade in undermined.

Stats. It has always been hard to encourage primary producers of coca and opium poppies to switch to other crops. Few comparable crops provide the four harvests that the coca bush provides. Tea bushes would, but the price of tea has been sliding and is now as low as coffee. And coffee prices are horribly low. A recent study by the World Bank found that coffee prices had fallen by 84% in real terms between 1980 and 2002.

Other agricultural commodities were also struggling to provide the return they offered a generation ago. Maize prices were down by 36% and sugar prices were down by 76%. One of the biggest cautionary tales is of cotton. In 1980, cotton was selling for US$2.62 a kilo. Now it is selling for US$1.10 a kilo.

Substitution. The problem posed by the weak coffee price to small producers in Latin America is well known. In Colombia and Central America, governments are having to support the coffee industry to preserve agricultural and social rhythms and their contribution to social harmony.

In the drug producing areas, weak commodity prices make efforts at crop substitution even more forlorn. In Bolivia, the government seems to have all but given up on substitution, preferring repeated eradication. In Colombia, almost 10% of the US$1.3bn in annual aid from the US was earmarked for crop substitution, but only US$6m has been committed.

Nobody really knows how much coca is being grown in Colombia and how much has been destroyed. The Colombian government claims that over 1,000 hectares have been destroyed since January 2002. This is, it says, close to 20% of the 5,677 ha it will eradicate this year. The CIA reckons that coca production in Colombia increased by 30% last year, despite the spraying and fumigation of 85,000 ha of coca. The Colombian government itself reckons that 144,600 ha are devoted to coca production.

Drugs? Although the World Bank does not go into the issue, it is more than likely that the price of illegal cash crops, such as opium poppies, coca and marihuana, has fallen in line with other commodity prices. It seems that the street price of drugs in the US is, if anything, continuing to fall. The general rule is that 90% of the money made from illegal drugs is made in getting the stuff from the US border to the street. The cost of getting it from the producer to the US border is about 10% of the retail price of the drug.

Removing producer subsidies in the industrialized world may help push up the price of some agricultural commodities (such as meat and dairy products, sugar and some grains). Industrialized countries could also probably boost the price of some tropical commodities such as coffee, by encouraging more processing to take place in the producing countries.

END Poverty of Progress

Frontier Myth versus Frontier History

Myth has always been more powerful, pervasive, and alluring than histortical reality. The Merriam Webster Online Dictionary tells us that myth, from the Greek word mythos, is a “traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon.” In the American West, for example, we have many such tales, such as the significance of the white buffalo and the story of Aztlán, mythical southwestern homeland of the Aztecs.

A myth may also be “a popular belief or tradition that has grown up around something or someone; especially one embodying the ideals and institutions of a society or segment of society.” Again, the American West is rife with such myths, most notably those relating to putative frontier virtues, such as rugged individualism, democracy, and opportunity. Finally a myth might be “a person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence”-- figures such as Pecos Bill and Bigfoot, for example.

A related term, “mythical,” dates in English from 1669, “based on or described in a myth especially as contrasted with history.” In some cases, such as mountain man Jeremiah "Liver-eating" Johnson, an actual historical figure becomes mythologized. But mythical can also mean “having qualities suitable to myth, legendary,” famous people from "Buffalo Bill" Cody to Gene Autry--flesh-and-blood humans, whose lives and careers catapulted them into the realm of the legendary.

Many figures and eras of history are shrouded in myth. Since ancient

times, people have made up stories to help them explain and understand

the world. Thus we get panetheons of gods presiding over natural processes:

Thor, the Norse god of Thunder, smashing down his giant hammer. Folklore

produces mythic beings capable of astounding feats: Paul Bunyan and his

blue ox Babe, Peco Bill. Societies also create mythical heroes to serve

as role models for their citizens to emulate. In most cases, myths tell

us more more about the aspirations and values of a society than about the

real historical events or persons who become mythologized. Politicians and writers in Argentina, for example, created a mythical gaucho to hold up as a role model for what they considered to be politically dangerous and unruly recent immigrants.

The Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, has a wonderful

collection of artifacts representing both cowboy history and mythology.

Let me quote from a card that the Center distributes on the nature of history

and myth.

History is not just a time line, since a time line takes events

out of context. History is also our interpretation of the past. It is not

just who did what and where. It is also why and how. Why did people think

and act the way they did? How did they reach their decisions? What were

the consequences? A myth is a story that helps us to explain our world.

The story may be mostly true, and it helps us to understand what kind of

people we are. For example, the life stories of George Washington and

Abraham Lincoln are important American myths. They provide images to live

up to. They define ideal American poltiical leaders. The cowboy, and stories

about taming the West, are also part of American myth. In our image of

the cowboy, he has what we like to think are truly American qualities.

Several varieties of myth have developed out of frontiers in North and South America and in Australia.

First, we have the myth of the Golden Frontier of treasure, abundance, and opportunity. Alluring tales of treasure greeted the earliest Spanish and Portuguese explorers in this hemisphere. Beginning with Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, we have tales of a land "abounding in gold and silver, with (seven) great cities whose houses were many stories high, whose streets were lined with silversmiths' shops, and whose doors were inlaid with turquoise." Coronado, after traveling for months in the wilderness, reached the so-called Seven Cities of Gold in the land that he named Cibola. Real, as opposed to imagined gold strikes would lure immigrants westward for centuries. [The painting, at Cañon del Muerte, Arizona, shows an early indigenous reaction to the coming of Spanish conquistadores, with their lances, and the priest, black poncho with the cross on it.]

In South America, the wealth of the Chibchas or Muiscas in the Andes created a vision of "El Dorado," the gilded one. The mass of golden artifacts at Gold Museum in Bogotá, Colombia illustrates that this myth of great golden riches has some very tangible roots. Indeed by 1600, New Granada had exported more than 4 million ounces of gold. Output eventually totaled some 30 million ounces. In contrast, Portuguese explorers would search in vain for nearly two centuries for the precious metal. Finally, frontier slave hunters and explorers called bandeirantes discovered riches in Minas Gerais in 1695, and Brazil's first gold rush was on.

Second, we have the myth of the frontier as a Desert of Barbarism and Emptiness. Oddly, this parallel negative myth arose along with the myths of gold, garden, and riches. Stephen H. Long, who surveyed a portion of the Louisiana Purchase in 1819, labeled these western territories the "Great American Desert." Walter Prescott Webb created an uproar in the 1950s by reaffirming this view of much of the inland West as a desert.

In South America, Brazil's Amazon and Argentina's Patagonia remained largely uninhabited by Europeans until the 20th century. And in Australia, with two-thirds of its land area technically desert, we see no Horace Greeley urging people to the frontier. Instead we have dreadful warnings of children lost forever in the outback.

In the Americas, great open spaces set people free and promised new opportunities, while in Australia, open space functioned as a restrictive prison. Any attempt to escape into the outback's forbidding terrain invited hardship, starvation, and death. Nonetheless, over the past 200 years, the white urge to conquer this harsh landscape laid the foundation for Australia's nation building. It also set in motion an inevitable clash with the continent's Aborigines, who were spiritually bonded and well adapted to the vast inland deserts.

Like the landscape, the inhabitants of these frontiers generated mostly negative imagery. Viewed as savages and barbarians, the colored native populations generated fear and loathing. Even after the penetration of whites, frontier inhabitants remained fearful specters, uncivilized, dangerous. Gauchos of Argentina and llaneros of Venezuela and Colombia-- mixed blood cowboys -- were viewed as little better than the natives. Argentina's Domingo F. Sarmiento provided the best known paradigm of these dangerous frontiersman with his 1845 book Civilization and Barbarism. "Indian country," or, in Australia, "aborigine country," did not invite anything other than conquest.

Third, the Myth of the Frontier as the Key to Future Greatness has arisen in many countries. As historian Patricia N. Limerick has acknowledged, the contradictions and hollowness of past frontier myths have not dulled the attraction of frontier metaphor as THE place of future opportunity. Brazil's push to the West took physical form in the 1960s with the creation of the new national capital of Brasilia on the edge of the Amazonian wilderness. Today gold miners or garimpeiros, most working illegally, have created a new Amazonian gold rush.

Hoping to emulate Brasilia's success, Argentina briefly renamed its currency the austral to point national energy south toward its vast, still sparsely settled Patagonian frontier. In similar fashion, Venezuela pins its hopes on its remote inland Orinoco River Basin. In each case, the frontier is seen as a land of unlimited opportunity and resources, the key to future national greatness. Thus myths of the frontier as well as mythologized figures like the gaucho continue to influence cultures around the globe. First, we have the myth of the Golden Frontier of treasure, abundance, and opportunity. Alluring tales of treasure greeted the earliest Spanish and Portuguese explorers in this hemisphere. Beginning with Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, we have tales of a land "abounding in gold and silver, with (seven) great cities whose houses were many stories high, whose streets were lined with silversmiths' shops, and whose doors were inlaid with turquoise." Coronado, after traveling for months in the wilderness, reached the so-called Seven Cities of Gold in the land that he named Cibola. Real, as opposed to imagined gold strikes would lure immigrants westward for centuries. [The painting, at Cañon del Muerte, Arizona, shows an early indigenous reaction to the coming of Spanish conquistadores, with their lances, and the priest, black poncho with the cross on it.]

In South America, the wealth of the Chibchas or Muiscas in the Andes created a vision of "El Dorado," the gilded one. The mass of golden artifacts at Gold Museum in Bogotá, Colombia illustrates that this myth of great golden riches has some very tangible roots. Indeed by 1600, New Granada had exported more than 4 million ounces of gold. Output eventually totaled some 30 million ounces. In contrast, Portuguese explorers would search in vain for nearly two centuries for the precious metal. Finally, frontier slave hunters and explorers called bandeirantes discovered riches in Minas Gerais in 1695, and Brazil's first gold rush was on.

Second, we have the myth of the frontier as a Desert of Barbarism and Emptiness. Oddly, this parallel negative myth arose along with the myths of gold, garden, and riches. Stephen H. Long, who surveyed a portion of the Louisiana Purchase in 1819, labeled these western territories the "Great American Desert." Walter Prescott Webb created an uproar in the 1950s by reaffirming this view of much of the inland West as a desert.

In South America, Brazil's Amazon and Argentina's Patagonia remained largely uninhabited by Europeans until the 20th century. And in Australia, with two-thirds of its land area technically desert, we see no Horace Greeley urging people to the frontier. Instead we have dreadful warnings of children lost forever in the outback.

In the Americas, great open spaces set people free and promised new opportunities, while in Australia, open space functioned as a restrictive prison. Any attempt to escape into the outback's forbidding terrain invited hardship, starvation, and death. Nonetheless, over the past 200 years, the white urge to conquer this harsh landscape laid the foundation for Australia's nation building. It also set in motion an inevitable clash with the continent's Aborigines, who were spiritually bonded and well adapted to the vast inland deserts.

Like the landscape, the inhabitants of these frontiers generated mostly negative imagery. Viewed as savages and barbarians, the colored native populations generated fear and loathing. Even after the penetration of whites, frontier inhabitants remained fearful specters, uncivilized, dangerous. Gauchos of Argentina and llaneros of Venezuela and Colombia-- mixed blood cowboys -- were viewed as little better than the natives. Argentina's Domingo F. Sarmiento provided the best known paradigm of these dangerous frontiersman with his 1845 book Civilization and Barbarism. "Indian country," or, in Australia, "aborigine country," did not invite anything other than conquest.

Third, the Myth of the Frontier as the Key to Future Greatness has arisen in many countries. As historian Patricia N. Limerick has acknowledged, the contradictions and hollowness of past frontier myths have not dulled the attraction of frontier metaphor as THE place of future opportunity. Brazil's push to the West took physical form in the 1960s with the creation of the new national capital of Brasilia on the edge of the Amazonian wilderness. Today gold miners or garimpeiros, most working illegally, have created a new Amazonian gold rush.

Hoping to emulate Brasilia's success, Argentina briefly renamed its currency the austral to point national energy south toward its vast, still sparsely settled Patagonian frontier. In similar fashion, Venezuela pins its hopes on its remote inland Orinoco River Basin. In each case, the frontier is seen as a land of unlimited opportunity and resources, the key to future national greatness. Thus myths of the frontier as well as mythologized figures like the gaucho continue to influence cultures around the globe.

Probably moreso than any other frontier figure, cowboys have become mythical

beings in many countries. The cowboy of the American West, with his broad-brimmed hat, blue jeans, high boots, and horse, is immediately recognizable anywhere in the world. The figures conjures images of rugged individualism, mastery over nature, truthfulness, and hard work. Politicians, from Theodore Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson and Ronald Reagan cultivated cowboy imagery to sell their political ideas. Likewise advertisers have used cowboys to hype everything from cereals and spools of thread to beer, computers, and pickup trucks. Probably moreso than any other frontier figure, cowboys have become mythical

beings in many countries. The cowboy of the American West, with his broad-brimmed hat, blue jeans, high boots, and horse, is immediately recognizable anywhere in the world. The figures conjures images of rugged individualism, mastery over nature, truthfulness, and hard work. Politicians, from Theodore Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson and Ronald Reagan cultivated cowboy imagery to sell their political ideas. Likewise advertisers have used cowboys to hype everything from cereals and spools of thread to beer, computers, and pickup trucks.

By

using a comparative approach to history, we can investigate and attempt

to explain the similarities and differences between different social

groups. For instance, why do similar conflicts arise in frontier regions?

By comparing events in different times and places, we can better identify

the effects of wide range of variables, such as culture, social class,

nature of the economy, and so forth. Peruse this

Comparative

Frontiers: A Working Bibliography for a look at the range of

comparative literature available. Most of the sources come from my book,

Comparing Cowboys and Frontiers (University of Oklahoma Press,

1997, paperback summer 2001). The book treats frontiers and frontier

types, including cowboys, throughout North and South America. For example,

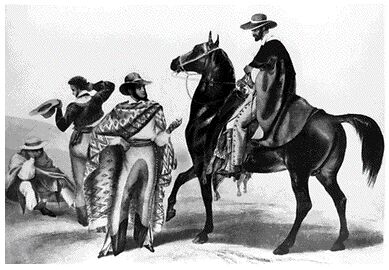

the vaquero or cowboy, shown in this illustration from about 1800, worked

on Mexican haciendas (ranches) just as the gaucho did in Argentina.

As in Argentina, most vaqueros were Indians or of mixed blood.

Like the North American cowboy, the gaucho of Argentina has reached mythic proportions. As with riders elsewhere, sharply conflicting images have been associated with this cowboy of the pampas. Novelists, travelers, politicians, and poets have all assigned different qualities--good and bad-- to the gaucho. Overall the gaucho won the battle of public opinion in the nation. Today, in contrast to the past century, the gaucho is generally viewed in a favorable light. Some mythical characteristics fit accurately with the real, historical gaucho, but many do not. By

using a comparative approach to history, we can investigate and attempt

to explain the similarities and differences between different social

groups. For instance, why do similar conflicts arise in frontier regions?

By comparing events in different times and places, we can better identify

the effects of wide range of variables, such as culture, social class,

nature of the economy, and so forth. Peruse this

Comparative

Frontiers: A Working Bibliography for a look at the range of

comparative literature available. Most of the sources come from my book,

Comparing Cowboys and Frontiers (University of Oklahoma Press,

1997, paperback summer 2001). The book treats frontiers and frontier

types, including cowboys, throughout North and South America. For example,

the vaquero or cowboy, shown in this illustration from about 1800, worked

on Mexican haciendas (ranches) just as the gaucho did in Argentina.

As in Argentina, most vaqueros were Indians or of mixed blood.

Like the North American cowboy, the gaucho of Argentina has reached mythic proportions. As with riders elsewhere, sharply conflicting images have been associated with this cowboy of the pampas. Novelists, travelers, politicians, and poets have all assigned different qualities--good and bad-- to the gaucho. Overall the gaucho won the battle of public opinion in the nation. Today, in contrast to the past century, the gaucho is generally viewed in a favorable light. Some mythical characteristics fit accurately with the real, historical gaucho, but many do not.

Leaving aside myth for a moment, what about the gaucho of today? Here's a report from 1995 on gaucho life in Argentina. As Carl Honore reports, life hasn't gotten any better: "GOODBYE, GAUCHOS: COWBOYS ARE RIDING INTO THE SUNSET IN ARGENTINA" (St. Louis Post-Dispatch 03-12-1995, pp 07A. Reprinted from the London Observer).

Across the pampas of Argentina, gauchos, the South American cowboys of legend, are dying out. Still, with a face as dark and leathery as rawhide and a horseman' s swagger, Pedro Zarza is every inch a gaucho. But these days, his hours herding cattle on La Pelada, a ranch 375 miles north of Buenos Aires, have been cut back. His boss has laid off other gauchos and sold off one-fifth of the estate.

Zarza's forebears roamed freely across the unclaimed pampas, hunting cattle, sleeping by campfires and drinking and gambling in rustic saloons. When land was parceled off in the mid-19th century, the gaucho was forced to settle, but he still retained much of the rugged dignity and free spirit that made him an Argentine icon.

Today Zarza has to take tourists for horseback rides to pull in more cash. He counts himself fortunate that his boss hasn't asked him to entertain the tourists with campfire songs. Some ranchers even hire fake gauchos to round out the spectacle with folk dances of dubious origin. Zarza shakes his head. "Will the good times ever return?" he asks.

On the surface, ranches such as Los Yngleses appear as splendid as ever. Lined with ancient eucalyptus trees, the driveway winds past picket fences and a swimming pool and up to a gleaming white homestead. Flowers bloom along the fringes of a manicured lawn, and cattle graze on the surrounding plains. It looks like a tableau of the prosperous Argentine pampas.

Hunched over afternoon tea in the drawing room, John Boote tears the tableau to pieces. The ranch, founded by his Scottish ancestor 170 years ago, hasn't yielded a peso of profit since 1991. "We estancieros (ranchers) are the new poor of Argentina." Figuratively, Los Yngleses, 200 miles south of Buenos Aires, is on its knees. The family car and farm machinery are relics, and the fencing and canals are in disrepair. Half the cabins reserved for gauchos stand empty.

Owning land in Argentina was once a license to print money. The pampas made Argentina fabulously wealthy earlier in this century, and landowners, many of British stock, were the backbone of the local elite. Today, although some still enjoy the high life, most have only memories of the European tours and posh clubs, the luxurious apartments in Buenos Aires and holiday homes on the coast. "Nobody dreams of being an estanciero anymore," Boote says. "Our children don't want to take over the ranch, and I'm almost past caring what happens next."

Why are the pampas so humbled? Falling agricultural prices and inheritance laws that break up estates have done much damage. An economic overhaul has recently pushed costs through the roof. The ranchers also are reeling from a stab in the back. Health concerns have cut the average intake of red meat in Argentina by one-fifth since the 1970s.

Even presidential plugs for steak dinners and voluminous research suggesting that local beef is low in cholesterol fail to dent the new fat-phobia. Argentines still eat far more beef than most other folk, but other meats are gaining space on the nation's grills, and "restaurante vegetariano" is spreading across the urban landscape. But the "for sale" signs hung throughout the pampas are not just an epitaph for the traditional estanciero. As their traditional work gradually evaporates, gauchos are swapping their baggy bombacha (trousers) and lifestyle for jeans and odd jobs in the cities.

Myths do not arise out of thin air; someone creates them. Folk myths usually arise from the oral traditions of preliterate societies. However, many of the myths about gauchos came from urban, literate elite intellectual--not from folk tradition. Why did the elites of Argentina create myths about the gaucho? Examine the gaucho as depicted by Sarmiento, Hernández, Lugones, Rojas, Quesada, Gutiérrez, Lynch, and others. How are their depictions similar to and different from the men who actually rode the pampas as flesh-and-blood ranch hands?

END Frontier Myth and Reality

|

Let's start with a Gaucho Photo Gallery for a quick look at this fascinating historical figure. Although most of the images are contemporary, you'll see that much gaucho equipment and dress remains largely unchanged since the 19th century. The Spanish conquistadores and their Portuguese counterparts brought many elements of European culture to Latin America. On Columbus's second voyage in 1493-94, for example, he brought horses and cattle to the Caribbean. Extending out from the Caribbean, livestock raising became a major economic activity in many grasslands regions of North and South America. In northern Mexico and California, Roman Catholic missions played an important role in speading ranching and in teaching Indians to work as cowboys. Horsemen of the Americas originally hunted vast herds of wild cattle and horses for their hides. These horsemen developed unique equestrian subcultures that blended indigenous and European elements.

[The map to the right shows the pampas, the vast, grassy plain where the gauchos of Argentina and Uruguay, as well as the similar gauchos of southern Brazil, rode. Compare the varieties of Brazilian cowboys described in 1902 by Brazilian writer Euclides da Cunha.

At night we stopped at a pulperia, or drinking-shop. During the evening a great number of Gauchos came in to drink spirits and smoke cigars: their appearance is very striking; they are generally tall and handsome, but with a proud and dissolute expression of countenance. They frequently wear their mustaches and long black hair curling down their backs. With their brightly-coloured garments, great spurs clanking about their heels, and knives stuck as daggers (and often so used) at their waists, they look a very different race of men from what might be expected from their name of Gauchos, or simple countrymen. Their politeness is excessive: they never drink their spirits without expecting you to taste it; but whilst making their exceedingly graceful bow, they seem quite as ready, if occasion offered, to cut your throat. [from "Gauchos" in The Cowboy Encyclopedia and Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier]By the early 1800s, ranchers began processing dried meat for export to Brazil and Cuba. This jerky (charqui) made cattle more valuable and further increased the rancher desire to control land, water, animals, and grass on the pampa. Gauchos did not share the rancher's private property ethic, and conflicts arose. Over time, gauchos had to change their way of life from wild cattle hunting on the open range to branding the cattle of the land owners who oppressed them. Indeed, as the late distinguished historian E. Bradford Burns has written, elite-mass confict forms a major motif in 19th-century Latin American history. This conflict resulted in "the victory of the European-oriented ruling elites over the Latitn American folk with their community values." (Burns, The Poverty of Progress, Univ. of California Press, 1980, p. 1).

At night we stopped at a pulperia, or drinking-shop. During the evening a great number of Gauchos came in to drink spirits and smoke cigars: their appearance is very striking; they are generally tall and handsome, but with a proud and dissolute expression of countenance. They frequently wear their mustaches and long black hair curling down their backs. With their brightly-coloured garments, great spurs clanking about their heels, and knives stuck as daggers (and often so used) at their waists, they look a very different race of men from what might be expected from their name of Gauchos, or simple countrymen. Their politeness is excessive: they never drink their spirits without expecting you to taste it; but whilst making their exceedingly graceful bow, they seem quite as ready, if occasion offered, to cut your throat. [from "Gauchos" in The Cowboy Encyclopedia and Gauchos and the Vanishing Frontier]By the early 1800s, ranchers began processing dried meat for export to Brazil and Cuba. This jerky (charqui) made cattle more valuable and further increased the rancher desire to control land, water, animals, and grass on the pampa. Gauchos did not share the rancher's private property ethic, and conflicts arose. Over time, gauchos had to change their way of life from wild cattle hunting on the open range to branding the cattle of the land owners who oppressed them. Indeed, as the late distinguished historian E. Bradford Burns has written, elite-mass confict forms a major motif in 19th-century Latin American history. This conflict resulted in "the victory of the European-oriented ruling elites over the Latitn American folk with their community values." (Burns, The Poverty of Progress, Univ. of California Press, 1980, p. 1).

These models of male and female behavior reflect an "essentialist" assumption that men differ fundamentally from women. Essentialists believe, for example, that men are subject to biological drives, notably sex. Women, more spiritual less physical than men, did not share these basic biological drives. Thus is is understandable and expected if a man engages in extramartial sex or goes on drinking binges, but such behavior is unacceptable for a proper woman.

The ranching elite of Argentina likewise used a variety of ingenious legal and political mechanisms to control the gaucho and his labor. The bountiful herds of wild cattle, horses, ostriches (rheas) and other game on the pampas meant that a gaucho could subsist without working for someone else. The elite steadily and surely eroded the gaucho's independence during the 19th century. Note the variety of laws passed between 1820 and the 1850s. Note the codification of masses of repressive laws aimed at the gaucho in the Rural Code of 1865. Other provinces in Argentina passed similar codes. This welter of legislation effectively channeled the gaucho in two directions. He had to labor as a peon (ranch worker) to avoid being jailed as a vagrant, or he had to serve in the frontier military and fight Indians. Both roles suited the landed elite very well.

Despite their strenuous efforts, the elites could not competely control gaucho behavior and movements. After all, a gaucho on horseback could flee to the frontier and live beyond the reach of the law. Passing and enforcing laws are two different things. For example, many Latin American nations repeatedly outlawed a favorite blood sport, cockfighting. Gauchos would wager heavily (well, as much as they could) on the outcome. Mexican corridos (folksongs) celebrate the feats of the best fighting cocks. Cockfighting is a popular activity in many Latino cultures, particularly among men. Spectators gather to watch two cocks fight, usually until one is wounded or dies. Often bets are placed on the birds. This painting by Puerto Rican painter Rafael Trelles portrays a cockfight with extraordinary vibrancy. The white cock almost ceases to be an animal and appears more like a furious, disembodied force trying to annihilate the black cock.

Latin America made tremendous material progress during the nineteenth century. In the second half of the century, tens of thousands of miles of new railroad lines criss-crossed the continent. Steam power replaced animal and human labor at sugar mills and in other areas of the economy. Output of raw materials, mostly agricultural and mineral, soared. Sugar, molasses, and rum continued to pour forth from the Caribbean islands. After mid-century, coffee fields spread across hillsides in Colombia, Brazil, El Salvador, and other nations. Bolivia's mines produced tin while those in neighboring Chile yielded copper. Argentina's rich pampas yielded cowhides, beef, wool, mutton, and cereals. Across Europe one heard the phrase "Rich as an Argentine" in recognition of the noveau riche landowners of that nation.

[Flag of Brazil] An editiorial in the Brazilian newspaper, "Diario de Pernambuco" (Recife, March 24, 1856) discussed a related land problem--fallow lands held by the elite and not productively employed.

Here, as the growing of sugarcane demands, a certain amount of land, which cannot be found everywhere, is devoted to the cultivation of the cane. Other parts of the plantation are dedicted to the woods that are necessary for sugar production, the pastures for the care of the oxen, and the gardens for the planting of manioc, indispensable for the feeding of the slaves. But still a major part of the plantation possesses vast extensions of uncultivated land that would be especially well suited for the small farmer and which, if cultivated, would be sufficint to furnish abundantly flour, corn, beans, etc., to all the population of the province. . . . The proprieters refuse to sell these lands or even to rent them.The elite's stranglehold on land spelled their continued wealth but left most of the rural poor in adject poverty.First, we have the myth of the Golden Frontier of treasure, abundance, and opportunity. Alluring tales of treasure greeted the earliest Spanish and Portuguese explorers in this hemisphere. Beginning with Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, we have tales of a land "abounding in gold and silver, with (seven) great cities whose houses were many stories high, whose streets were lined with silversmiths' shops, and whose doors were inlaid with turquoise." Coronado, after traveling for months in the wilderness, reached the so-called Seven Cities of Gold in the land that he named Cibola. Real, as opposed to imagined gold strikes would lure immigrants westward for centuries. [The painting, at Cañon del Muerte, Arizona, shows an early indigenous reaction to the coming of Spanish conquistadores, with their lances, and the priest, black poncho with the cross on it.]

Probably moreso than any other frontier figure, cowboys have become mythical beings in many countries. The cowboy of the American West, with his broad-brimmed hat, blue jeans, high boots, and horse, is immediately recognizable anywhere in the world. The figures conjures images of rugged individualism, mastery over nature, truthfulness, and hard work. Politicians, from Theodore Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson and Ronald Reagan cultivated cowboy imagery to sell their political ideas. Likewise advertisers have used cowboys to hype everything from cereals and spools of thread to beer, computers, and pickup trucks.

By using a comparative approach to history, we can investigate and attempt to explain the similarities and differences between different social groups. For instance, why do similar conflicts arise in frontier regions? By comparing events in different times and places, we can better identify the effects of wide range of variables, such as culture, social class, nature of the economy, and so forth. Peruse this Comparative Frontiers: A Working Bibliography for a look at the range of comparative literature available. Most of the sources come from my book, Comparing Cowboys and Frontiers (University of Oklahoma Press, 1997, paperback summer 2001). The book treats frontiers and frontier types, including cowboys, throughout North and South America. For example, the vaquero or cowboy, shown in this illustration from about 1800, worked on Mexican haciendas (ranches) just as the gaucho did in Argentina. As in Argentina, most vaqueros were Indians or of mixed blood.